Tate-Pilled

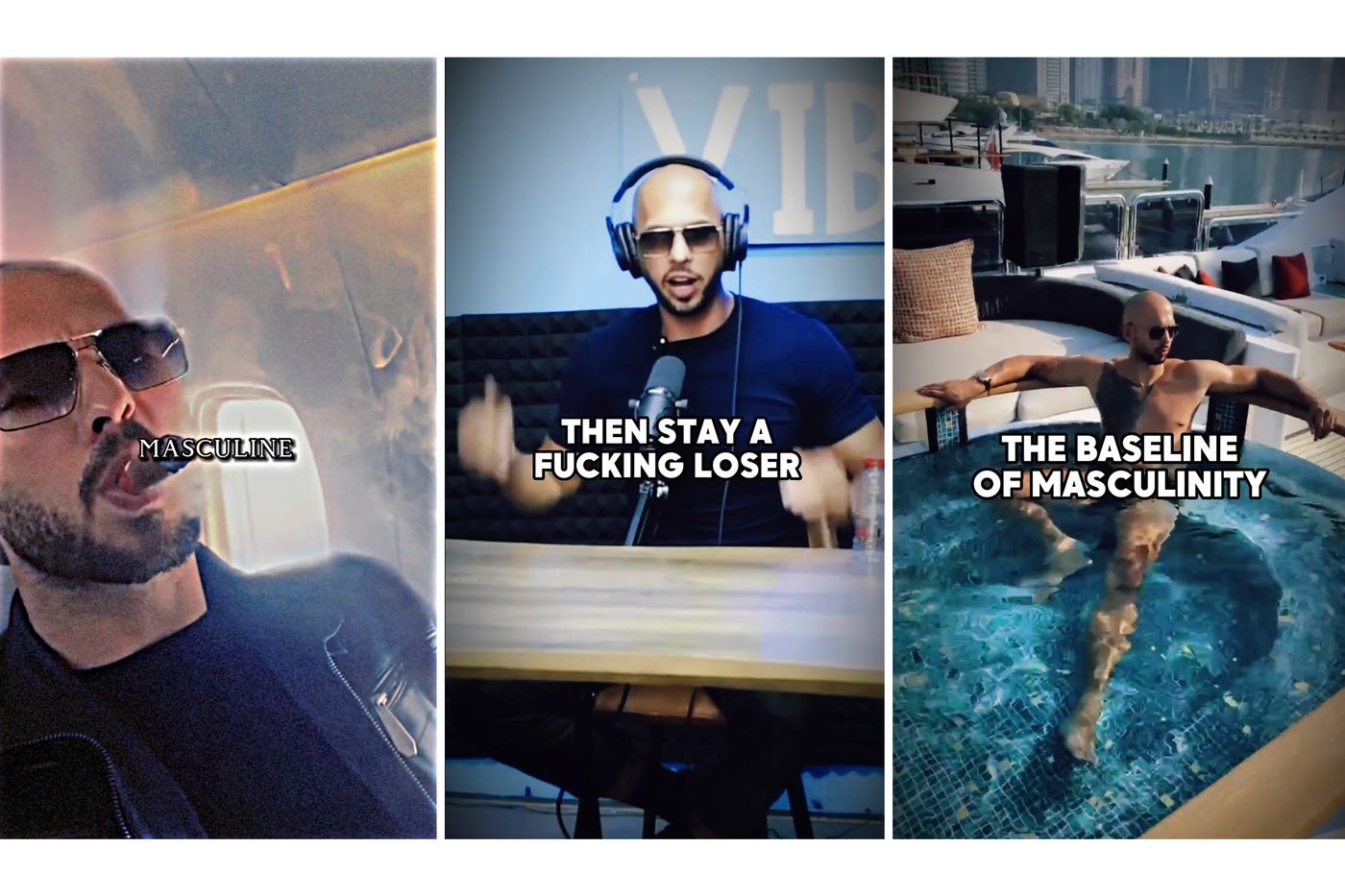

That the boys remember is not one particular meme or video, but how Andrew Tate conquered their TikTok “For You” pages seemingly overnight. Without warning last summer, the former kickboxing world champion obliterated the NyQuil-chicken recipes, the Minion mobs, the Amber Heard mockeries, and every other trending brainworm. It’s probably not an exaggeration to say that if you were an American male between 12 and 20 with a TikTok account, “Top G,” as he calls himself, was an unavoidable presence, uploaded by megafans, then reposted and shared, stitched and duetted by scrollers, critics, and stans. By the end of 2022, #AndrewTate had been searched on TikTok 22 billion times.

