In 1981 Barack Obama was 20 years old, a Columbia University student in search of the meaning of life. He was torn a million different ways: between youth and maturity, black and white, coasts and continents, wonder and tragedy. He enrolled at Columbia in part to get far away from his past; he’d gone to high school in Hawaii and had just spent two years “enjoying myself,” as he puts it, at Occidental College in Los Angeles. In New York City, “I lived an ascetic existence,” Obama told NEWSWEEK in an interview on his campaign plane last week. “I did a lot of spiritual exploration. I withdrew from the world in a fairly deliberate way.” He fasted. Often, he’d go days without speaking to another person.

For company, he had books. There was Saint Augustine, the fourth-century North African bishop who wrote the West’s first spiritual memoir and built the theological foundations of the Christian Church. There was Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th-century German philosopher and father of existentialism. There was Graham Greene, the Roman Catholic Englishman whose short novels are full of compromise, ambivalence and pain. Obama meditated on these men and argued with them in his mind.

When he felt restless on a Sunday morning, he would wander into an African-American congregation such as Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. “I’d just sit in the back and I’d listen to the choir and I’d listen to the sermon,” he says, smiling a little as he remembers those early days in the wilderness. “There were times that I would just start tearing up listening to the choir and share that sense of release.”

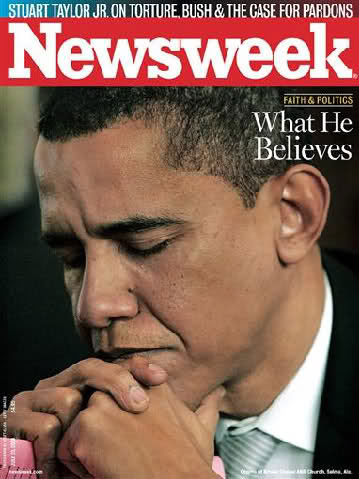

Obama has spoken often and eloquently about the importance of religion in public life. But like many political leaders wary of offending potential backers, he has been less revealing about what he believes—about God, about prayer, about the connection between salvation and personal responsibility. In some respects, his reticence is understandable. Obama’s religious biography is unconventional and politically problematic. Born to a Christian-turned-secular mother and a Muslim-turned-atheist African father, Obama grew up living all across the world with plenty of spiritual influences, but without any particular religion. He is now a Christian, having been baptized in the early 1990s at Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago. But rumors about Obama’s religion persist. In the new NEWSWEEK Poll, 12 percent of voters incorrectly believe he’s Muslim; more than a quarter believe he was raised in a Muslim home.

His baptism presents its own problems. The senior pastor at Trinity at the time of Obama’s baptism was the Rev. Jeremiah Wright Jr., the preacher who was seen damning America on cable TV for weeks last spring—and will doubtless be seen again this fall. In the NEWSWEEK Poll, almost half of the respondents say Obama shares at least some of Wright’s views; nearly a third say Wright might prevent them from voting for the presumptive Democratic nominee.

The story of Obama’s religious journey is a uniquely American tale. It’s one of a seeker, an intellectually curious young man trying to cobble together a religious identity out of myriad influences. Always drawn to life’s Big Questions, Obama embarked on a spiritual quest in which he tried to reconcile his rational side with his yearning for transcendence. He found Christ—but that hasn’t stopped him from asking questions. “I’m on my own faith journey and I’m searching,” he says. “I leave open the possibility that I’m entirely wrong.”

The story of Obama’s faith begins with his mother, Ann. Raised in the Midwest by two lapsed Christians, she lived and traveled throughout the world appreciating all religions but confessing to none. One of Ann’s favorite spiritual texts was “Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth,” a set of PBS interviews with Bill Moyers that traces the common themes of religion and mythology, Obama’s half sister, Maya Soetoro-Ng, tells NEWSWEEK. When the family lived in Indonesia, Ann, on occasion, would take the children to Catholic mass; after returning to Hawaii, they would celebrate Easter and Christmas at United Church of Christ congregations. Ann later went back to Indonesia with Maya, and when Obama visited, they would take him to Borobudur, one of the largest Buddhist temples in the world. Later, while working in India, Ann lived for a time in a Buddhist monastery.

