For Mitt Romney, it all started in a two-story, wood-framed house on a busy street in Pontiac, Mich. Painted beige, encircled by an asphalt lot that would hardly hold a dozen cars, the building manages to look both decrepit and picturesque, like a million other urban churches across the country. Today it houses the Unity Church of Practical Christianity, but until Romney was 10, it was the Mormon church he attended with his family—at least twice a day on Sunday, and one night a week for youth group.

Another presidential candidate, upon learning of a reporter’s visit there, might jump on the opportunity to reminisce about the faith of his childhood, to trot out fond stories about his pastor and the inspirational lessons learned at his knee. But not Romney. Seated in a plane between campaign stops near the olive groves of northern California, Romney hears of such a visit and the wattage seeps out of his smile.

“In Pontiac?” he asks.

Yes, the reporter answers.

“Oh, yeah. Wow. I don’t know where that is,” Romney says.

It’s still a church, the reporter says.

“Oh, it is. Oh, interesting.”

Full stop. Never has a man so polished looked so uncomfortable.

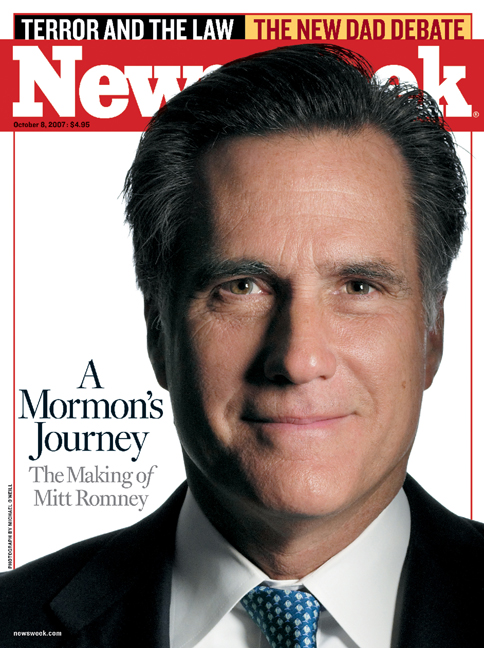

Nothing is more politically vexing or personally crucial for Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney than the story of his faith. Raised in a devout Mormon family by parents who were both principled and powerful, Romney has downplayed both his religion and his own family history. Instead, he has talked up his résumé as a private-sector “turnaround artist” who reversed the fortunes of troubled companies and the faltering Salt Lake City Olympics and now can come to his party’s—and country’s—rescue. Mindful of the sway of evangelical Christians over the GOP base, he has positioned himself as the candidate with conservative principles and strong faith, even adopting evangelical language in calling Jesus Christ his “personal savior” (vernacular not generally used by members of the Mormon Church). But when he’s pressed on the particulars of his own religious practice, his answers grow terse and he is quick to repeat that his values are rooted in “the Judeo-Christian tradition.”

It makes sense that a candidate seeking to be the first Mormon president would be hesitant to talk about his faith. More than 100 years after it outlawed polygamy, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints remains an object of mystery and ridicule for many in the country. In the new NEWSWEEK Poll, only 45 percent of registered Iowa Republicans say America is ready for a Mormon president—in spite of the fact that he’s the front runner in the state. Romney’s candidacy will be many voters’ first glimpse into the world of Mormonism, a world that embraces American ideals of hard work, frugality, self-reliance and optimism, as well as more off-putting aspects—such as a zeal for evangelism, an image that some see as overly wholesome and plastic, and secret temple rituals like baptisms for the dead. Romney’s biography is fully Mormon. When asked by NEWSWEEK if he has done baptisms for the dead—in which Mormons find the names of dead people of all faiths and baptize them, as an LDS spokesperson says, to “open the door” to the highest heaven—he looked slightly startled and answered, “I have in my life, but I haven’t recently.” The awareness of how odd this will sound to many Americans is what makes Romney hesitant to elaborate on the Mormon question.

