Two lawyers, a summer of unrest, and a bottle of Bud Light.

It’s an audacious choice to pause in front of an Applebee’s restaurant on Flatbush Avenue and grant an impromptu interview to a video journalist shortly before you allegedly throw a Molotov cocktail into a police car. But the city was out of its collective mind that night, the Friday after the Monday George Floyd was killed. Urooj Rahman faced the camera looking high-strung and distracted, answering questions as her hands waved and flitted around her body and in front of her face as if they were birds escaping from a box. Rahman emigrated from Pakistan when she was 4 and now lives with her elderly mother in Bay Ridge; she works as an attorney at Legal Services in the Bronx, representing tenants without means in eviction proceedings. “This shit won’t ever stop unless we fucking take it all down,” she said. “We’re all in so much pain from how fucked up this country is toward Black lives. This has got to stop, and the only way they hear us is through violence, through the means that they use. ‘You got to use the master’s tools.’ That’s what my friend always says.”

Sometime later, around 1 a.m., Rahman apparently threw a Bud Light bottle, filled with gasoline and lit with a toilet-paper fuse, through the broken window of a parked, abandoned cop car that had already been vandalized. According to the government’s complaint, there were witnesses. And because nothing happens anymore without documentation, the government says that police surveillance cameras recorded the act, and a photographer captured Rahman an instant before, leaning out of her friend Colinford Mattis’s tan Town & Country van, holding the bottle stuffed with tissue but still unlit. In the dim background of the photograph, Mattis is driving, his head and gaze tilted away. The government says that after the bomb ignited, destroying the console of the NYPD vehicle, the two drove off. The police gave chase and, when they caught up with them, found a lighter and another Molotov cocktail in the passenger seat and the materials for making more in the back.

A short, edited clip of Rahman’s video interview circulated with the first news stories, stoking widespread curiosity, incredulity, empathy, and pain: a lawyer who had come of age in an increasingly activist mainstream left speaking the language of abolitionist Twitter and looking to some on the right like a new breed of homespun terrorist. Mattis was the bigger mystery; the son of immigrants from the Caribbean, raised by a mother who was a home health aide and a foster parent, he never seemed the revolutionary type. He was a corporate lawyer who — after being plucked out of East New York by the scholarship program Prep for Prep — played football at boarding school, joined two eating clubs and a jockish fraternity at Princeton, and, after NYU Law, worked at Holland & Knight and Pryor Cashman, firms where first-year associates earn upwards of $150,000 a year. All his friends say Mattis seemed to wear the world lightly. He was a social guy, a positive force, always available to give friends a ride, always reading a book on the bus, a fashion agnostic who carried the same gray backpack he used in middle school.

Rahman threw the bomb; Mattis just drove. Or at least that’s how the story came together on social media and in the press. But the unedited version of Rahman’s interview complicates that account. Mattis was with Rahman on Flatbush Avenue that night. If you look carefully over her right shoulder, you can see the tan van parked at the curb. The interviewer asks Rahman a question: “We’ve seen police cars on fire and objects thrown at police, fireworks and that kind of stuff. How do you feel about that?” When Mattis enters the frame, apparently from the direction of the 7-Eleven next door to Applebee’s, he is wearing the clothing you see in his mug shot: brown hoodie, black tank, and loose gym shorts. And he is carrying two bags: a large, heavy, squarish one in his left hand and a small, light, cylindrical-looking one in his right. He is masked, and he walks past Rahman without acknowledging her, so casual as to be almost invisible, to the van where he clicks open the back door and puts the packages in. (Mattis’s lawyer declined to comment on the video. An early news report in the New York Times said some of the materials for the Molotov cocktail were purchased at a convenience store near where Rahman stood.)

Rahman answers the interviewer. “It’s understandable,” she says, not looking at Mattis, wrapping and rewrapping her scarf around her face. “This is the way that people show their anger and frustration,” she says a minute later. “Because nothing else works. Nothing else.” She remains unfailingly polite. At the conclusion of the interview, the video journalist asks her name and she tells him. And then she spells it. U-R-O-O-J.

More than 200 people were arrested in New York City on the night of May 29–30, including Rahman, who is 31, and Mattis, who is 32. Most of the demonstrators were released the next day, but Rahman and Mattis were held for hours at the 88th Precinct in Clinton Hill, interrogated, taken into federal custody, and finally charged with seven federal crimes — including arson, conspiracy, and the commission of a “crime of violence” using a “destructive device,” a charge that carries, if they are convicted, a mandatory minimum sentence of 30 years. Altogether, Rahman and Mattis each face nonnegotiable sentences of 45 years to life.

