A Woman’s Place Is in the Church

The cause of the Catholic clergy’s sex-abuse scandal is no mystery: insular groups of men often do bad things. So why not break up the all-male club?

Here they are, the members of history’s oldest and most elite all-male club, trying to manage what began as a domestic crisis. For decades, certain priests in America, Europe, Ireland, Brazil (and God knows where else) abused—raped or otherwise molested—children and teenagers not in the frescoed halls of the Vatican but in their own backyards: on camping trips and in cars, in dormitories and confessionals. Those few boys and girls confident enough to tell their secret whispered it to the women they trusted: mothers, aunts, grandmothers. Those few women brave enough to question authority or seek justice from the bishops were hushed up and shut down. In this case Jesus was wrong: the meek did not inherit the earth. They received pious and self-serving sermonizing.

“To be sure,” wrote Boston’s Cardinal Humberto Medeiros to one mother incensed over the sexual abuse of seven boys in her own family, “we cannot accept sin, but we know well that we must love the sinner.”

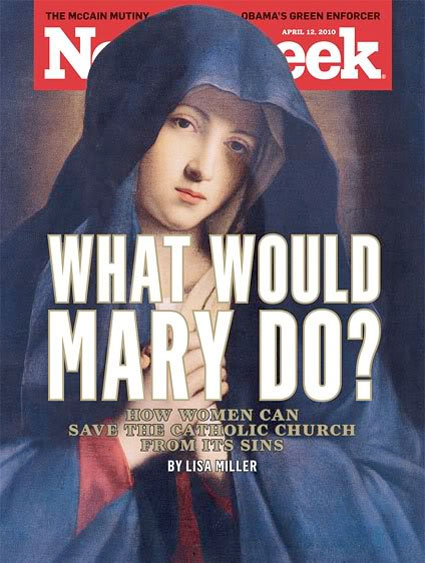

Even with a mother, Mary, at the center of the Christian story, the women of today’s church have found themselves marginalized and preached to amid the interminable revelations of the sexual-abuse scandals. Their prayers to the Virgin, protector of humanity, seem to have gone unanswered.

No wonder the men now charged with damage control face such a credibility gap, a sense that they—who read apologies from teleprompters—appear insufficiently aghast at the damage done. On Palm Sunday in New York, Archbishop Timothy Dolan condemned sex abuse from his throne in St. Patrick’s looking for all the world like a well-fed Fortune 500 CEO. A YouTube clip shows Cardinal Sean Brady of Ireland—where 15,000 children were abused over four decades—peremptorily dismissing calls for his resignation. After a New York Times story reported that Pope Benedict XVI (then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger) failed to defrock a priest who abused 200 deaf children in Wisconsin, the pope lashed out against the news media. Faith, he said, allows one not “to be intimidated by the petty gossip of dominant opinion.” Time and again, the pope and his surrogates fail to convince us of their grief.

The problem is not, as so many progressives claim, the fact of their celibacy. Nor is it their costumes—the miters and capes—though these vanities do serve as reminders of the great distance between the men with power and the people without. The problem—bluntly put—is that the bishops and cardinals who manage the institutional church live behind guarded walls in a pre-Enlightenment world. Within their enclave, they remain largely untouched by the democratic revolutions in France and America. On questions of morality, they hold the group—in this case, the church—above the individual and regard modernity as a threat. We in the democratic West who criticize the hierarchy for its shocking inaction take the supremacy of the individual for granted. They in the Vatican who blast the media for bias against the pope value ecclesiastical cohesion over all. The gap is real. We don’t get them. And they don’t get us.

By keeping modernity at bay, though, the men who run the Catholic Church have willfully ignored one of the great achievements of the modern age: the integration of women in the workforce and public life. In America, 50 million women work full time; in the European Union that number is 68 million. Within most mainline Protestant denominations, these battles over the professionalization of women were fought—and lost—half a century ago. In Denmark, Lutheran women were granted ordination rights in 1948; in the U.S., the first female Episcopalian priest was ordained in 1976.

But in the Roman Catholic corporation, the senior executives live and work, as they have for a thousand years, eschewing not just marriage, but intimacy with women and professional relationships with women—not to mention any chance to familiarize themselves with the earthy, primal messiness of families and children. Indeed, it seems the further a priest moves beyond the parish, the more likely he is to value conformity and order above the chaos of real life.

“I see [the hierarchy] as outrageously indifferent to the welfare of children,” says a fuming Elaine Pagels, professor of religion at Princeton. “For you and me this is hard to understand. It seems to us out of step with the world. But they don’t want to be in step with the world.”

Over and over I have heard mothers (and fathers) mourn. One parent in one room where a bishop was deciding the fate of an abusing priest would have saved countless families from a lifetime of misery. “It’s a pretty good guess that we would not be in this same predicament were women involved,” says Frank Butler, president of FADICA, a group of Catholic family foundations. “For sure.”