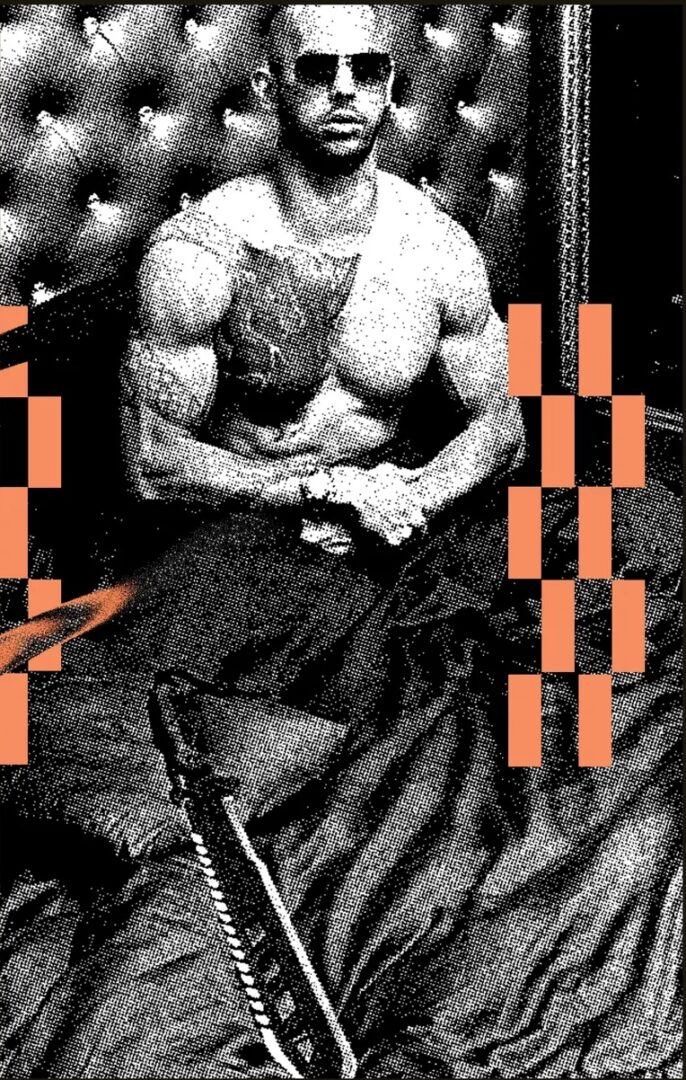

The boys clicked on Tate because of his striking appearance — the glossy shaved head, the physique “yoked as fuck,” as the comedian Noel Miller observed on The Tiny Meat Gang podcast, with a menacing cobra in a devil’s mask tattooed on his chest. But they stayed for the ostentatious, outrageous masculine display: the machetes and cigars, the diamond watches, the Bugattis and Lamborghinis, the obscene piles of banded cash like a scene out of Scarface. One viral TikTok showed Tate poolside in orange swim trunks and velvet slippers, chomping a cigar while demonstrating his nunchuck technique. In another, on a private jet, Tate taunts his brother, Tristan, for eating sushi. Eating “rice in a circle” will make men weak, Tate says, whereas his meal, fried chicken, makes men strong. “You know who eats sushi? Little fucking soy boys. Little fucking Democrats.”

His fan base lived all over the English-speaking world, and it seemed to defy race, class, and religion. Tate appealed to the rural American pro-gun constituencies and to the anti-vaxx, anti-mask communities; he appealed to schoolboys in Sydney and working-class immigrants in the U.K., to young rideshare drivers and to jet-setting tech bros. Tate’s saturation was so complete that he reached into the blue villages of New York City, where many boys in their bedrooms found his rude and ruthless evisceration of every sacred liberal value hilarious. Feminism, environmentalism, gluten intolerance, literature, Harry Styles, Lil Nas X — Tate assaulted all of these with pejoratives the boys themselves knew not to use. Outside of school, they took pictures posing like him, their fingers laced together with their index fingers pointed like steeples; they made machete jokes in the group thread and listened to Tate in the gym; in private, they said, “He’s my guy. I love him. He’s so smart; he’s so relevant.” But when girls were around, the boys knew to keep quiet. Girls hate Tate.

Boys entered Tate world through his most arresting clips — including those that suggest a violent hatred of women. In one TikTok that circulated untold millions of times, he describes what he would do as a pimp if a woman accused him of cheating: “Slap slap grab choke shut up bitch sex,” he said. The true stans lingered online for hours. One teenage viewer calculated he had watched between 48 and 56 hours of Tate; another laid up with an injury watched Tate nonstop all summer. “My friends would be scrolling for hours and hours and not saying a word,” says Spike, 17, a high-school senior in Brooklyn. On YouTube, fans found the original interviews, and podcasts that had been shredded into TikToks, as well as higher-concept video essays in which Tate puts forth his views on the struggles of young men, talking about the fear of competition, the allure of gaming, the rise of depression and suicidality. Tate upholds mental discipline and physical toughness as the ways to conquer the malaise, saying things like “If you cannot control your own mind, then you are just a feather in the wind.”