To be a lawyer is to agree to play by the rules, or at least to acknowledge that the rules exist, even as you seek to bend them. And it is this simplistic, romantic understanding of a lawyer’s job that is part of what has the government so provoked, as if going to law school is or should be a safeguard against breaking the law. “The conduct,” said U.S. District Court judge Margo Brodie in reference to this case, was “completely lawless.” At a recent bail hearing, one of the prosecutors argued similarly. “These were lawyers,” he said, “who had every reason to know what they were doing was wrong and knew the consequences. Committing this crime required a fundamental change in mind-set for them.”

But to work within that system is to understand just how capricious and brutal criminal justice can be — the enormous latitude given to prosecutors, the deference extended to judges and juries, and the procedural protocols and professional ethics that often merely cover for the status quo. And when a president and his advisers seem to regard the law as an obstacle course; when an attorney general metes out favors, not justice; and when immigrant children are held in cages and men are killed on video by police, some lawyers may want to embrace a more flexible definition of “lawless.” As recently as a few years ago, even a progressive-minded lawyer might have regarded fervent, visible participation in a political protest as professionally unbecoming. Today, some of Mattis and Rahman’s friends may concede in private that throwing a Molotov cocktail represents a lapse in judgment, but none are willing to discuss the degree to which their friends may have been ethically, professionally, morally, or legally out of bounds. Instead, they emphasize that violence against government property, especially in the midst of political upheaval, is not the same as violence against a person; that the prosecution of their friends for an act of what amounted to political vandalism is far more extreme than the crime itself; that it amounts to a criminalization of dissent and reflects a broader right-wing crusade against people of color and the progressive left — and, as such, demonstrates precisely the horror of the system they were out in the streets that night to protest. There is a version of the Rahman and Mattis story in which they are civil-rights heroes, even martyrs, instead of professionals who crossed a line.

These are people the least deserving of this kind of treatment, their friends say, people who are unfailingly kind, gentle, and decent. Rahman gave a piece of her apartment floor in Athens, Greece, where she was working during the migrant crisis, to a queer Syrian refugee in an abusive relationship; Mattis turned around on his way to vacation to sit by a friend’s hospital bed after she’d suffered a stillbirth. After college, Mattis worked for Teach for America in New Orleans and later won a prize for his pro bono work helping a single mother get child support. Rahman worked in Northern Ireland and on behalf of hill-tribe people in Thailand and was a student of South African apartheid. Over the past year, she started attending Friday-night meetings of an informal Sufi spiritual group and had recently given a short talk to a Muslim women’s group about the sacredness of every single life, including those of animals — which is why she tried to be a vegetarian although sometimes fell short. She joked that she was a “slackaterian” or “vegetrying.”

“My heart — and I speak for many of our friends — my heart has been breaking,” says Tabatha Robinson, who met Mattis through Prep for Prep and has just graduated from Harvard Law. When Robinson was a teenager, Mattis would travel from Princeton to her New Jersey high school to watch her ballet recitals because she’d confessed to him her dream of becoming a ballerina. “What college boy shows up at their friend’s high-school ballet recitals?” She starts to cry. “Forty-five years to life? Are you kidding me? I want a world in which our sentencing doesn’t look like this.”

Mattis and Rahman are not, nor have they ever been, a couple, their friends say. The press is painting the night of May 29 as this “weird Bonnie and Clyde situation,” says someone close to Rahman. “It’s so freaking ridiculous. Colin is like a cute, lovable baby.” What Mattis and Rahman do share are life circumstances that set them apart from their friends, most of whom were raised with more privilege. Each of them lost parents comparatively young. Rahman’s father died suddenly when she was 23; Mattis’s died in a stabbing on St. Vincent when he was in law school, and his mother, a powerful presence in his life — and a fervent Christian — died last summer. So they both know early grief and loss, and as the responsible, high-achieving adult children of immigrant parents, they stepped in to shoulder more than their share of the family obligations, while their peers were far more carefree. Rahman looked after her mother, doing the shopping and ferrying her to doctor’s appointments. Mattis took over the raising of his mother’s three foster children after her death. Their relationship is more “like brother and sister,” says Salmah Rizvi, who co-hosted the birthday party where they met. “Like, they take care of each other.”