It is a reforming moment, then, a time for the men of the Vatican to take the wisdom of their own words to heart. The Second Vatican Council in the early 1960s was an effort to better integrate the antique church with the modern world, and its documents overtly address the changing place of women. “The hour is coming,” read the council’s closing documents, “in which women acquire in the world an influence, an effect and a power never hitherto achieved. That is why, at this moment…women imbued with a spirit of the Gospel can do so much to aid humanity in not falling.” Pope John Paul II expounded on the centrality of women to the church in his 1988 letter Mulieris Dignitatem (“On the Dignity of Women”)—even as he firmly reiterated six years later the church’s refusal to consider their ordination.

The chasm between the church’s stated principles and its functional reality yawns wide. In the U.S., 60 percent of Sunday massgoers are women; thus most of the contributions to the collection plate—$6 billion a year—are made by women. And yet the presence of women anywhere within the institutional power structure is virtually nil. The number of women who hold top-tier positions in any of the dicasteries, or committees, that make up the Vatican structure can be counted on one hand. Few women retain high-profile management jobs, such as chancellor, within dioceses. And though nuns dramatically outnumber priests worldwide, they are mostly so invisible that when a group of them speaks up, as they did recently on health-care reform, everyone takes notice.

Eight years after the Boston scandals, “it’s just men listening to themselves” on sex abuse, says Kathleen McChesney, the former FBI official enlisted to study and remedy the problem of sex abuse in American dioceses after 2002. “To my knowledge, there’s no woman in the Vatican who’s involved in sex-abuse issues.”

Kerry Robinson traveled to Rome last month to talk to cardinals about promoting more women. Executive director of the National Leadership Roundtable, a group of American businesspeople who hope to bring corporate best practices to the church, Robinson, together with a group of female colleagues, hoped to make a point. “A young woman looks at the corporate world and sees that she can reach the highest levels of leadership,” says Robinson. “She is frustrated at the lack of opportunities to live out her leadership in the church. The grave consequence of that is that the church becomes less and less relevant to women. And the consequence of that is that it becomes less and less relevant to her children.”

“It matters,” adds Robinson, “how the church is seen. Right now, it’s seen as sins and crimes committed by men, covered up by men, and sustained by men. To overcome that, the church has to absolutely include more women.”

Women aren’t a panacea, of course. History shows that women in power can be as ruthless and self-serving as men. And the mere presence of women does not, obviously, inoculate an organization against criminality or corruption—just ask Lynndie England, who smiled for the camera as she humiliated prisoners at Abu Ghraib. Moreover, it’s difficult to prove that the male-dominated atmosphere of the Roman Catholic Church creates a unique hothouse for sexual predators; and indeed, the majority of good priests throughout the world continue to care for the faithful. (The perpetrators in a few of the recent European cases have been women.) Researchers believe, in fact, that rates of abuse within the church probably compare with those of other denominations—and of youth organizations, schools, and families. It’s frighteningly high. “Surveys indicate that one out of three girls experienced an unwanted sexual approach from an adult before age 18,” says Margaret Leland Smith, a researcher at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, who analyzed the data from the U.S. sex-abuse cases. Among boys, she says, the rate is one in five.

Indisputable, though, is that the all-male Catholic hierarchy has responded to the crisis too slowly and—even after the revelations in the U.S.—in a way that has instinctively protected its own interests above those of the children. “The Catholic Church could have pulled these people any time they wanted and defrocked them,” says the Rev. Marie M. Fortune, a minister in the United Church of Christ and founder of FaithTrust Institute, a multifaith organization aimed at ending sexual violence. “You can make a good argument that part of the problem is the hierarchy, in terms of it being a boys’ club, an institution that is so ingrown and conservative and out of touch with people.”

Studies show what we intuitively know: without checks and balances, insular groups of men do bad things. History professor Nicholas Syrett, author of The Company He Keeps: A History of White College Fraternities, says studies suggest that 70 to 90 percent of gang rapes on college campuses are committed by men in fraternities. Obviously, he adds, important differences exist between the Roman Catholic hierarchy and college frats—”fraternity men are encouraged to have sex with lots of women. Clearly priests are not.” But in both cases, “men are encouraged to believe that they are in positions of power for a reason…I do think if the hierarchy of the Catholic Church doesn’t discipline these people because they are concerned about reputation, they create a space where those [abusing children] are led to believe that whatever they do is OK.”

Richard Sipe agrees. He is a former priest who has spent the past three decades researching the sexual teachings of the church and their effects on clerical behavior. “Clergy,” he says, “are a group that are very privileged in their own mind. They have a sense of entitlement. Think about it. What other culture do you know of that’s all male, theoretically and practically?”

