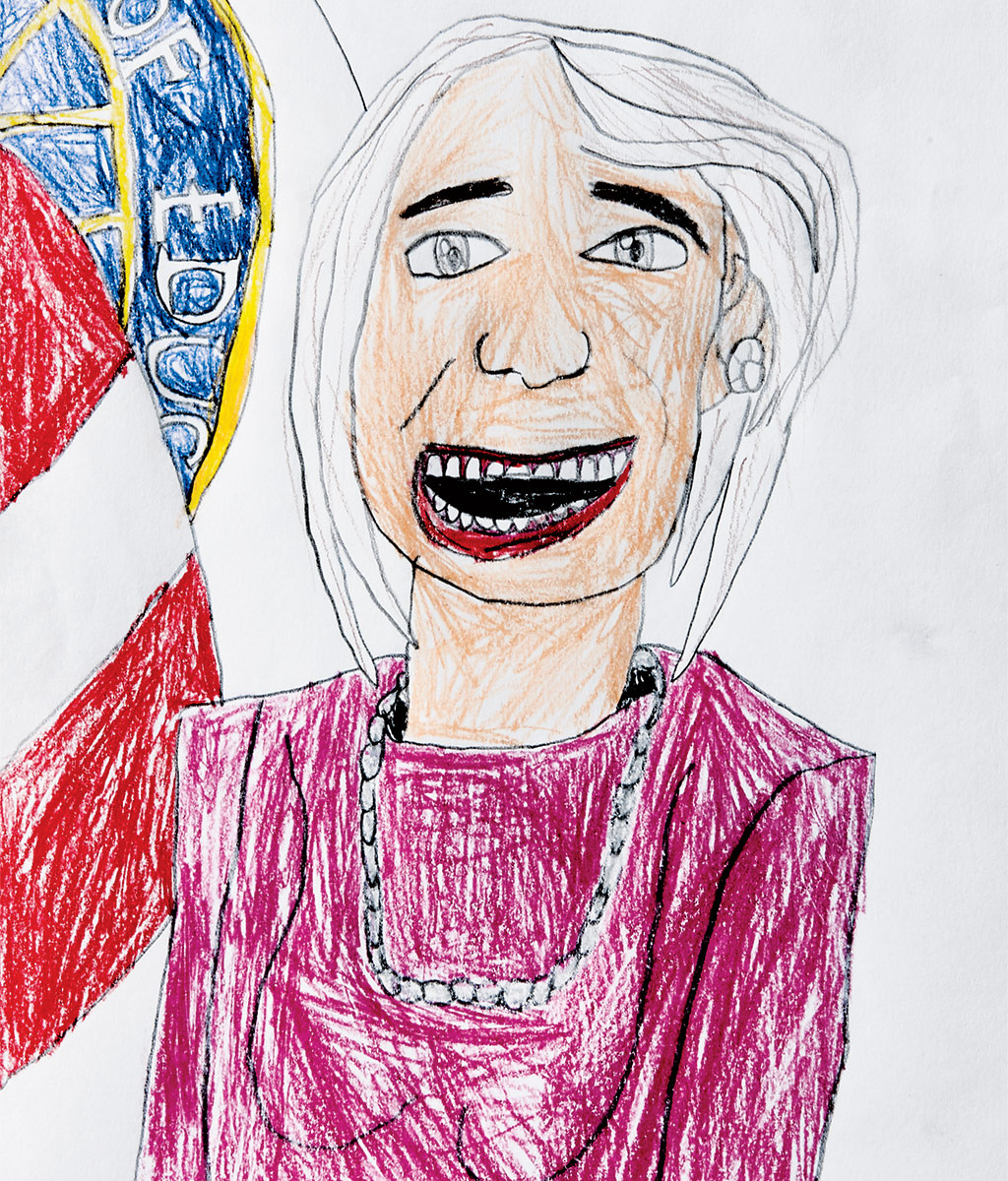

Betsy DeVos used to have more friends. Way back in 2016, a coalition of reputable, fair-minded education reformers — some of them Democrats — got together to vouch for her. Sure, she was inexperienced in the policy realm. Also, an outsider to Washington. Also, naïve to the demands of living under the internet’s ever-watchful eye. Still, it seemed to these surrogates that in choosing a secretary of Education, the president-elect might have done a lot worse. DeVos, a Michigan billionaire and Republican stalwart, had been pouring her energies and her fortune into education for years. Besides, she had signaled a strong distaste for Trump. She attended the convention as a delegate for John Kasich, leading these hopefuls to think that she might approach her new post with the venerable reasonableness of her party’s middle branch. “She is the Establishment. She reeks of Establishment,” says someone who used to work for her.

Betsy DeVos used to have more friends. Way back in 2016, a coalition of reputable, fair-minded education reformers — some of them Democrats — got together to vouch for her. Sure, she was inexperienced in the policy realm. Also, an outsider to Washington. Also, naïve to the demands of living under the internet’s ever-watchful eye. Still, it seemed to these surrogates that in choosing a secretary of Education, the president-elect might have done a lot worse. DeVos, a Michigan billionaire and Republican stalwart, had been pouring her energies and her fortune into education for years. Besides, she had signaled a strong distaste for Trump. She attended the convention as a delegate for John Kasich, leading these hopefuls to think that she might approach her new post with the venerable reasonableness of her party’s middle branch. “She is the Establishment. She reeks of Establishment,” says someone who used to work for her.

Jeb Bush liked her. So did his mother. So did Campbell Brown, the TV anchor turned education activist. On Twitter, Eva Moskowitz, the prominent charter-schools founder, said she was “thrilled to see such a passionate leader selected for such an important role.” True, these were people who had taken her money and sat on her boards (or she on theirs), but they still staked their optimism on her prospective success.