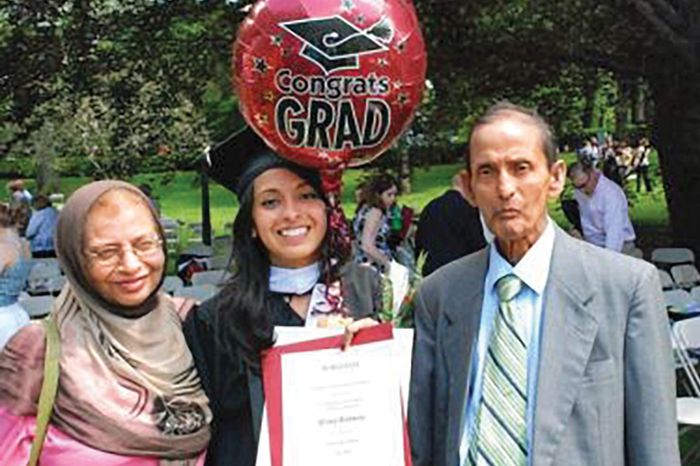

Rahman with her parents at her Fordham University graduation ceremony in 2011.Mattis holding an award he received from Her Justice while working with Holland & Knight in 2019

It was the fall of 2014 when Rahman and Mattis became friends, in the wake of Michael Brown and Eric Garner’s deaths, the year after the birth of Black Lives Matter. Rizvi had gotten close to Rahman that summer when they traveled together on a law-student fellowship to Israel and Palestine. Most law students start looking for jobs between their second and third years, and an alignment with Palestinian human rights could have been regarded by some as a career-risking move. Upon arriving in Israel, Rahman was stopped and questioned at Ben-Gurion International Airport for more than four hours; already, she was steeped in the language of social justice and racial politics, friends say. All summer long, as race-related anti-police uprisings spread across the U.S. and the Israeli military bombed homes in Gaza, the parallels between the American Black struggle and Palestinian oppression were a topic of conversation among the fellows (excitedly sharing rumors, for instance, that tear-gas canisters used in Ferguson are the same as those used on the Palestinians in the West Bank), and they used the word apartheid to describe the conditions they saw there and at home. Rahman was “very vocal,” one person says; at home, she was already studying discrimination by the NYPD in Arab and South Asian communities. She marched in Haifa in July with Palestinians against Israeli forces, and, upon returning home, wrote an essay decrying Israeli-military violence. “IDF soldiers provoke violence using tear gas, stun grenades, rubber-coated steel bullets, and often, live ammunition at civilians exercising their free speech,” she wrote.

For many of the young law students, the trip was galvanizing. “We were about to graduate, to become American lawyers, and the question was: How were we going to pursue this, involve the struggle in our work?” says Jordan Manalastas, who was in the program and is now a public defender for detained immigrants.

Mattis was also marching that fall. His roommate at St. Andrew’s boarding school, still a close friend, was Ikenna Iheoma, who was working at NBC Sports in 2014. Iheoma remembers, especially after Garner’s killing, feeling the responsibility as a Black man to stand up for other Black men and seeing that somehow popular opinion in the U.S. was still not united behind the victims of police violence. “It was fifty-fifty,” he says. One night, Mattis gathered a bunch of law students to march, and Iheoma came downtown. “I obviously joined in. It was a time when there were protests everywhere. The NYU law students went outside and held up signs and started marching, and as we were walking along and demonstrating, more and more people joined.” Most of the protesters were Black or people of color — as if the rest of the world weren’t ready or able to digest what it meant to watch a human die on video at the hands of police. “We were like, Okay, this is really bad,” he says. “We were 25, 26, at the time.” The late Obama years were studded with protests like these: A younger, more dissatisfied generation was rising up.

Iheoma was speaking to Mattis on the phone the Thursday before his arrest. Iheoma lives in Harlem, and they were talking about getting their dogs together in some park midway between them. (Mattis has a goldendoodle named Lorde Hampton.) They were marveling, as they had been for days, about how different it was now with so many people out in the streets — so many white people. The demands for police reform and accountability were no longer fifty-fifty but a scream in unison, and the friends were wondering, in this altered reality, about their role. They were full adults now: a corporate lawyer and a health-tech entrepreneur. Mattis had not told Iheoma that, because of the pandemic, he had recently been furloughed. “Should we be on the front lines? Should we be using money to donate more? Are there other things we can do this time that we weren’t able to do last time? Should we take a step back and let the younger people of color take the forefront, like we did six years ago?”