Above all, Tate talks incessantly about The Matrix, a dog whistle for incels and red-pill adherents, which in Tate’s version means the humdrum workaday world of wage slavery — of formerly proud men controlled by big business and governments, who never get ahead and whose feminist wives refuse them a blowjob at the end of the day. Freedom, Tate asserts, is attained by living his way: by getting strong and rich and becoming a G.

Christian, who is 12 and has filters on his phone set by his parents, encountered Tate through a YouTuber named Sneako who occasionally shows up in Tate’s videos as part of his crew. Sneako achieved notoriety through a video in which he asks Black people whether it’s okay for white people to use the N-word and then offers white people $1 to say it. Christian goes to a public school in a suburb of New York. He had a horrible time in sixth grade, he says, zero friends, just coming home after school and playing Roblox, and he credits Tate with changing his life. “Mind-set is everything,” Christian tells me, echoing something he learned from Tate. “If you live in the mind-set Oh, I’m depressed, then that’s probably what’s going to happen. If your mind-set is focused on positive things, then the depression is going to be a lot less.” When seventh grade came around, Christian joined the wrestling team, and he is considering taking up soccer and kickboxing. He feels popular. Now instead of playing video games, Christian says, “I like to train. I like to work out. I like to have fun with my friends.” When he grows up, he tells me, “I want cars and big houses. I have to be realistic. I’m probably not going to get cars and houses if I’m not determined.”

In August, Tate got removed from TikTok, YouTube, and the Meta platforms for hate speech. He had compared women to dogs and children. He said he preferred to have sex with 18- and 19-year-olds because they’ve “been through less dick.” He even appeared to endorse sexual slavery, once insisting on the Dave Portnoy podcast that a woman in a relationship “belongs” to the man, “and the intimate parts of her body belong to him.” The deplatforming made mainstream news, and in that moment Tate came out of the boys’ bedrooms and into the bright light of the kitchen, alerting many parents to him for the first time. Progressive-minded parents panicked.

They couldn’t comprehend how they could have been so oblivious to this misogynistic right-wing macho man who had been living under their roofs for months. And they were flummoxed as to how their children could admire, even idolize, him, when they were consciously trying to raise them to be good and kind. They looked for causes: an absence of male role models, shifting gender norms, their own complicated marriages, the isolation of the pandemic, the ordinary agony of adolescence. Donald Trump. It felt, one parent named Ruby told me, like every social-media horror story. “It’s going to start with an elephant doing a dance and the next thing you know they’re signing up for alt-right neo-Nazi shit.” (Ruby, like every other character in this story, is pseudonymous. Most are white. Several of the kids quoted are the children of friends; a handful go to the same school.) Teachers’ groups and women’s advocacy groups decried his influence, saying Tate was glorifying abuse to school-age kids, and memes mocking Tate began to circulate. The stans dug in, amplifying his visibility. The last week of August 2022, Andrew Tate was being Googled more often than Trump, Kim Kardashian, and the queen of England combined.

Christian regards the Tate panic as a misunderstanding: “He makes a lot of jokes, and people take him out of context.” He sees Tate as “a little misogynist but not much much.” For Halloween, Christian dressed up as Tate, even shaving his head, “and I went to the most fun party of my life.” His mother, who hadn’t really dialed into Tate, helped him with the costume, but she wouldn’t let him have a cigar.

In December, Tate, who is 36, and his younger brother, Tristan, were detained near Bucharest, Romania, where they had been living in a villa, and placed in jail as authorities investigate them for suspicion of organized crime, human trafficking, and rape. But Christian is sticking with Tate: “He’s saying there’s no evidence against him, so I’m taking his side for now.”

As a young kickboxer in the 2010s, Tate learned that being a good fighter wasn’t enough. He had to put on a show. Back then, he called himself King Cobra and played the pretty but anguished assassin. (“Pain,” Cobra said during one post-fight interview. “It’s all I know.”) Top G is his current persona, a two-dimensional man, all muscles and priapic display, apparently impervious to human vulnerability. Tate identifies with the pantheon of boy legends. He compares himself to Batman and James Bond and references the wisdom of Bruce Lee. He is a maverick like Steven Seagal but with the corrupt hubris of Michael Corleone. He is a character, but he is also Tate, and in interviews, he claims that he’s joking and that he’s dead serious. In the viral clips, he sits before the mic wearing dark glasses, a black T-shirt, and a white blazer so snug his biceps are visible, answering in his bombastic, unremitting style like an assault rifle. So exaggerated is his performance of boy-world archetypes it seems almost like a send-up.