Now these cheerleaders have gone quiet, evading the opportunity to offer further praise. Campbell Brown cites a conflict with her new employer, Facebook. Jeb Bush won’t come to the phone. Teresa Weatherall Neal, the superintendent of schools in Grand Rapids, Michigan, who in November said she was “excited for the children across the nation” at the thought of DeVos’s leadership, declines to comment. Richard Mouw, a prominent Evangelical intellectual, met DeVos through church and was more than happy to write a recommendation to the Senate at her request, he says. “I thought she was a breath of fresh air.” But after he’s seen her in action these past six months, his enthusiasm has dissipated. “Oh, gosh,” reflects Mouw, “I’ve been kind of disappointed in her positions” — especially on the disabled and the poor.

It’s not hard to understand why some might be shy about speaking on her behalf. With her suggestion that guns might be necessary in western schools against grizzly bears, and, most recently, the botched messaging that made the ED appear unduly sympathetic to the perpetrators of campus sexual assault, DeVos’s tenure has so far seemed like a litany of blunders and humiliations that have made her a target of protest and an object of ridicule. “She doesn’t have deep knowledge,” says Chris Minnich, executive director of the Council of Chief State School Officers, who has met with the secretary many times. “And without deep knowledge, you pretty much feel on the defensive.” Most mystifying to those invested in her success is why DeVos hasn’t found herself some better help.

Any career staffer at the Department of Education, for example, could have protected her from what was arguably her biggest gaffe: In February, she called the nation’s historically black colleges and universities exemplars of “school choice” — as if she didn’t know that HBCUs owe their existence to the fact that when it came to higher education, the Americans whose ancestors had been slaves didn’t have any choices at all. “Any career employee who saw that statement beforehand would have raised their hand and said, ‘Madam Secretary, no,’ ” says David Bergeron, a fellow at the Center for American Progress, who worked at the department for 35 years. “Either they didn’t see it before she gave it or they weren’t listened to. My assumption is that they didn’t see it.” (A ED spokesperson says, “More often than not press statements are being written by career staff.”)

