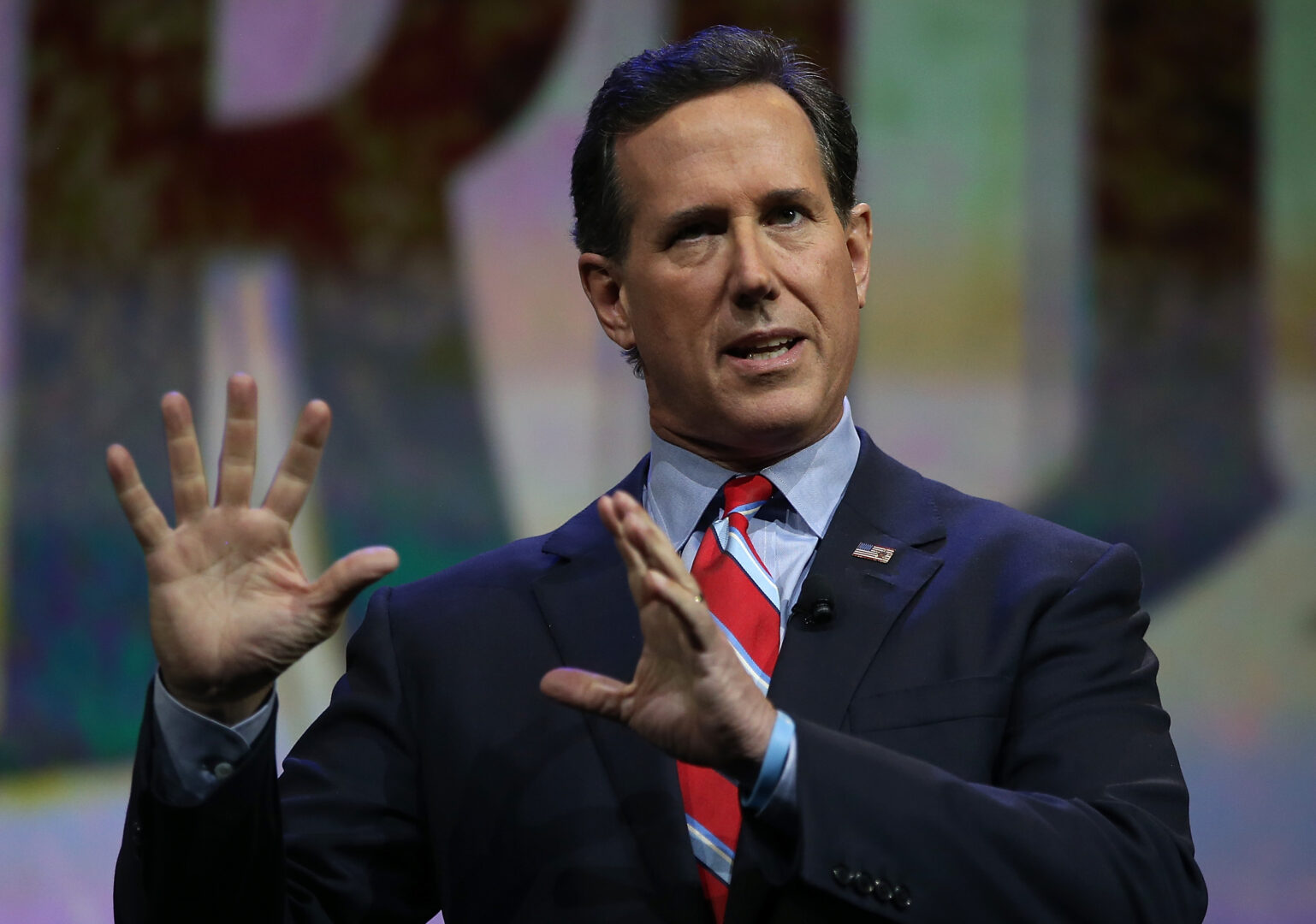

It’s impossible for some of us to understand why and how former senator Rick Santorum, who has zero qualifications to be president of the United States and whose positions on family and social issues are prehistoric, continues to survive and even thrive this Republican primary season. His victories in Alabama and Mississippi this week only further our astonishment.

This is not purely the blue-state bewilderment of urban elites. Even the Southern Republican establishment is surprised. I called Clarke Reed, who helped transform the South from a Democratic stronghold to a Republican one in the 1960s, to ask him what, exactly, Southern voters saw in Santorum. This is what he said: “Well, I really don’t know.”

And then he said, “I thought people would follow the Bill Buckley rule, and pick the guy who was going to get elected. Santorum is a good man. He lives a good life. But that doesn’t make him necessarily a good president.”

Finally, Reed settled on this explanation: “People are maybe voting what they believe, more than the practical side.”

That is the answer. The people who voted for Santorum in Tuesday’s primaries called themselves “very conservative” and also “born-again Christian.” They said they voted for him because of his “strong moral character.” These voters do not share with Santorum their religious beliefs, for Santorum is a Catholic and they are Protestants. But they share with Santorum what might be called a faith-based nostalgia: They believe that things were better before, they’re going to hell right now and only a strong commitment to Jesus Christ will turn America around.

Santorum is a traditionalist in all things. He is a traditionalist Catholic and has said that too many American Catholics observe “uninspired, watered-down versions of our faith.” He is a traditionalist husband and father, and is “traditionalist” (if you want to call it that) on constitutional interpretations.

Santorum voters are traditionalist Americans. They yearn for an age when America was run by white Christian men, when husbands went to work and wives stayed home and raised as many children as they could handle. (One Ohio blogger, explaining his choice for Santorum, called him “a real man.”) In that America, abortion was illegal and gay marriage was a schoolyard joke. In that America, everybody went to church.

Santorum and those who voted for him are looking back to a time when the United States “was free and safe and prosperous,” as he said in a victory speech this week, “based on believing in free people and free markets and free economy, and, of course, the integrity of family and the centrality of faith in our lives.” That last phrase refers, of course, to Roe v. Wade, but it also refers to a conviction (which Santorum shares with his fans) that God is real and intervenes to improve people’s lives.

This is the version of America described in “Game On,” a pro-Santorum song that has become a YouTube sensation. Sung in close harmony by two daughters of an Oklahoma pastor named David Harris, the song imagines a time “maybe for the first time since we had Ronald Reagan” where there’s “justice for the unborn, factories back on our shores.” “Yes,” the girls sing, “I believe Rick Santorum is our man.”

And in some ways, these voters’ concerns are justified. Their world did once feel better and more secure. Unemployment in Mississippi hovers near 10 percent, and in both Mississippi and Alabama, divorce and high school dropout rates stand above the national average. Mitt Romney — despite his five strapping sons and his professed love for “cheesy grits” — fails to convince these voters that he’s like them, not because he’s Mormon (though that’s part of it), but because he doesn’t share their determination to turn back time.

Romney, whatever his faults, likes to move forward. But conservative Christians’ sense of crisis is so deep, they don’t want to make a pragmatic choice. Romney wants to roll up his sleeves, organize some focus groups and apply some algorithms to their problems. What they want is to pray.

The vote for Santorum amounts to a Hail Mary pass, a last-ditch, desperate attempt to uphold values over the quotidian business of politics. It’s valiant in principle (though impossible not to note that the past that Santorum’s supporters idealize contains injustices too heinous and many to mention).

“You can’t go home again,” Thomas Wolfe said. Modernity is here, with all its progress and imperfections, and no matter how hard they pray, Santorum and his flock will never be able to turn back time.