Tate also inhabits the very online world of men’s men, and he alludes to, insults, praises, and goes on the podcasts of those characters, too. The fans understand Tate in relation to them. Unlike Joe Rogan, Tate is a terrible listener. He is more of a heel than the pretty-boy boxer Logan Paul and less fratty than the Nelk crew. He spouts alt-right conspiracy theories about vaccines, masks, and women like his acquaintance Alex Jones, and he annexed the universe of gamer nerds by attaching himself to the Twitch streamer Adin Ross. He is a high-speed bellicose debater and interrupter like Ben Shapiro and, like the Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson, seemingly concerned about the psychic pain of young men. Yet the boys see him as more charismatic and aspirational, so he becomes exemplary to them in a way the others are not.

A small subset of boys and young men encountered Tate early, but the majority were unaware, so when he appeared on their “For You” pages in 2022, he seemed to have come out of nowhere — a superhero move. He tripped wires in their brains that had been laid down in childhood, and they recognized him. One told me he seemed like a cross between Thor and Patrick Bateman of American Psycho.

The boys weren’t put off by Tate’s cartoonishness. It was part of the appeal, and the fans in liberal households trusted that they were intelligent enough to weed out the valuable content from the misogyny and the comedic hyperbole. And Tate seemed to be presenting truth — facts — that the boys felt they weren’t hearing anywhere else. They were growing up at a time, they say, when it was impossible to envision what kind of straight man to be. LeBron was amazing, but he was a one-off, and the other trending male idols were impossible to emulate — like Harry Styles and Timothée Chalamet with their “politically correct but also not a simp, but also attractive and manly, but also not crazy and misogynistic” presentation, as one boy puts it. Then Tate came along and told the boys that it was good to be men and to want the things men have traditionally wanted. When he said, for example, “There are millions of young men out there who just want to grow up, go to the gym, get strong, be respected, have a beautiful girl and a sports car,” many boys felt the relief of recognition and something like pride. It was so straightforward.

And then Tate went further, egging them on, reminding them of other young men who “don’t want to wear makeup, who don’t want to take transgender blocking drugs, who don’t want to assign themselves any kind of feminist ideas.” He told the boys they were naturally programmed to want to acquire wealth and to compete to become what he calls “top-tier men” and that, as men, they were evolutionarily superior to women — more rational, better drivers, better leaders. Most of the fans knew better, but that was the funny part: They concede it gave them an illicit boost. If you’re a teenage boy and feeling misunderstood, “it’s helpful to hear I’m meant to be stronger than a lot of my peers, that I’m meant to be better, bigger,” says Jacob, a senior at a public high school in Brooklyn. “It’s appealing to think that you’re more rational than 50 percent of the population, just because.” When he was about 13, he spent 18 months down the alt-right rabbit hole before he pulled himself out. Jacob thinks Tate’s influence on young men is “horrible.”

Dylan, who is 17, attends a different public high school in Brooklyn. He is good looking and popular, and his high-achieving girlfriend is too. But Dylan struggles to stay organized, and he is, as he puts it, “doing shit in school.” He feels desperate, sometimes, about his future. Dylan wants to be able to afford nice things — headphones and high-end fashion and jewelry — and he wants to be more than middle class, yet he can’t envision what adulthood will look like or how he’ll get there. He first saw Tate last summer on TikTok, he thinks because he was already watching self-help videos by Peterson, and he liked Tate instantly. Tate talks about heartbreak and trauma as the necessary struggles of manhood, and he seemed to understand Dylan’s problems because he’d lived through them too.

“I feel like, in general, in mass and mainstream media — this is definitely a very controversial thing to say — masculinity is being painted in a very bad light, then this guy comes along who’s very masculine and he’s inspiring the youth,” Dylan tells me. He wants to be more productive in his life so he can feel less lost, he says, “and then I turn on TikTok and there’s Andrew Tate saying, ‘You have to work as hard as you can, and if you just work on your goals, you’ll achieve them.’” Other influencers aren’t giving point-by-point constructive advice, Dylan told me. “Tate will say, ‘Why are you watching me? Go do something productive,’ and I’ll go do whatever I’ve been procrastinating, like my homework,” he says.