Trump has hired other oligarchs to run his federal agencies, and he has staffed the Executive branch with people who, like DeVos, might have been called “lobbyists” in former lives. But DeVos is a hybrid of the two. Fortified by great wealth and strong religion in the shelter of a monochromatic community, she has throughout her life single-mindedly used that wealth to advance her educational agenda. DeVos believes passionately in “school choice,” the idea that poor families should have the same educational options as rich ones do — and that the best way to achieve this is to deregulate schools, creating an educational free market driven by consumer demand. (In the first regard, DeVos has good company; in the second, she is an outlier.) She was raised to believe she knew exactly what was right. And for decades, this certainty has propelled her ever forward, always with her singular goal in mind. But what’s right in the bubble in which she has always lived doesn’t translate on YouTube, or in Cabinet meetings, or on the battlefield of public schools, where stakeholders have been waging vengeful politics for years. This is what those advocates who had admired the zeal she brought to their cause didn’t have the foresight to grasp. Out of Michigan, without her checkbook, DeVos is like a mermaid with legs: clumsy, conspicuous, and unable to move forward.

“Perseverance and determination. Perseverance and determination.” This was the mantra of Betsy’s father, Edgar Prince, who made his billion manufacturing interior components of American cars: consoles, cupholders, armrests, and such. The illuminated, mirrored sun visor — a thing no one imagined they’d need — was his claim to fame. Prince was the richest man in Holland, Michigan, a grocer’s son, descended from Dutch immigrants who came to America to practice their faith. Holland is the kind of religious and ethnic American enclave, like Salt Lake City or Monsey, New York, where a dramatic homogeneity is preserved by geographic isolation. Clear on the other side of the state from Detroit, on the shores of Lake Michigan, it is a land of windmills and tulip festivals. The families in Holland tend to be churchgoing, Bible-reading Calvinists of Dutch descent who believe their lives on Earth are for the glory of God.

Edgar Prince and his wife, Elsa, raised four children, each named with an initial E. Elisabeth — Betsy — was the eldest. (Erik, who founded Blackwater, the private militia, is the baby, another heir to the family belief that private companies can do the government’s job better than the government.) The Prince children learned an abhorrence of social-welfare programs from a young age: Edgar’s father, Peter, died of a heart attack at 36, and as legend had it, Edgar worked to support his mother and two sisters from the age of 12. “My grandmother sought no government handouts, no charity from church, not even money from family,” Erik Prince writes in his book, Civilian Warriors. Like her siblings, Betsy attended a private Christian school at which football and dancing were forbidden. When she was a junior in high school, the Princes initiated a new tradition: They would throw a prom — with dancing — and pay for the band. In 1988, Edgar and Elsa were among the first big donors to the Family Research Council, the lobbying group affiliated with Focus on the Family whose stated mission is to “advance faith, family and freedom” in public policy. From its beginnings, FRC has been a cornerstone of the religious right, leading the fight especially against abortion rights.

After Edgar’s death in 1995, Elsa married a retired pastor and continued to give generously to FRC and its causes — including $450,000 in support of California’s Proposition 8, a state amendment banning gay marriage.

Betsy attended her mother’s alma mater, Calvin College, a conservative, intellectually rigorous Christian liberal-arts college in Grand Rapids, about a half-hour from her home. She was a political-science and business-administration major. It was there that Betsy Prince got serious about Dick DeVos. “I knew a guy who dated Betsy and was quite taken with her,” says Mouw, who was teaching at Calvin at the time. “And then Dick started dating her, and he had his own private jet and would fly her to Detroit to dinner. Nobody can compete with that!” The connection was dynastic. Dick was from Grand Rapids, also the firstborn in a Dutch family and also the heir to a massive fortune — one many times the size of Edgar Prince’s. His father, Richard (who is alive at 91 and worth more than $5 billion), had co-founded Amway, starting out marketing Nutrilite vitamins and building a vast army of salespeople with promises of personal freedom and profit. And while Richard DeVos was also raised on the hard wooden benches of a Calvinist church, he is a motivational speaker and author of self-help books, a devotee of Dale Carnegie and Norman Vincent Peale. “Being a capitalist is actually fulfilling the will of God in my life,” Richard has said, and in enjoying his wealth, he enjoys God’s bounty. “The first time I ever heard the word ostentatious, someone used it about Richard DeVos,” says Mouw.