Jesus, of course, said nothing about the role women should play in his future church. As the leader of a small and radical movement he invited all to join his band, including married women, single women, and prostitutes; and the Gospel accounts give women a special role. They are the ones who first encounter the resurrected Lord and report back to the men on this supernatural event.

Women probably worked in the early church. In his letter to the Romans, written in the late 50s (A.D.), the Apostle Paul writes of a deacon named Phoebe; a “fellow worker” named Prisca; and “workers in the Lord” Tryphena and Tryphosa. He even mentions an “apostle” named Junia—a fact so shocking to generations of scribes who imagined that apostles could only be men that they intentionally misunderstood Paul’s meaning. “Very, very frequently [Junia is] changed into a man’s name,” says Diarmaid MacCulloch, author most recently of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. “You get a sense that the early church is rowing away from women having positions of power.”

It would be a mistake, therefore, to view the first centuries of Christianity as any feminist heyday. Women were regarded almost universally as lower beings, over whom a good Christian man had to exercise control. “Our ideal,” said Clement of Alexandria in the second century, “is not to experience desire at all.” And—despite the fact that clerics and even popes were often married—women’s ability to arouse sexual desire in Christian men relegated them to the role of the temptress Eve, in cahoots with Satan. For women, celibacy was one way to gain any power in a man’s world; by emulating Mary, a woman might find independence and strength.

By the 12th century, the separation of men and women in the church was complete. Clerical celibacy became mandatory in 1139, and in the great universities of Europe, where Christian intellectuals were establishing the foundations of modern philosophy, math, astronomy, science, literature, and theology, women were excluded completely. The only way thereafter for a Christian woman to gain prominence was as a prophet or a mystic, observes MacCulloch—and then her brethren might regard her as cracked.

One more brick, and the Vatican clerics would shut themselves off from their faithful for good. Kevin Schultz, a historian at the University of Illinois at Chicago, explains that Rome objected—strenuously—to the individualism that led to the French and American revolutions. In reaction, Catholic intellectuals revived some of the ideas of Thomas Aquinas, especially his insistence on holding the community above the individual. The preeminence of these ideas essentially formed an “opposition to what the church sees as modernity,” explains Schultz. “It creates us-versus-them. There becomes this level of secrecy. The popes become much more powerful.”

No explanation better illuminates today’s great disconnect between all the pope’s men and the progressive faithful. In a world where the whole really matters more than individual parts, a rigid—sometimes brilliant, sometimes mean-spirited—morality reins. This elevation of the church above all things explains how an institution dedicated to serving the sick and the poor might also refuse condoms to those at risk for AIDS. It explains how an organization committed to families could deny birth-control pills to mothers. And it explains, sadly, how a bishop faced with a pedophile in a parish might decide not to call the cops.

To break the old habits of insularity and groupthink, the embrace of modernity that started with Vatican II must begin anew. “I want to throw open the windows of the church so that we can see out and the people can see in,” said Pope John XXIII of that effort. The first, and perhaps easiest, place to start is with women.

More than 60 percent of American Catholics support the ordination of women, and though traditionalists insist that’s a pipe dream, realists think otherwise. With priestly vocations in steep decline in the U.S., and women running 80 percent of parish ministries, female priests seem an inevitability. A small group of about 100 renegade women have already been ordained “by a bishop in good standing,” says Eileen McCafferty DiFranco, who is one of them. Though excommunicated, DiFranco remains unbowed. “Jesus never said only men can be priests.”

In the U.S., reported incidents of sex abuse in Catholic dioceses are dropping, thanks largely to the work of McChesney and her team. Now every American diocese must establish an advisory board on sex abuse, a group professionally and personally concerned with the welfare of children. McChesney believes these advisory boards should be replicated in dioceses worldwide—and at the Vatican. “Benedict needs to establish a group that is not just clergy. He needs an advisory board of people who are expert in child abuse, in investigative issues, in problem solving. You need the involvement of lay professionals.” If these people are women, so much the better.

On her diplomatic mission to the Vatican, Kerry Robinson had another, more spiritual goal. Over the years, stories from the Gospels and the Old Testament about women have slowly disappeared from the Sunday lectionary, the scheduled Bible readings that massgoers hear. Robinson gently brought this to the cardinals’ attention and found that some hadn’t noticed the stories were gone. “It’s all men, all the time,” says Robinson. “They go to mass all the time, they don’t distinguish, they don’t think of it from the perspective of a woman who goes to mass on Sunday.” Mary, the mother of Jesus, was human. A traditional girl, she made the best of an extraordinary situation and then watched, stoically, as her child suffered. This is a universal story. If the stories of the women and girls of the Bible aren’t told, then mothers and daughters will stop seeing themselves as part of the Body of Christ. They’ll walk away. And they’ll take their children with them.