Dylan consumed Tate mostly on TikTok but also YouTube, where he found Tate’s motivational videos — like Fix Your Mind, a glossy six-minute montage of Tate clips and stock footage that has the digestibility of a pharmaceutical ad. At its start, Tate is the young kickboxer, exhausted and vulnerable. Then the mood changes and there’s the adult Tate speaking to the camera: “You’re either a disciplined individual or you’re not a disciplined individual.” The background music, electronic and tuneless, crescendos, and Tate hollers, “When I had nothing, I couldn’t be distracted.” There’s a shot of him doing pull-ups. In the final two minutes, viewers behold all the freedoms money can buy: fast cars, Scotch, formal waiters pouring sparkling water. (Despite Tate’s frequent references to girls as prizes, women almost never appear in these videos.) “Walk the fuck up,” he says, “and be the man.”

One day, Dylan’s mother found a piece of notebook paper in the dining room. On it was written a Tate-inspired productivity plan. At the top, it said, “You will be healthy for 1 week.” Then a list of mantras: “Once you have a healthy body you will have a clear mind.” Then: “Once you have a clear mind then your priorities will fall into order.” Ending with: “Wake up tomorrow and do something productive.” She posted it on the fridge.

Dylan can’t say that Tate has had much of an effect on his anxieties about his future — what he calls the “long-term stuff.” His mother says his grades have risen, but she thinks that’s owed to the positive influence of his girlfriend.

Photo: MIHAI BARBU/AFP via Getty Images

Tate learned his barbarism at his father’s knee. The first child of Eileen and Emory Tate, Andrew spent his earliest years in Goshen, Indiana. His mother is English and white; his father, an Air Force linguist, was a trailblazing Black chess player with the rank of international master, an erratic and brilliant player whose competition name was Extraterrestrial. In Tate’s telling, Emory was a rough man — a drinker, gambler, and womanizer who spent months at a time away from the family to play chess. Andrew idolized him. One time, when Andrew was about 6, Emory returned after more than a month away. He and Eileen immediately got into a row and Emory turned and walked out the door, saying to Andrew, “When you’re older, you’ll understand. Your mother won’t shut up.” Tate chuckles and raises his eyebrows. Incredulity at the memory passes across his face, then he changes the subject.

When Tate was around 11, Eileen moved with the children back to the U.K., where she could more easily access the government’s help. The family lived in a council estate an hour north of London, and Eileen took a job washing dishes for $400 a month. Soon after the move, Tate told an interviewer, Emory came to visit, and in preparation, Eileen took Andrew to get a haircut. She wasn’t satisfied with it, and when Emory walked into the house, Andrew echoed his mother, complaining about the haircut. “What the fuck are you doing?” Emory hollered at Eileen. “You raising my sons into bitches?” Then he took Andrew to a barber and made him shave his head. His parents eventually split officially, and Emory died in 2015. Tate continues to uphold his father as a man of honor and principle.

As a poor kid in the council flats, Tate would see men driving Ferraris and become enraged that they seemed to be flaunting possessions he could not afford. Things would be different when he became “rich rich.” From Emory, the chess master, Tate seemed to have learned to see human existence as a battlefield with winners and losers, men and bitches, kings and “brokies.”

When Tate decided to quit kickboxing and get rich, he took an inventory of his assets. What he had, he said on venture capitalist and crypto booster Anthony Pompliano’s podcast in 2021, were girlfriends. When you’re traveling the world on the kickboxing circuit, he explained, you can hook up with the “ring girls.” So as he told it, he had five girlfriends in different countries and said he was thinking, Maybe I could open a strip club, be a pimp, and, you know, be a gangster about it, when he came across a webcam ad. It read, “Hot girls want to talk to you now,” he said, “and I clicked on it because I thought, I have hot girls.”

Pompliano did the interview before Tate became huge, and you can hear it in Tate’s voice; he’s looser and more transparent. He invited all five women to his home to persuade them to help him launch a webcam business, and two agreed. From there, Tate and Tristan built a business that, he said, eventually grew to 75 girls in four locations talking to men online for money.

The women lived in group houses run by Tate. The way it worked, the brothers later told a reporter in the U.K., was that a customer would pay $4 per minute to message live with an attractive girl, and after some chitchat, the girl would tell him how she needed money because her grandma was dying or her dog was sick or she was behind on college loans. “It’s a total scam,” Andrew told the reporter. The girls used fake names, and their stories were made up; they typed on a keyboard disconnected from the computer, and Tate or another person off-screen would message the customer as the girl, saying what they knew the man needed to hear. Tate would take half of whatever the man paid her.

He claimed he was making the women rich. “Women have to want to work for you. Women have to want to obey you,” he explained. Tate compares himself to someone who “uses sex as a weapon” and a “reward.” He wouldn’t be sleeping with all the women, but “you’re obviously sleeping with some, whatever.”