The marriage of Betsy Prince and Dick DeVos consolidated enormous wealth and power in Michigan’s provinces. Now Betsy was invited to attend Richard DeVos’s quarterly family meetings, in which two generations of DeVoses and spouses discussed the most fruitful ways to spend their money. Since 1997, the family has given at least $44 million to the Republican Party. They own the NBA team the Orlando Magic and have given generously to conservative think tanks like the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, and, locally, the Mackinac Center for Public Policy and the Acton Institute. They have single-handedly rebeautified the city of Grand Rapids: The convention center, the performance hall, and a local hospital bear their name. (So, by the way, does an elevator in the new Whitney Museum in Manhattan: The DeVoses are conservative, but their interests are catholic.) Dick and Betsy, partners in everything, have their own philanthropy, which supports megachurches and Christian and charter schools, but also the X-Prize, which awards innovators in science and technology, and the Kennedy Center, where for six years Betsy sat on the board.

Friends say Dick is lovely to Betsy and deferential. Their four children attended private Christian schools in Grand Rapids. Betsy has said that she sent the kids to a more diverse school across town rather than enroll them locally, in their tony neighborhood of Ada. She has also said that she homeschooled her oldest daughter for a time and frequently pulled her children out of school so that they could come along when Dick, who became president of Amway in 1993, traveled abroad. “If you ask any of my kids today what their most important experience was in their education, they would say it was the travel and the ability to see and be in other cultures,” she has said. It’s an approach to education that wouldn’t be possible if they were, say, required to meet a public school’s typical attendance standards.

Betsy DeVos was first awakened to the struggles of poor parents after going on a tour of the Potter’s House in Grand Rapids, a private Christian school for disadvantaged kids. She was moved, she said, by the parents who would do anything to scrape together the tuition, which at the time was less than $5,000 a year, rather than send their kids to the local public school. “We knew we had the resources to send our kids to whatever school was best for them,” DeVos told Philanthropy magazine in 2013. “For these parents, however, paying tuition was a real sacrifice.” The DeVoses started sponsoring individual children at the Potter’s House, and sometimes even whole classes at $25,000 a year. In the mid-’90s, they arranged to give 4,000 private-school scholarships to low-income families — and got 64,000 applications. Betsy felt she needed to do more.

Relentlessness has long been DeVos’s most defining trait. “She is very strong. She knows what she believes and thinks and has both the will and the resources to pursue the things that she’s interested in,” says John Engler, the Republican former governor of Michigan, with a smile in his voice; he has known Betsy and Dick for a long time. He is fond of them and has experienced, firsthand, the consequences of crossing them.

After her visit to the Potter’s House, Betsy DeVos became one of the nation’s most aggressive activists for vouchers — government credits to help parents pay for the private or parochial school of their choice. Everyone agrees that in the country’s poorest Zip Codes, schools are mostly failing to serve children. But disagreement is virulent around the causes and solutions. Teachers unions hate vouchers because they funnel scarce per-student dollars out of public-school districts and into the private sector. Liberals regard them suspiciously as a Trojan horse: a way for religious or sectarian groups to erode First Amendment protections and take control of schools. Will government dollars be spent, for example, to teach American children that God created the world in a week? Or to support schools that maintain exclusionary admissions policies? A coalition of reform-minded progressives, many of whom are African-American leaders from impoverished urban districts, including Democratic superstars like Cory Booker, continue to support vouchers. “I think it’s insulting that people can wax eloquent about what poor children of color should have to accept when they have all the options,” says Kevin Chavous, a Democratic friend of DeVos’s who was instrumental in bringing charter schools and vouchers to Washington, D.C. Nonetheless, for years vouchers were regarded as a losing proposition.