Visiting temples was not just tourism for Ann. “These kinds of experiences were a regular part of our childhood and our upbringing, and were important to [our mother] because they involved ritual,” says Maya. “She thought that ritual was very beautiful. The idea of human beings’ striving to be better, having the curiosity and questions about all these things, [was] perpetual and constant inside her.”

Did Ann believe in God? Obama calls his mother “an agnostic.” “I think she believed in a higher power,” he says. “She believed in the fundamental order and goodness of the universe. She would have been very comfortable with Einstein’s idea that God doesn’t play dice. But I think she was very suspicious of the notion that one particular organized religion offered one truth.”

Obama’s father, raised Muslim in Kenya, was, by the time he met Ann, “a confirmed atheist” who considered religion “mumbo jumbo,” writes Obama in “The Audacity of Hope.” (Barack Obama Sr. left the family when Obama was 2.) During his years in Indonesia, Obama went first to a Catholic school—and then to a public elementary school with a weekly class of religious education that reflected the dominant Muslim culture. He was raised, in part, by his stepfather, a man named Lolo, who “like many Indonesians … followed a brand of Islam that could make room for the remnants of more ancient animist and Hindu faiths,” Obama wrote in “Dreams From My Father.” “He explained that a man took on the powers of whatever he ate.” Lolo introduced young Obama to the taste of dog meat, snake meat and roasted grasshopper. In Indonesia, Obama has said, he saw women with and without head coverings and Muslims living comfortably next to Christians. He has said that his life among Muslims in Indonesia showed him that “Islam can be compatible with the modern world.”

Though Obama was a serious student in Hawaii—and, even then, a seeker—”Dreams” describes an adolescence there of predictable teenage drinking and smoking (and basketball). During his first two years of college at Occidental, he says, he was “not taking anything particularly seriously, or at least, on the surface, not taking anything particularly seriously.” After transferring to Columbia, though, the spiritual quest began in earnest.

People who knew him around that time describe a reserved, monkish man, uninterested in the extracurriculars of New York student life: bars, socializing, gossiping. William Araiza was in a political-science seminar with Obama their senior year, and what he remembers most is Obama’s detachment. “I don’t want to imply he was intentionally aloof, he just seemed like he wasn’t part of the college gang,” Araiza says. “He was the kind of guy who didn’t live in the dorms, didn’t hang out on campus.”

Obama’s first job out of college was at Business International, a research service in New York. “There was a lot of socializing,” says Beth Noymer Levine, one of Obama’s colleagues. “Here you had a hotbed of young singles—from the socializing there would be some storytelling—but [Obama] pretty much stayed out of that stuff … He was very together, very mature, and I was 23 and felt like a train wreck next to him.”

Obama says his spiritual quest was driven by two main impulses. He was looking for a community that he could call home—a sense of rootedness and belonging he missed from his biracial, peripatetic childhood. The visits to the black churches uptown helped fulfill that desire. “There’s a side very particular to the African-American church tradition that was powerful to me,” he says. The exuberant worship, the family atmosphere and the prophetic preaching at a church such as Abyssinian would have appealed to a young man who lived so in his head. And he became obsessed with the civil-rights movement. He’d become convinced, through his reading, of the transforming power of social activism, especially when paired with religion. This is not an uncommon revelation among the spiritually and progressively minded. (“There’s no more dramatic story in American life” than the story of the civil-rights movement, says North Carolina Rep. David Price, who knows Obama professionally and writes about politics and religion. “You could not continue to be kind and gentle in your personal life and also be denying other people’s humanity.”) When Gerald Kellman recruited Obama to go to Chicago as a community organizer, he remembers, the young man was “very much caught up in the world of ideas.” He was devouring Taylor Branch’s “Parting the Waters,” which is part history of the civil-rights movement, part biography of Martin Luther King Jr.

In Chicago, Obama found that organizers and activists there (and elsewhere) were employing a progressive theology to motivate faith groups to action. Using the writings of Paul Tillich and, especially, Reinhold Niebuhr—and also King, African-American and Roman Catholic liberation theologians, and Christian fathers like Saint Augustine—local religious leaders emphasized original sin and human imperfection. Christ’s gift of salvation was to the community of believers, not to individual people in isolation. It was therefore the responsibility of the faithful to help each other—through deeds—to respond to the call of perfection that will be fully realized only at the end of time. Adherents of this particular theology frequently refer to Matthew 25: “Whatever you neglected to do unto the least of these, you neglected to do unto me.” Everyone, in other words, is in this salvation thing together.