This strategy has served him—to a point. Thanks to an efficient campaign organization, he is currently the front runner in New Hampshire and Iowa, where he leads his nearest competitor, Fred Thompson, by nine points in the NEWSWEEK POLL. While Romney still lags behind rivals Rudy Giuliani, Thompson and John McCain in national polls, many Republicans think his early-state lead and his personal wealth make him the most formidable candidate in the GOP field.

For all his strengths, however, Romney has been unable to shake his authenticity problem, the sense that he is a glossy and robotic candidate who will say anything to get elected and believes nothing in his heart. His trouble starts with his all-too-convenient conservative-conversion narrative: the pro-choice, pro-gay-rights governor of Massachusetts was miraculously transformed into a crusader for unborn life and the sanctity of marriage, just in time to run for the Republican nomination for president. But underlying the “flip-flopper” charge against Romney is a more disturbing perception, that the numbers-driven candidate is too cautious and committed to winning to explain what he believes in, including his church. “If you choose not to talk about the church and focus solely on Romney’s business and political abilities, you deny the public an opportunity to know him as intimately as the public demands of its front runners,” says Kirk Jowers, director of the Republican Commonwealth PAC and a Romney supporter. The fate of Romney’s candidacy may come down to one question: can he embrace his own biography to create a political and personal narrative that has heart—and soul?

The real Mitt Romney is a descendant of pioneer Mormons, a passionate lay leader, a lion of the modern LDS church. He is also the son of George Romney, the former governor of Michigan and president of American Motors, a straight-talking, hard-driven Mormon who stood up for what he believed in, even at great political cost. Born in Mexico in an LDS community devoted to perpetuating the practice of polygamy (George’s grandparents were polygamous; his parents were not), George finally settled in Salt Lake City. But his ambitions were always much bigger than the provincial society of Utah Mormons could satisfy. At 21, George returned home from his mission in England and Scotland, determined to court Lenore LaFount, a sophisticated girl who had recently moved east to Washington, D.C.

George wanted his parents’ blessing before following her there. His mother had died while he was abroad, so he and his father went to her grave together. “He wanted to be as close as he could on this earth to both his parents,” explains Mitt’s eldest sister, Lynn Keenan. There, at the grave site, George told “both of them that he would never dishonor the family name.” George had the conviction, unusual for his generation, that Mormons should live in the world, not out of it, and that a believing Latter-day Saint could thrive among nonbelievers.

Mitt (his given name is Willard) was born in 1947 in Detroit. He was the last of his parents’ four children. The Romneys made sure to keep the principles of the Mormon faith at the center of their children’s lives. Latter-day Saints believe that each person lived as a spirit with God before the creation of the world. The job of Mormon parents is to help their children adhere as closely as possible to God’s principles so the family can return to God in heaven and live out eternity together. Mormon rules against swearing, against the consumption of alcohol, coffee and tea, against extra- and premarital sex keep LDS members on the straight and narrow path back to the divine.

The George Romneys went to church each Sunday; it was not optional. Prayers were said over the evening meal every night, and family members took turns saying them. Tito Cortella was a 17-year-old exchange student from Turin, Italy, who lived with the Romneys when Mitt was about 12. “My English was not very good at that time,” says Cortella. “In spite of that, George Romney was asking everybody, one per night, to say the prayer. It was my turn, too. I had to learn it.”

The LDS Church is a lay organization: nearly every job within it is held by a member and not by professional clergy. From a young age, Mormon children are prepped to take on these leadership roles. Starting at the age of 5, they are expected to speak in church on simple spiritual and theological topics. At 8, they’re baptized. At 12, boys become “deacons”; they prepare and eventually serve the sacramental bread and water at worship services. Around that time, children can also do “proxy baptisms,” or baptisms for the dead. (These are mostly done on behalf of Mormons’ own ancestors, but they became controversial about a decade ago when it was discovered that they were also being done for dead Holocaust victims. The church ceased the practice, wherever possible.) When a boy turns 19, he often embarks on a two-year evangelizing mission; before he departs, he undergoes the sacred temple rituals for the first time. There are anointings and other secret rites, and he receives the undergarments that he wears almost all the time that mark him as a Mormon. All the observant males in the Romney family would have followed a trajectory that is something like this.