The DeVoses believed otherwise. For Betsy, the right of parents to determine what is best for their kids obliterated all other social concerns, and in 1996 she became co-chair of Of the People, an Arlington, Virginia–based lobbying group intent on amending state constitutions with the following language: “The right of parents to direct the upbringing and education of their children shall not be infringed.” Of the People took particular aim at public schools, which it conceded were necessary to maintain minimum discipline and academic standards but too frequently overstepped their role. “There’s not a consensus,” said a spokesman for the group at the time, “that it’s the school’s job to hand out condoms, to psychologically test children, to give them a version of history that’s contrary to what their parents teach, to emphasize self-esteem and other fluff over reading, writing, and arithmetic.” The parental-rights amendment found its way onto the ballot in two dozen states and failed in all of them.

“Parental choice” — or vouchers — was a short conceptual hop from parental rights. Milwaukee, just across Lake Michigan from Grand Rapids, had launched the country’s first voucher program in 1990. And in 1999, when Engler was governor and Betsy DeVos was head of the Republican Party in Michigan, Dick DeVos got together with the state’s Catholic bishops and a coalition of African-American pastors from Detroit to found “Kids First! Yes!” — an effort to put vouchers on the ballot in Michigan. He would spend, he said, whatever it took to see the measure pass.

Engler refused to back the initiative. He saw that it was futile — a waste of time, money, and political capital — and said so publicly. Voucher proposals had recently been defeated in Texas, Pennsylvania, and New Mexico, and a voucher bill that passed in Florida had been overturned by the courts. George W. Bush was running for president and considering Engler as his vice-president. As governor, Bush had supported the Texas voucher legislation. Now he hesitated to use the word vouchers on the stump. “I was involved in enough battles,” Engler says now. “I just didn’t think that we were there. I was trying to play a longer game: If you wait, your probability of success goes up greatly. That’s what politics is.”

The DeVoses were incensed. Betsy abruptly quit her job as state-party chair, informing Engler by voice-mail. The DeVoses were the Republican money in Michigan. They did not want their generosity to be mistaken for altruism. “I have decided to stop taking offense at the suggestion that we are buying influence,” Betsy wrote in 1997. “Now I simply concede the point. They are right. We do expect something in return … We expect a return on our investment.” Dick and Betsy threw themselves into “Kids First! Yes!,” raising more than $12 million, a third of which was from the family’s own coffers.

The measure lost, overwhelmingly. “If they had won, I would have looked pretty silly, and she would have been proven to be prophetic,” Engler says. “I thought I knew. In this case, she thought she knew, too.”

In defeat, Betsy DeVos reapplied herself. If she couldn’t stimulate demand by giving poor parents vouchers, she would increase supply by expanding the educational options available to them. She founded the Great Lakes Education Project, an activist organization to foster the growth of “charters or vouchers or magnet schools or contract schools or virtual schools or options that had not yet been developed,” says Gary Naeyaert, former executive director of GLEP. In a 2002 speech to the Heritage Foundation, Dick DeVos explained GLEP’s strategy: In any state vote on “school choice,” the DeVoses did not want a single Republican to swing against them and join with Democrats and teachers unions. And so they would focus on the primary field, rewarding local candidates who declared allegiance to their cause and punishing those who refused. “It does change the nature and the scope of the debate when you’re able to deliver help to your friends and consequences to those who oppose your agenda,” he said. And in 2011, through the efforts of GLEP, the Michigan State Legislature passed a law allowing the largely unfettered and unregulated proliferation of charters throughout the state.

Detroit now has a greater percentage of kids in charters than any city in the country except New Orleans. Eighty percent of those charters are for-profit. The number of charter schools is growing while the number of students in Detroit continues to shrink, so schools pursue kids like retailers on sale days, with radio ads and flyers and promises of high-end gifts. Still, only 10 percent of Detroit’s graduating seniors are reading at a college level, and the charter schools perform better than or as well as the district schools only about half the time. When last summer a bipartisan group of concerned Detroiters tried to introduce some accountability and performance standards to the system, GLEP stepped in and killed the measure.