“Wait,” Pompliano interjected. “You can’t say that offhand comment and just keep going.” Tate clarified. He was probably sleeping with 65 percent of his employees. They wanted to have sex with him, he said. “It’s like the adage of the woman at the office liking her boss. You’re her boss. She’s naked in your house. You’ve made her millions and millions; you’ve got a Lambo out front. You’re the big G.”

In 2016, Tate appeared on the U.K. version of the reality show Big Brother for five days before the producers removed him. The reported reason at the time was the emergence of a sex tape that shows Tate hitting a woman with a belt. In the tape, Tate, kneeling in bed fully clothed, demands that the woman say she loves him before he pounces on her and begins thrashing her. (The woman later made a video saying it had been “pure game” and they were still friends.) Seven years later, the real reason for Tate’s removal would come to light: At around the time of the Big Brother taping, one of the women he hired had charged him with rape and another with assault. Ultimately, the police couldn’t make the case, but the women’s accounts, reiterated in a Vice investigation published this year and including descriptions of choking, are harrowing. The same year as the Big Brother scandal, Tate and Tristan moved to Romania. The webcam business is big there, Tate told Pompliano.

Tate founded his next venture, Hustlers University, in 2021. HU was an uncredited online “school” where boys and young men paid $50 per month to learn the skills that would enable them to escape “the Matrix” and put them on the path to becoming G’s (it was rebranded as the Real World in 2022). HU’s most popular courses were in copywriting, but it also offered courses in drop-shipping, crypto investing, freelancing, and personal finance. “Professors” — some of whom did double duty in Tate’s entourage — motivated their students by calling them losers and exhorting them to do push-ups. On HU’s message boards, students sought advice — about dating after a breakup or grieving the loss of a beloved dog or feeling the urge to quit school. Boys who said they were as young as 14 answered questions about payment processing.

What HU did for Tate was to build an enormous international sales force of young men who paid to work for him. In HU’s marketing course, students learned how to edit and repost clips of Tate on social media with an affiliate link; each time a new student subscribed to HU, the OG poster got half of a first month’s commission, or $25. A fair amount of Tate content already existed online, but in late 2021, Tate started to travel the podcast circuit in earnest, giving his boys something new to sell. In December, he went on Fresh & Fit, a dating show, and called women “ultrafeeble,” and then on Your Mom’s House, a podcast by Rogan’s former sideman Tom Segura and Segura’s wife, Christina Pazsitzky. There, Tate said he had no use for a challenging woman. “All men want robots!” he insisted. “There’s no such thing as too submissive.” He seemed to be laughing, and his hosts, off balance, laughed along. By the spring of 2022, Tate content was starting to be seeded everywhere, and because the Tate stans were mostly Gen Z, they defaulted to posting on TikTok. By July, HU had over 77,000 members, and the world of boys seeing Tate grew even bigger.

The TikTok algorithm seems able to predict users’ appetites, so the boys might have encountered Tate any number of ways — by searching for crypto, Bugattis, or Tae Kwon Do or by researching nunchucks or get-rich-quick schemes or chess. But they also might have discovered him by wandering distant paths. Jacob, the son of a former community organizer, watched the Star Wars movie The Last Jedi when he was in middle school; he had been an ardent fan, and he hated the film because he felt Disney had turned Luke Skywalker into a joke. So he went to YouTube for some critical reads, and the next thing he knew, Ben Shapiro, a Star Wars nerd, was being served to him on his feeds. Shapiro was arguing that the SJWs (social-justice warriors) at Disney were determined to feminize the franchise that had long been what he considered a meaningful “little boy’s property.” These arguments appealed to Jacob because he was feeling terrible and angry, so for a time, he went down the alt-right vortex, consuming hour after hour of -Shapiro and Owen Shroyer of InfoWars. “Hate begets hate begets hate,” Jacob tells me. By last summer, he’d stopped watching, but he wasn’t surprised when his “For You” page served him Tate.

In 2019, in an opposite corner of the internet, the YouTuber Natalie Wynn made a 30-minute video titled Men. Wynn is a transgender philosopher and commentator on gender politics, and she posted the video on her channel, ContraPoints, which has 1.65 million subscribers. In it, she lays out with surgical delicacy the ways she thinks feminists have failed to address what some now call “the masculinity crisis.” Wynn is a scholar of alt-right men’s groups and is sympathetic to the world of feminists who regard the suffering of men (in particular straight white men) as a nonstarter given the manipulators online and in Congress who persuade men of their disenfranchisement at the hands of feminists in order to amass more power for themselves. Not to mention the incontrovertible, everyday fact that the men who have historically held power continue to remain in power. But in Men, Wynn gently asks her progressive viewers to consider the possibility that men’s-rights activists’ concerns contain a nugget of truth: that the suffering of men is real, especially among those who were never high on any kind of ladder. Much feminist theory accounts for this, but many online feminists don’t. “Maybe the average man is also oppressed by the system the feminists call patriarchy,” Wynn says.