Rahman and Mattis on the night of their arrests. Photo: Stephen Yang/Polaris (Rahman arrest); Seth Gottfried (Mattis arrest).

There’s a certain kind of Muslim kid who grew up in New York after 9/11 extremely aware of how it feels to have the world suddenly suspect you as the enemy. Richard Lubell watched a lot of these kids pass through his classroom at Brooklyn Tech. In 2006, when Rahman was a junior, she took his civics-and-law class, he said in an interview. He observed that — whereas previous generations might have stuck more closely to the straight and narrow, believing that if they worked hard, the world would reward them — Rahman’s cohort of kids was more “free-form, adventurous, bohemian, some version of that,” he said. “Somehow, the rules about success were tarnished, and they had to go out there and make their own rules, make meaning themselves. The world had become a more insecure place, more foreboding, and these kids were searching for a way to find meaning, whether you became a filmmaker or a world traveler or an activist lawyer. I may even have said that in class — that it was good to become an activist lawyer.” Rahman told Rizvi that it was Lubell who had inspired her to become an attorney.

Lubell himself, who retired from teaching three years ago, is a leftist, a self-proclaimed “third-party activist — maybe less identified with the Democratic Party per se,” and in his civics-and-law class, he held mock elections “that were parliamentary. It wasn’t a winner-take-all kind of thing. We practiced ranked voting, a way of distributing power,” he remembered. Class discussions were based on the law around actual news events, which, in the years after 9/11, included due process, equal protection, and search and seizure. Many teenagers in the school at the time were regularly stopped by police when entering the subway and told to hand over their backpacks for inspection. Lubell said that, in class, Rahman was “always a tough girl, kind of feisty and tough, and always fighting for the underdog.”

“She calls herself a cat,” says one of her friends. “She takes on this cat persona; she says she can talk to cats, like a cat whisperer. She’ll say, ‘I’m just going to be a cat and sit here.’ ” All the friends mention, unprompted, her stringent environmentalism, how she would chide them for buying plastic bottles of water at the deli or for using disposable grocery bags. One recalled a time when Rahman was about to come over but first sat alone in a restaurant eating sushi, rather than contribute to the convenient waste created by takeout containers.

Mattis was, in some ways, the opposite. He had grown up a compulsive joiner. At St. Andrew’s, the setting of Dead Poets Society, Mattis played football, though he wasn’t much good. He wrestled in the winter, and in the spring he was in the play. Together with school friends, he went to Washington, D.C., and marched for Darfur, meeting then-Senator Barack Obama and insisting on a photograph, and he participated in an annual aids walk. At Princeton, Mattis joined both Cap and Gown, one of the most selective of its eating clubs, and Terrace, one of the least. He joined DKE, a beer-pounding fraternity, at the urging of friends. “I specifically remember him saying, ‘They do community service, so why not?’ ” a friend from the time remembers. “It was a ‘why not?’ thing. It was one of the many circles he ran in.” Mattis took an intro course to African-American studies with Cornel West, had leadership roles in the Black Student Union, and helped to organize Popeyes study breaks. At college, he sometimes went to Bible study. (Later, he was known for telling friends who were feeling blue that “God on high acts on low” and at the same time urged friends discouraged by the dating scene to get out there. “Anybody with a body can get bodied,” he would say.)

Wherever he lived — whether in the dorms or, more recently, in a beautiful three-bedroom apartment in Crown Heights with a balcony and roof access, the extra bedroom of which he would Airbnb, so there was always a Japanese or German tourist around — became the place where people got together. Andrew Devlin lived next door to him on their hall in high school and remembers his particular interest in questions of equity in education. Mattis’s way was to talk, dissect, agree, disagree, and talk some more, to the point where a bunch of teenage boys were sitting around the dorms at “two or three o’clock in the morning to figure it out,” Devlin says. “What was the best way forward? Going to Prep for Prep? Was the answer to take gifted kids like him and give them a really good education? Or was it better to just focus on public school and improve the baseline education for kids around the country?” In his senior year of high school, inspired by the mash-up in his mind of the material in his colonialism class and the Kanye West song “Diamonds From Sierra Leone,” Mattis put together a forum on diamond mining. He wrote about its effect on him in the alumni magazine: “By talking about this issue that was basically new to all of us, we learned that in everyday life we contribute to injustices in places far away and out of sight.”