DeVos has taken her campaign nationwide, founding the American Federation for Children, an advocacy group whose Washington-based PAC backs politicians across the country who support “school choice.” Now 25 states have “private school choice” programs, which are not always called vouchers but sometimes “scholarship opportunities.” “Our work in Michigan was so successful that some of our friends in the movement began to say, ‘We really need to do this nationally,’ ” DeVos said in 2013, “and I said, ‘Yes, I think we do.’ ”

To what degree should the federal government be involved in local schools? For over 20 years this question has been a culture-war front, and DeVos has clearly picked a side. (It is no accident that conservatives have appropriated “choice” for themselves. In his Heritage Foundation speech, Dick DeVos quipped that he was “pro-life and pro-choice.”) But in the daily responsibilities of the Department of Education, the answer to that question requires compromise and diplomacy. If control of schools broadly reverts to the states, then who makes sure that all kids are learning what they should? (And what, in the 21st century, should they even be learning?) If charter schools and for-profit schools and voucher programs are encouraged to proliferate, how is their performance measured and who guards against exploitation? Is it the federal government’s job to protect the vulnerable against abuse — like rape, or discrimination, or bullying — at schools? And what about financial aid? Does the government have an obligation to make higher education affordable, or to guard kids and their parents against profiteers, or to assist working parents with after-school programs? As a crusader, DeVos didn’t have to consider these complexities, but now that she’s secretary, it’s her fundamental job.

Just days after her confirmation, DeVos attempted to demonstrate her authentic interest in public schools by visiting one — Jefferson Middle School Academy, in southwest Washington, D.C., steps from the ED. Teachers unions had organized against DeVos in advance of her hearing, and now the head of the D.C. union had alerted teachers and parents groups. By the time the government cars were approaching the building, several dozen protesters had arranged themselves in front of the school, holding signs and chanting, “Stand up! Fight back!” DeVos has never offered full-throated support for the nation’s public schools, which educate 80 percent of America’s kids, sometimes very well; in a 2016 editorial, she suggested that the solution to the problems besetting Detroit schools was to shut down the district, replacing it with a free-market model to “liberate all students.” When DeVos’s car circled to the back parking lot, a smaller group of activists confronted her and formed a human chain, trying to block her entrance. One man chased her car and was restrained by police. The video shows a thin-lipped De Vos hurrying to the car, with a bodyguard firmly holding her arm.

The following week, DeVos got a security detail of U.S. Marshals, the first Education secretary ever to have one: 22 guards, six on duty at a time, which will cost taxpayers at least $7.8 million this year. There was widespread outrage among the department’s rank and file, for Trump has made no secret of wanting to reduce the number of federal employees. “I mean, let’s say the average federal salary at ED is 80k,” says Charles Doolittle, a career employee who quit the department in June. “That unnecessary security is 100 employees. They’re freezing hiring, even considering buyouts, and possibly layoffs? And if the security really is so terribly necessary, then why doesn’t the billionaire pay for it out of pocket?”

Doolittle, as well as department staff who won’t speak on the record for fear of retribution, says DeVos’s management style is just this way: polite on the surface — “nice” — but disconnected from the people she is charged to lead. Insiders say DeVos rarely asks staff to comment on her public statements, and when they do comment, they are thanked for their suggestions and ignored. At meetings, staff are reminded not to talk to the press. “When you talk to her, it’s a blank stare,” says Doolittle. Since her confirmation, DeVos has been making the rounds, shaking hands in the halls and dropping in, casually, at the cafeteria. But to some it feels superficial. At a December rally with Trump, DeVos had vowed that under her leadership, the nation’s education problems would be solved locally — not through “a giant bureaucracy or a federal department. Nope” — remarks that seemed to disparage the role of the department itself.