Obama’s organizing days helped clarify his sense of faith and social action as intertwined. “It’s hard for me to imagine being true to my faith—and not thinking beyond myself, and not thinking about what’s good for other people, and not acting in a moral and ethical way,” he says. When these ideas merged with his more emotional search for belonging, he was able to arrive at the foot of the cross. He “felt God’s spirit beckoning me,” he writes in “Audacity.” “I submitted myself to His will, and dedicated myself to discovering His truth.”

Was it a conversion in the sense that he heard Jesus speaking to him in a moment after which nothing was the same? No. “It wasn’t an epiphany,” he says. “A bolt of lightning didn’t strike me and suddenly I said, ‘Aha!’ It was a more gradual process that traced back to those times that I had spent in New York wandering the streets or reading books, where I decided that the meaning I found in my life, the values that were most important to me, the sense of wonder that I had, the sense of tragedy that I had—all these things were captured in the Christian story.” And how much of the decision was pragmatic, motivated by Obama’s desire, as he says in “Dreams,” to get closer to the people he was trying to help? “I thought being part of a community and affirming my faith in a public fashion was important,” Obama says.

The cross under which Obama went to Jesus was at the controversial Trinity United Church of Christ. It was a good fit. “That community of faith suited me,” Obama says. For one thing, Trinity insisted on social activism as a part of Christian life. It was also a family place. Members refer to the sections in the massive sanctuary as neighborhoods; churchgoers go to the same neighborhood each Sunday and they get to know the people who sit near them. They know when someone’s sick or got a promotion at work. Jeremiah Wright, whom Obama met in the context of organizing, became a friend; after he married, Obama says, the two men would sometimes get together “after church to have chicken with the family—and we would have talked stories about our families.” In his preaching, Wright often emphasized the importance of family, of staying married and taking good care of children. (Obama’s recent Father’s Day speech, in which he said that “responsibility does not end at conception,” was not cribbed from Wright—but the premise could have been.) At the point of his decision to accept Christ, Obama says, “what was intellectual and what was emotional joined, and the belief in the redemptive power of Jesus Christ, that he died for our sins, that through him we could achieve eternal life—but also that, through good works we could find order and meaning here on Earth and transcend our limits and our flaws and our foibles—I found that powerful.”

Maya says their mother would not have made the same choice—but that Ann understood and approved of Obama’s decision: “She didn’t feel the same need, because for her, she felt like we can still be good to one another and serve, but we don’t have to choose. She was, of course, always a wanderer, and I think he was more inclined to be rooted and make the choice to set down his commitments more firmly.”

After his stint as an organizer, Obama went to Harvard Law School. He didn’t officially join Trinity until several years later, when he returned to Chicago as a promising young lawyer intent on becoming a husband, a father and a professional success. Around the time Obama was baptized, he says he studied the Bible with gifted teachers who would “gently poke me about my faith.” As young marrieds, Barack and Michelle (who also didn’t go to church regularly as a child) went to church fairly often—two or three times a month. But after their first child, Malia, was born, they found making the effort more difficult. “I don’t know if you’ve had the experience of taking young, squirming children to church, but it’s not easy,” he says. “Trinity was always packed, and so you had to get there early. And if you went to the morning service, you were looking at—it just was difficult. So that would cut back on our involvement.”

After he began his run for the U.S. Senate, he says, the family sometimes didn’t go to Trinity for months at a time. The girls have not attended Sunday school. The family says grace at mealtime, and he talks to the children about God whenever they have questions. “I’m a big believer in a faith that is not imposed but taps into what’s already there, their curiosity or their spirit,” he says.

Amid the hubbub, Obama continued to try to work out for himself what it meant to be a person of faith. In 1999, while still in the Illinois State Senate, he shared an office suite with Ira Silverstein, an Orthodox Jew. Obama peppered Silverstein with questions about Orthodox restrictions on daily life: the kosher laws and the sanctions against certain kinds of behavior on the Sabbath. “On the Sabbath, if I ever needed anything, Barack would always offer,” remembers Silverstein. “Some of the doors are electric, so he would offer to open them … I didn’t expect that.”