George drove his children hard, encouraging them to be industrious and to “make good choices,” a phrase common in Mormon circles. Phillip Maxwell, who went to high school with Mitt and is a Birmingham, Mich., lawyer, says it was difficult to make plans with the Romney boys on weekends because, in addition to the demands of their church, their father gave them so much yardwork to do. “When old George looked you in the eye, you did what he told you,” says Maxwell.

George also enforced his belief that his Mormon children had to be integrated into the world and respect people of different backgrounds. Cortella remembers his Roman Catholic mother’s being apprehensive about sending her son into the bosom of a Mormon family—until the first Sunday he spent at the Romneys’ house. “It was about 11 o’clock in the morning,” Cortella says. “Mr. Romney said, ‘You come with me.’ He took me to the Catholic church not far from the house. He said, ‘From now on, every Sunday you will come to this church,’ and he was getting mad if I was not going.” In an even starker example of the senior Romney’s live-and-let-live policy, Cortella says the Romneys allowed him to smoke cigarettes in his room.

If Mitt chafed under the demands of his idiosyncratic father and his faith, he didn’t show it. At Cranbrook, the elite private high school he attended in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., classmates say he was the only Mormon they knew, but that he wore his religion, and his social status, lightly—seemingly perfectly at ease with the contradictions in his life. He was known as an amiable, unpretentious boy who enjoyed a joke—a quality inherited, perhaps, from his mother. “My mom had a great sense of humor,” says Romney, “and she had an infectious laugh, which, I’ve determined, is a great attribute. It makes you instantly popular.” The teenage Romney was a prankster. His classmate Maxwell remembers one evening when the boys borrowed Maxwell’s father’s Chevy coupe, which looked like an old police car. Mitt cadged his father’s State Police badge and Maxwell put on his uncle’s Air Force uniform. Posing as cops, the boys pulled over two buddies on a double date, “arrested” them and drove away, leaving the astonished girls behind.

At 18, Mitt fell in love. Ann Davies was three years his junior, Episcopalian and by all accounts a knockout. She soon converted to Mormonism; George performed the ceremony. Mitt and Ann agreed that they would marry. But first, Romney had to go on his mission. After an undistinguished year at Stanford University, he flew to France, where he set about knocking on doors—and pining for Ann. He persuaded his father to send him extra money so he could call her, says Michael Bush, a professor of French at Brigham Young University who served as a missionary with Romney. This was unusual: Mormon missionaries rarely called home, both because it wasn’t encouraged and because most of them couldn’t afford to. (Now rules dictate that missionaries can call home two or three times a year.) But Mitt “was totally in love,” says Donald Miller, a dentist in Calgary who was one of Romney’s missionary “companions,” which means that they almost never left each other’s side. “I would have to go down to the post office every other week while he phoned home and talked to his girlfriend,” says Miller.

The life of a Mormon missionary is relentless, but to be in France during the Vietnam War was especially grueling. Anti-American sentiment was fierce, and the people Romney approached—Catholic-born, secular-minded—were mostly not interested in his message. Miller says he knocked on hundreds of doors every day for 30 months and was responsible for just two convert baptisms.

But during the mission, the mature Romney came into focus. He excelled at the French language and at memorizing the lessons he was to give listeners. The local mission office kept records to quantify missionaries’ success, and Romney was a top performer. He was eventually promoted to assistant to the mission president, the highest mission post. In the summer of 1968, he set to work motivating his fellow missionaries. “Nothing is impossible for men who are marching in unison,” he wrote in a pamphlet. “They can destroy bridges or they can build new ones.” LDS members say nothing molds a man as much as his mission, where, deprived of any diversion, he must concentrate fully on his future and his God. Mitt became a serious person in France.