DeVos believes that “a child’s progress — or lack thereof — is fully transparent to his or her parents,” and that therefore “we should be focused on investing in individual students, not buildings or systems.” But she has yet to articulate how to govern from that position. “It almost feels like they’re not clear on their strategy quite yet,” says Minnich. According to friends, she supported the Common Core, an Obama-era federal template governing what kids should know, and then, as she entered the Trump zone, reversed herself. She apparently opposed the president when he rescinded protections for transgender students — and then caved. She has insisted on local control of schools and then proposed a $1 billion program in which the federal government incentivizes states to adopt school-choice policies. In perhaps her most mystifying move to date, DeVos posted plaudits for Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris climate accord on the Department of Education’s website, an international concern far outside her jurisdiction.

Within the department, morale is low and the mood is tense. “People aren’t sure about who’s making the decisions,” says one veteran. “It’s not clear that the secretary is making decisions or really capable of understanding the elements of a good decision … I don’t know if it’s decision by committee, or if one person speaks more strongly than others, but different people come to us with different decisions. One person says something one day, there’s disagreements, then someone else comes in and says, ‘Let’s do something else.’ ” (Senior staff provided by the department say she’s “fully engaged” and “makes very quick, swift decisions and the right decisions.” And the press office says the chain of command is clear.)

As in other federal agencies, hiring has become a crisis for DeVos, with qualified candidates declining to join her band. No one wants to be deputy secretary, the No. 2 job, and DeVos has interviewed many prospects. No one wants to be undersecretary either, with responsibility for higher ed. (A longtimer named Jim Manning was brought out of retirement to assume the “acting” role.) Hanna Skandera, who ran New Mexico’s schools, had been DeVos’s choice to lead elementary and secondary ed but was dinged by congressional Republicans because she supported the Common Core. (Now that job is filled by Jason Botel, a charter-school operator and Democrat, who is viewed by conservatives as somewhat more restrictive toward state freedoms than they expected and by DeVos opponents as a glimmer of hope.) In a statement, a ED spokesperson suggests that the White House and Congress are to blame: “When the secretary is able to hire freely, she’s able to find incredible candidates and get them onboard quickly.”

In fact, DeVos is the one political employee in the department to have been confirmed by the Senate (and that by a hair). Every other person leading a division has taken a temporary, acting role. Thus Candice Jackson, the white lesbian lawyer who during the 2016 campaign gathered the alleged victims of Bill Clinton together for a photo op at Trump’s second debate against Hillary Clinton, is Education’s acting assistant secretary of civil rights. As victims’-rights groups wait to see whether DeVos will dial back Obama-era protections for victims of sexual assault, Jackson has recently signaled special sympathy for accused men and boys, saying that 90 percent of accusations “fall into the category of ‘We were both drunk’ ” and “ ‘Our last sleeping together was not quite right.’ ” (She later apologized for being flippant.) Carlos Muñiz, who is acting general counsel, represented Florida State University against a charge that it failed to investigate a rape accusation against a star player of its football team.

The impasse around staffing contributes to DeVos’s ineffectiveness. Kevin Chavous says that his friend is being constrained — “muzzled” — by the Trump White House into a kind of paralysis. She is surrounded by “all the same types. Conservative Republicans. Trumpites,” who are feeding her talking points about state rule without helping her understand the context or the fault lines around education policy, the larger questions of race, poverty, inequality, family structure, and health care that failures in school systems raise. “In education, the first thing you should do is make sure you have as many diverse voices as possible, especially since 51 percent of our kids are on free and reduced lunch. You cannot have education policy shaped by people who do not look like the people you’re serving.”

Meanwhile, DeVos, responding to an executive order, is undertaking a massive bureaucratic reorganization. Staff at the Federal Student Aid office have been asked to think about what a consolidation of their operations over at the Treasury Department might look like. Similarly, there’s talk of the Justice Department’s absorbing the functions of the Office for Civil Rights. Power has coalesced around DeVos’s chief of staff, Josh Venable. A Michigander who went to a small Christian college and previously worked for the Michigan Republican Party (which DeVos has chaired) and Jeb Bush’s education philanthropy (where DeVos sat on the board), Venable “is the king,” says one insider.