Since last summer, Rahman had been working at Bronx Legal Services, where she belonged to a team of roughly 60 lawyers representing people who want to fight eviction proceedings but can’t afford an attorney. On the Friday night before her arrest, Rahman was on a Zoom call until about 6 p.m. It was a union meeting. After a months-long hiatus, the courts had begun to schedule hearings so pending eviction cases might resume, and the defender-advocates at Bronx Legal Services objected strenuously. “Everything was happening with George Floyd,” says someone who was on the call. “And I don’t know about you, but I was still hearing sirens. And the courts are like, ‘Get those evictions done.’ ”

About 20 people attended the meeting, the purpose of which was to share information. Rahman didn’t say much, which was typical for her at work. The job at Bronx Legal Services is grinding — many of the clients live in extreme poverty and chaos, processes are sticky, and judges and plaintiffs’ attorneys can be petty, racist, sexist, and mean — but Rahman was always “very chill, very easygoing,” says the same co-worker, a collaborative colleague, compassionate and diligent with her clients and levelheaded in court, willing to engage with the small-bore, unglamorous work of advocating for the vulnerable within the frustrating constraints of the law. Unlike the earnest, paternalistic types who might have previously chosen Legal Aid as a career, the youngest lawyers at Bronx Legal Services have a radical strain — some wear tattoos reading RENT IS THEFT — but Rahman never seemed to be part of that. Any number of her colleagues might have been accused of throwing a Molotov cocktail into a cop car, and the news would have been met with an unsurprised shrug, this colleague says: “Eh, that checks out.” But Rahman came across as so calm. “I was shocked.”

Mattis’s friends were in disbelief. He was always conciliatory, never confrontational. “He’s not a person to bring down the mood,” Iheoma reflects. “He doesn’t like to put that burden on people.” But when his mother got sick, Mattis struggled. After she died, he moved out of Crown Heights and back to East New York to help care for the three foster children (the oldest is 11) who were under her care. “Colin didn’t have the luxury of stressing about the things that people in the upper echelons of society stress about,” says Eric Plummer, one of his closest friends at Princeton. Instead, he compartmentalizes. “He does get stressed, worried, concerned — like, pensive. He becomes introspective. You have to know him to know when he’s stressed; it’s like something is off.” Mattis didn’t tell Plummer that his mother had died until months after the fact, and he did so in a sideways fashion. “He said, ‘Oh, by the way, I have kids now,’ ” says Plummer. “I was like, ‘What are you talking about, Colin? It takes nine months to make a child.’ ”

Jazzy Ellis, another Princeton friend, was texting with Mattis the week George Floyd was killed. Ellis is a stuntwoman, dependent on movie production for survival, so she was already feeling unmoored after months of unemployment and isolation. After the video began circulating, she went for a drive just to clear her head — she lived alone in Atlanta at the time — and was called the N-word three separate times. Upon arriving back home, she began reaching out to her Black friends and texted Mattis. “I was just trying to connect with other people who might be feeling the same way. I guess I was feeling scared,” she says. At Princeton, Ellis was perhaps more self-protective than Mattis and immersed herself more exclusively in the Black student organizations on campus, while he was more outward facing, “a connector,” she recalls. “Very happy, happy all the time. Always smiling. A chipper, super-positive guy,” though if you watched him closely you could see “a little aspect of sadness through his smile.” In their texts that afternoon, she and Mattis talked about “how confused we were, in this situation, in this pandemic, feeling how we were as Black people in America. I was unemployed. I believe he was furloughed. We weren’t really grounded. We were both pretty low. I could see how it might lead to something drastic. We were only texting, but it felt like he wasn’t smiling anymore.”

Their mug shots. Photo: Courtesy of U.S. Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of New York

The prosecutors in the national-security unit of the Eastern District of New York — as close to Trump Land as one gets in Brooklyn — must have celebrated when they saw the NYPD record of the arrest: “This case was so juicy for them,” says a public defender who is familiar with it. “It’s a perfect storm of ‘Antifa is a terrorist organization, and here are two lawyers of color we can hang out to dry.’ ” (The Eastern District declined to comment for this story.)