She describes a “genuine crisis of male identity” caused by the decades-long shake-up of cultural gender norms. “The traditional protector-provider role of men is being replaced by a more equal and undefined gender dynamic,” she argues, and this loss of purpose has contributed to higher rates of depression, anxiety, suicidality, and loneliness in men, which is not ameliorated by well-meaning liberals perpetually calling them “toxic.”

“I think a lot of feminists have failed to imagine the ways that being treated as invisible or dangerous can also kind of suck,” she says.

At the end of the video, Wynn calls for a new, positive model of manhood created by men in conversation with men. But out in the world, this kind of talking is nonexistent. Online, there’s yelling and dunking. And at school, where America’s boys and young men spend their days, the earnest public statements about open communication and mutual respect are countermanded by anxiety and exhaustion among administrators and teachers, as well as growing pressure to show results while avoiding claims of harassment and bullying. So when a student raises a thorny topic in class — Why can’t I use this slang? Why can’t I wrestle with my friends in the hall? — a stressed teacher’s impulse may be to change the subject and move on.

Kids sniff out adult hypocrisies, and they withdraw. Dennis, a public-high-school teacher living in Brooklyn, calls the atmosphere in his mostly white classrooms “the New Victorianism.” Everyone wears baggy hoodies and sweats. It’s the fashion, as if no one wants to risk gender or body presentation. But it’s more than that. Dennis believes children live in two worlds, and the real world is “constantly hidden” on their phones. They are anxious and inhibited, fearing censure or punishment, about saying what they really want or think, and so they share their unmasked selves on finsta with a small, curated group. School, which used to be a noisy place, has become quiet. Timothy, a public-high-school teacher in a majority Hispanic and Asian community in Queens, echoes Dennis. He says that in school, boys complain to him, “I can’t be me.”

Dennis is an advocate for boys, and he believes that schools are a magnifying point for society’s culture of shame and that some kinds of shame fall disproportionately on them. He has been present when adults at school — parents, teachers, or administrators — talk about boys as “inherently dangerous,” reflexively wanting to “contain” or “control” them for the smallest hallway infraction so that a minor conflict doesn’t blow up into a big one. These adults talk about “safety” and “accountability” — ostensibly to protect other students, but really to protect themselves from legal or reputational consequences. Dennis believes that hardly any straight boy has the language to speak truthfully about how he envisions romance, dating, or sex because “they know if they say it aloud, someone will censure them or say they are encouraging rape culture.” So they confess their dreams to him in private in his office. And what they say is “I want to make a lot of money. I want the life I want. I want to be free.” Dennis adds, “It feels very Bret Easton Ellis. Empty at the center but all about the performative nature of being a male.”

Even at well-resourced schools with robust curricula for talking about identity, the conversations aren’t striking a chord with some of the kids. Spike, who is 17, describes the eye-rolling among his peers when they’re forced to attend another seminar or symposium on systemic racism, microaggressions, misogyny, white saviorism, gentrification, toxic masculinity, or gender roles. Last year, for a social-justice day, the school created “affinity spaces for every single identifier,” he recalls. In the white-male affinity space, no one spoke. “Everyone sat around and played video games.”

Jacob has friends who consume Tate’s videos, and he’s noticed a change in them. Out of school and on the street, his friends relax, and “they can slip into something they might not have normally said, just casual remarks, jokes about women, the wage gap, how women should be in the kitchen.” It’s a kind of arrogance, or at least a misapprehension, to believe that you can take the good without the bad, two different boys told me. One put it this way: “They think they’re taking the valuable stuff and leaving the garbage. But I don’t think they’re successful. People are much more susceptible than they like to think they are.”

Most of the girls I spoke with have male friends or acquaintances who follow Tate. They’ve checked on Instagram. (Chloe, who goes to a public school in Madison, Connecticut, immediately unfollowed all of them.) The girls can’t attest to which came first, Tate or the rise in misogynist jokes, only that they seem to be part of the same thing: sexism under the cover of humor posing as irony. Maya, a junior, describes the “prank” videos that circulate on TikTok and private threads in which a boy makes a girl think he likes her and then films her mortification when he tells her it’s a “joke.” It’s the same with Tate. “When you’re following someone so closely and listening to so much of their content, that’s a lot of time to be spending on a joke,” Maya says. “These boys who go to these liberal private schools — on paper, of course, they would say that sexism is bad and misogyny is bad. But they contribute to the culture of it, and they can claim they’re innocent because they know it’s wrong.” When she wants to call them out on a joke, she tells me, she tries to be strategic. “You have to find a way to do it that’s not annoying or cautioning them.”