Charles Doolittle decided to quit while at work, watching DeVos on C-span. She was defending her budget to a House subcommittee in May and was much better prepared than she had been in her confirmation five months before. But under fierce questioning from Representative Katherine Clark of Massachusetts, DeVos seemed to fold. Would the federal Department of Education protect a gay child who wanted to use a school voucher to attend a school with anti-gay admissions policies? DeVos stumbled. She started. Then stopped. Then started again. “States and local communities are best equipped to make these decisions,” she concluded.

“I didn’t think I would ever see a Cabinet member who couldn’t say for the cameras, ‘Oh, we would never discriminate against x, y, or z population,” says Doolittle. “I sent an email to my supervisor saying, ‘We’ve got to talk. I’m out.’ ”

On Valentine’s Day, DeVos accepted an invitation to speak at the dinner preceding Capitol Hill Day, in which the athletes of the Special Olympics pay visits to their representatives in Congress. It was just after her confirmation, and some attendees were wary of the controversy her presence might provoke. But DeVos was gracious. “I’m proud to stand beside you as a partner and support Special Olympics — an important program that promotes leadership and empowers students to be agents of change,” she said in her prepared remarks. Her duty being discharged, another Cabinet secretary might have made excuses and an exit, but DeVos stayed, visiting with the athletes and their families at each table. She chatted and shook hands and took pictures with everyone — as if these were the most powerful people in the country and not the least.

There are other stories like this about DeVos, about her sitting in the front rows of the Mars Hill megachurch outside Grand Rapids, wedged between the single mom and the migrant from Ecuador, rapt as the founding pastor of the church, a progressive Christian named Rob Bell, preached about social justice and God’s imperative not to judge — not gays or Muslims or anyone else. “There would be a loud rock band playing,” says Richard Mouw, “and Rob Bell in his T-shirt and skinny jeans preaching, and here’s Betsy in the middle of that. Why was she attracted to Rob Bell? Was he offering an alternative to the kinds of conservative patterns of thinking that she was raised in?” Church members recall Betsy and Dick there with their kids, picking up paper plates after a picnic, just like everybody else, mentoring students in impoverished local schools and enthusiastically supporting the church’s work with aids orphans in Africa. “I love Dick and Betsy DeVos. They care more about poor kids than anybody ever could, and the difference is they actually do something about it,” says Tom Maas, who served with Betsy as an elder at Mars Hill. Her friends call Betsy decent and good-hearted, authentic and vulnerable.

Some of the people who know this side of DeVos were thus more astonished than anyone to see her defending a federal budget that in its initial form proposed $9 billion in cuts when it was released in May, a reduction of 13 percent. It eliminated after-school programs, mostly for poor kids. It killed professional development for teachers. It targeted arts programs, foreign languages, child care for low-income parents in college. It nixed a program meant to encourage integration in the nation’s most segregated schools. The only significant additions (aside from DeVos’s security detail) were $1 billion to stimulate “school choice” programs in the states and another $250 million to expand school-voucher programs. But when the House Appropriations Committee passed its funding bill in late July, that money for school choice and vouchers wasn’t in it. DeVos’s admirers point out that she doesn’t need this job. To see her passion project summarily executed by her Republican colleagues must have been bruising indeed.

That must have been how Tim Shriver, chairman of the Special Olympics, felt when he read one morning in the Washington Post that his entire federal budget had been killed. The Special Olympics receives about $12 million annually — which it matches with private dollars — for a program that rewards schools for including disabled athletes on their sports teams and has been proven to reduce the depression and isolation that disabled students feel. Republicans like the program. So do Democrats. It’s not that much money, and spending it makes everyone feel good. Another Cabinet secretary — especially one who stood up and publicly identified herself as “a partner” of the program — might have given the chairman a heads-up in advance, made future promises, or bought goodwill, but “we were given no advance notice that we were going to be eliminated from the president’s budget,” Shriver says. Perhaps this was another blunder, another unintentional oversight, but the result is the same: The kids who were at the Marriott that night will be the first to recognize a bully when they see one, no matter how graciously she shakes hands.