There were meaningful and consequential ways to charge Mattis and Rahman under state statutes, but sometime on May 30, their case was bumped up to the Feds; by that night, Mattis and Rahman were being held at the Metropolitan Detention Center, the same federal facility in Brooklyn where Ghislaine Maxwell is now being held. After signing the indictment for Mattis and Rahman, the U.S. Attorney in the Eastern District originally in charge of the case, Richard Donoghue, moved down to Washington, D.C., to work under William Barr in the Justice Department.

Their mug shots indicate that, in the early morning hours of May 30, Mattis and Rahman may not quite have comprehended the trap they were in. Mattis looks startled, a little lost. Rahman wears a small smile, defiant. As lawyers immersed in social-justice struggles, they might have predicted the antagonism of their own government, but even so, the full force of federal prosecution was surely disorienting. The federal indictment, filed on June 11, makes a case for domestic terrorism. It charges Mattis and Rahman with conspiracy. It describes the police car as a vehicle “used in interstate and foreign commerce.” It categorizes the Molotov cocktail as “an incendiary device,” which, in the legal code, includes homemade bombs along with grenades and missiles. The use of this type of “destructive device” in a “crime of violence,” with which Mattis and Rahman were also charged, carries a minimum sentence three times what it would have been if they had instead used a gun.

To those on the progressive left, that makes for an illuminating, absurd contrast. In her video interview from May 29, Rahman makes the point herself, drawing a bright line between destruction of life and of government property. Her lawyer, Paul Shechtman, interprets the events of that night the same way. Mattis and Rahman approached “a vehicle that was empty and abandoned and not near a lot of people,” he says. “It was parked on the road, badly damaged by prior incidents. It had a real quality of saying ‘Fuck you’ to the police. If what they had done was write something on the police vehicle that was abandoned, you could say, ‘Get control of yourself. You’re a lawyer.’ This was one step further down the path but motivated by the same sense of frustration and anger and the sense of This never stops.” He adds, “I haven’t found anybody yet outside of the people who brought these charges who think that 45 years is an appropriate sentence. Or ten years. Or five years, given the background of these people, given the damage that wasn’t done.”

Mattis and Rahman’s friends, many of whom are career activists, set to work during the early-morning hours of May 30. They called one another. They called other lawyers. A friend brought granola bars and water to the precinct house and begged the officers out front to give them to their friends. They reached out to the people they knew at the Federal Defenders of New York, which provides free representation to people charged with federal crimes, and reached out to everyone else they knew, too. Because despite their social connections and impressive résumés, Rahman and Mattis had, in fact, no money. Bail was set at $250,000 each and was guaranteed by their relatives and friends (the ones who worked in the private sector or in big law). On June 3, Rahman, back at home, went to a Zoom meeting at work.

But the prosecutors moved to keep Rahman and Mattis detained — an indication of how aggressive they intended to be — and on June 5, a three-judge panel in the Second Circuit agreed, sending Mattis and Rahman back into the detention center. Each was placed in isolation because of coronavirus guidelines, in effect giving them a stint in solitary confinement. They were held for nearly three weeks, until June 23, when a different panel of judges in the Second Circuit heard arguments by Shechtman and Sabrina Shroff, Mattis’s lawyer. The government had argued that Mattis and Rahman should be denied bail precisely because of their abundant social support, stable jobs, and clean arrest records; if they could commit such a grievous act despite all this stability, the argument went, who was to say they wouldn’t do it again? In an amicus brief, 56 current and former federal prosecutors argued that this was hogwash: If it held, they said, it could be used to deny bail in every case. Eventually, the Second Circuit agreed.

Since June 30, Mattis and Rahman have been home, wearing GPS ankle bracelets and seeing approved friends. The legal strategy, if it can be called strategic, is to dawdle until November, or even January, in the hope that a less politically pugnacious Justice Department will be ushered in.

Rahman is taking it day by day, receiving occasional calls from her Sufi spiritual adviser, praying with him, trying to stay in the present moment and focus on gratitude. Her mother keeps saying, “Focus on today, focus on today, focus on today,” according to a friend who saw them recently. Mattis, though, is thinking about what he wants to do next. “I gave him a really, really long hug,” says Iheoma of his recent visit. Mattis being Mattis, he was hashing over all his future options, this or that, given the likelihood that he will be disbarred. “And I was like, ‘I don’t know,’ ” Iheoma says, “ ‘maybe you could run for mayor one day.’ ”