In his last mission year, 1968, Romney’s father was the front runner in the Republican presidential primary—and then, humiliated, was forced to withdraw. Mitt has said the experience barely affected him, but close observers have a different take. Romney Senior was exploring a presidential run when, in September 1967, he said the words that made him notorious. When he visited Vietnam in 1965, he said he thought the United States was engaged in a “morally right and necessary” war. But after investigating, Romney told a Detroit radio station he believed he had been “brainwashed” by the military and the diplomatic corps. “As a result,” he said, “I have changed my mind.” In retrospect, it sounds like a dramatically principled statement. At the time, the elder Romney was excoriated for “flip-flopping,” and in February 1968 he dropped out.

Gerald Anderson, another missionary contemporary who is now an agrologist in Alberta, Canada, recalls visiting with Mitt in Paris around that time. One of the fellows asked Mitt, “What do you hear from your father?” and, says Anderson, Mitt answered, “I hope nothing.” What Romney meant, Anderson believes, is that his father said more than he should have. Perhaps it was then that Romney learned the political value of keeping mute. “That’s one reason Mitt is very measured in what he says—he doesn’t want anyone to seize upon anything he says to scuttle his campaign like they did his father’s,” says Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, who is a Latter-day Saint and says he knew the father well.

After the mission, Romney transferred to Brigham Young, where Ann was enrolled. Within three months, they were married. Outside Provo, the world was in chaos: Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated; college students rallied against the war. But in Provo (a.k.a. Happy Valley) all was calm, and Romney flourished. “The idea of going to a place where there was a gathering of the Saints had an attractiveness to Mitt,” says fellow missionary Dane McBride, a Roanoke, Va., physician who knew him at BYU. During his time there, Romney took on a backbreaking workload: he was a new father, a leader in the local church and, by the time he graduated in 1971, valedictorian of his class. One shadow fell over Romney’s otherwise blissful time in Provo: in 1970, his mother ran for Senate in Michigan and lost.

His parents’ campaign disappointments left Romney wounded, but it was not yet time for him to avenge their losses. At the dinner table in Bloomfield Hills, Mich., George Romney had taught his children a rule about running for office: wait until you’ve made enough money to be beholden only to yourself. “His rules were, you should be financially independent so that you don’t have to win an election to pay your mortgage,” Mitt says. After graduating with degrees in business and law from Harvard in 1974, Romney went to work as a management consultant at Boston Consulting Group, where he quickly earned a reputation as a “comer.” The son of a celebrated politician, the most handsome man in the room, the ardent missionary, Romney had been rehearsing for the role of corporate go-getter all his life. “Mitt clearly thrived in that environment,” says Todd Hixon, a Harvard classmate who worked with Romney at BCG. “He was one of those guys who got everything right.”

Getting it right meant getting rich. In the mid-’80s, Romney launched Bain Capital, a private-equity spinoff of the esteemed Boston consulting firm Bain & Co. His success sprang in part from the values taught him by his father and reinforced by his faith. When evaluating a company for investment, Romney and his staff would tear apart company financials, grill managers and contact suppliers and competitors to produce an assessment of the business’s strengths and weaknesses. Romney’s genius as an investor, colleagues say, came from having the discipline to say no to most deals, even some that promised big windfalls in the short term. Bain’s ethic was essentially Mormon: make good choices because you’ll have to live with their consequences.

In his private life, Romney stuck even closer to the principles of his youth. In 1971, he and Ann bought a house in Belmont, a quiet bedroom community that would be the Romneys’ home base for the next 30-plus years. Here, Romney could raise his five sons much as he had been raised. The boys were children of privilege, but were nonetheless expected to follow a strict routine of Saturday-morning chores, youth group on weeknights and church on Sunday. The Romneys wanted their boys to live a life of order, discipline and faith, but most important, they had to choose it for themselves. “There was never any ‘You have to go to church or else’,” Romney’s son Tagg told NEWSWEEK EARLIER this year. “They led by example.”

Church was at their father’s core. In the mid-’80s, just as he was starting his business, Romney helped form a new ward (equivalent to a parish) in Belmont. He would serve as its bishop from 1985 until, in 1986, he assumed the presidency of the Boston stake of the LDS Church (equivalent to a diocese). These were demanding jobs, particularly for the father of growing children with an all-consuming career. As bishop, Romney was responsible for the administration of religious services. His responsibilities to his flock included counseling couples whose marriages were in trouble, instructing youth and distributing charity to church members who had come on hard times.