Valerie, another private-school student, sees there’s maybe some truth to the notion that as liberal institutions are “centering female voices, queer voices,” they aren’t extending sufficient compassion to boys. “The message is, ‘Let these other people talk. You’ve had your time,’” Valerie says. “And probably the boys think, I haven’t had my time. I was just born! I was going through puberty yesterday!” Adolescence is hard, she acknowledges. Emotions are high, and it’s easy to feel alone. “To feel that way and then to hear, ‘Your voice is not relevant to this conversation,’ I can imagine how young straight boys feel more isolated than they used to.” She pauses. “But the change is a net positive. I’m maybe not that sympathetic.”

Last summer, Ruby, a Brooklyn mother, began to be concerned about her younger child, Charlie. He had always been the more “masculine” of her two boys, into trucks and bulldozers instead of crafts. He was a persuasive debater and a competitive athlete. Then last spring, when Charlie was 14, he began to withdraw from his social group. He became “fixated on getting more muscular, stronger.” And he started talking about Top G, as in “Top G eats protein.” Charlie listens to a lot of hip-hop, and Ruby thought maybe Top G was a rapper.

As Tate was blowing up, Ruby made the connection and grew concerned — even more so when Charlie told her that Tate was being interviewed on Tucker Carlson and suggested they watch together. She and her husband said “no.” “I’m like a Brooklyn, far-left person. If Tucker Carlson interviewed Barack Obama, who’s probably my favorite person on earth, I wouldn’t watch that,” she says. Charlie tried to explain, arguing that his liking Tate had nothing to do with politics. His mom and dad held firm and threatened to remove TikTok from Charlie’s phone. They didn’t — there would always be Instagram and YouTube and Discord — and Ruby didn’t want to be that kind of parent, so she spent the summer listening to Charlie listen to Tate from the couch. It frightened her. Charlie had always been a “sweet, chill kid,” Ruby says, and now he was occasionally talking in a scary, unfamiliar way about how everyone around him was an NPC (a non-player character in a video game, an impotent cog) within the Matrix. He didn’t have friends, he said. He had “associates.” He started to spend less time with his friends who were girls. Finally, at the end of the summer, Ruby suggested therapy. Charlie eventually agreed as long as the therapist wasn’t, as he put it, “some Park Slope mom.”

The rest of left world discovered Tate in the final days of 2022. For years, he had periodically amused his fans by tossing Twitter bombs into the left’s sacred spaces, and on December 27, he tweeted at Greta Thunberg, the environmentalist, boasting about his collection of 33 super-cars and “their enormous emissions.” “Yes, please do enlighten me,” Thunberg commented. “Email me at [email protected].” Within two days, Thunberg’s tweet had 3.5 million likes, making it one of the most viral tweets of all time.

Two days later, Tate and Tristan were jailed in Romania. They purportedly lured women to that country, then persuaded or forced them to work for their OnlyFans operation, “transform[ing] them into slaves,” according to Romanian prosecutors’ documents viewed by Reuters. In these documents, a Moldovan woman accused Tate of raping her twice and an American woman said she had been kept in a house manned by armed guards, her movements tracked by video cameras.

(In addition to the accusations of human trafficking, organized crime, and rape, Romanian authorities said they are investigating the Tates for money laundering. The lawyer for Andrew and Tristan Tate did not respond to requests for comment, but asserted their innocence in interviews.) Two more women, also reportedly named in the documents as alleged victims, went on Romanian TV to deny they were victims. One showed the camera a tattoo that read TATE GIRL.

Since Tate’s imprisonment, his online presence has dimmed. The blue-zone kids aren’t really seeing him on their feeds. For a while they hollered “Free Tate” at school whenever the subject came up, but now they speak of him in the past tense. Charlie has distanced himself from Tate, and his mood seems lighter, his mother says. Tate continues to tweet and push out email newsletters, ostensibly from jail, and Tate accounts continue to live on Twitter and Rumble. His online school is still operational with 200,000 subscribers enrolled.

Back in December, Ruby thought Thunberg’s tweet was hilarious, and she tried to tease Charlie. “So your boy, he’s kind of the laughingstock of the internet,” she said. “He gave me this side-eye death stare,” she tells me. Charlie has never liked Thunberg. “He has always thought she was kind of a tool. I don’t know why. It’s always made me feel awful. I think part of it is, ‘I don’t want to be told what to do by some girl.’”