Since severing ties with Wright and Trinity, Obama is a little spiritually rootless again. He lost a friend in Wright—and he lost a home, however tenuous those ties may have been toward the end, in Trinity. He has not found a new church, and he doesn’t plan to look for one until after the election. “There’s an aspect of the campaign process that would not make it a good time to figure out whether a particular church community worked for us,” he says. “Because of what happened at Trinity, we’d be under a spotlight.”

Nevertheless, his spiritual life on the campaign trail survives. He says he prays every day, typically for “forgiveness for my sins and flaws, which are many, the protection of my family, and that I’m carrying out God’s will, not in a grandiose way, but simply that there is an alignment between my actions and what he would want.” He sometimes reads his Bible in the evenings, a ritual that “takes me out of the immediacy of my day and gives me a point of reflection.” Thanks to the efforts of his religious outreach team, he has an army of clerics and friends praying for him and e-mailing him snippets of Scripture or Midrash to think about during the day.

The Rev. Kirbyjon Caldwell—who gave the invocations at both of George W. Bush’s inaugurals and presided over the wedding of the president’s daughter Jenna—is among those on Obama’s prayer team. When Caldwell talks about Obama, he can barely keep the emotion out of his voice. The thing that impresses him most, he says, is that when he asks Obama, “What can I pray for?” Obama always says, “Michelle and the girls.” “He never says, ‘Pray for me, pray for my campaign, pray that folks will quit bashing me.’ He always says, ‘Pray for Michelle and my girls’.”

But Obama’s faith is not without its critics. Some on the right say his particular brand of Christianity is a modern amalgam—unorthodox, undisciplined, even insincere. Last month Dr. James Dobson accused Obama of “deliberately distorting the traditional understanding of the Bible to fit his own world view, his own confused theology.” The campaign responded that Obama was reaching out to people of faith and standing up for families.

When Franklin Graham asked Obama recently how, as a Christian, he could reconcile New Testament claims that salvation was attainable only through Christ with a campaign that embraces pluralism and diversity, Obama tells NEWSWEEK he said: “It is a precept of my Christian faith that my redemption comes through Christ, but I am also a big believer in the Golden Rule, which I think is an essential pillar not only of my faith but of my values and my ideals and my experience here on Earth. I’ve said this before, and I know this raises questions in the minds of some evangelicals. I do not believe that my mother, who never formally embraced Christianity as far as I know … I do not believe she went to hell.” Graham, he said, was very gracious in reply. Should Obama beat John McCain, he has history on his side. Presidents such as Lincoln and Jefferson were unorthodox Christians; and, according to a Pew Forum survey, 70 percent of Americans agree with the statement that “many religions can lead to eternal life.” “My particular set of beliefs,” Obama says, “may not be perfectly consistent with the beliefs of other Christians.”

Last March, when video clips of Wright damning America blitzed the airwaves, Obama wrote a speech about race that he hoped would save his campaign. But it was, to some, also a speech about faith. Obama tried to explain his relationship with his pastor, to appeal to Americans’ sense of the best in themselves. He spoke of racial divides in America as “a part of ourselves we have yet to perfect,” and of his pastor as a flawed, human creature. “That speech,” says Paul Elie, the Catholic author of “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” “is steeped in Christianity. We have relationships, they’re all flawed, we’re all broken. You can’t renounce your history with a person at a stroke, we have to fare forward with other imperfect people and resist the claims to perfection coming from both sides.” After Wright’s performance a month later at the National Press Club, Elie says, Obama was right—and Christian—to repudiate him.

Did Obama see the race speech as a religion speech? Last week, aboard the campaign plane, he said: “Race is a central test of our belief that we’re our brother’s keeper, our sister’s keeper … There’s a sense that if we are to get beyond our racial divides, that it should be neat and pretty, whereas part of my argument was that it’s going to be hard and messy—and that’s where faith comes in.” As the general election wears on, Obama will have to summon all of his faith, in all of its complexity. Few things in life are harder, or messier, than the last months of a presidential campaign.