Romney the churchgoer was much like Romney the capitalist. Serving as Boston stake president in the early ’90s, he led an effort to build a new chapel on a patch of undeveloped land in one of the city’s industrial suburbs. Others in the stake were skeptical—the lot was a desolate expanse of concrete and weeds. Would there be enough Mormons in the area to go to church there? But Romney saw a good deal for a rapidly growing faith and insisted. “He was right,” says Kent Bowen, a member of the Belmont ward. “There are now many, many people who go to chapel over there.”

But Romney was careful to keep his professional and private lives separate. Many of his colleagues at Bain knew little about the details of his religious observance. Like his father, he kept liquor in his home for non-Mormon guests and was careful not to impose the strictures of his faith on the outside world. When Bain invested in a film studio with a large catalog of R-rated films, Romney struggled internally. R-rated movies are frowned upon in the Mormon faith, but the deal looked good for Bain. Romney’s solution: make the deal happen, but skip his usual practice of putting some of his own money into it as well. “I didn’t want to profit from a studio that made R-rated movies,” he told The Boston Globe earlier this year.

But Romney’s carefully constructed barrier between secular and spiritual came down when he entered politics. By the early ’90s, he was a millionaire a hundred times over; long since self-sufficient, he was ready to run for office. His shot, which came in 1994, was not ideal: running as a Republican against Ted Kennedy, who was seeking a fifth full term representing Massachusetts in the U.S. Senate. But it was the shot he had. Romney launched himself as a fresh-faced, moderate alternative to the old liberal lion. George and Lenore Romney temporarily decamped to Belmont to advise their novice son.

From the start, Romney made clear that questions about his faith were out of bounds, and from the start, his faith was all anyone wanted to talk about. The Boston papers were filled with tales of his secret Mormon life. As bishop, he’d counseled a Mormon woman not to have an abortion. As stake president, he’d called homosexuality “perverse.” (Romney denied making this comment.) The tales fed the notion that there was something sinister inside Romney, that beneath the mild-mannered moderate lurked a secret extremist. When Kennedy suggested that Romney should have to answer for the LDS history on race (until 1978, African-Americans couldn’t hold the priesthood), Romney called an angry news conference to condemn Kennedy for forgetting his own brother’s admonition that a candidate’s religious beliefs had no place in the public sphere. George—who was shredded by the press during his presidential run, but not on account of his religion—stood behind Mitt as he made his statement. Growing impatient, George seized the microphone: “I think it is absolutely wrong to keep hammering on the religious issues.” The high road turned out to be a problematic course.

In the three decades since the elder Romney had last run for office, religious issues had moved to the center of American politics. In the White House, Bill Clinton talked openly about his relationship with Jesus Christ. On the campaign trail that fall, young, Republican candidates were promising a conservative crusade that would restore moral values and make America a more godly place. But Romney, as godly a candidate as any, could not join their number. In November, he lost the race to Kennedy, primarily due to a lack of experience and the resilience of Camelot in the Bay State. The race left his advisers with a question: would Romney’s faith prevent him from achieving the political life he’d always planned to have?

The answer came in a detour to a place where being Mormon wouldn’t be a problem. In 1999, Romney accepted an invitation to move to Utah to take over planning for the 2002 Olympic Games in Salt Lake City. The Games were a mess after revelations that organizers had wooed members of the International Olympic Committee with high-priced bribes. The Games were supposed to be Utah’s moment in the spotlight and Mormonism’s chance to emerge from the fringes. Now they seemed only an opportunity to be embarrassed on an international stage. “I walked into the Olympic building,” Romney recalls, “and people looked like somebody had just died.”

Romney had to be a savior in a very public setting, and he thrilled to the chance. Recruiting new chief financial and chief operating officers, he immediately imposed cuts. Using the skills he’d learned at Bain to take companies apart and put them back together, Romney immersed himself in the tiniest details of the Games’ management. Even fun was mandated: he decreed that every meeting would start with a joke. Three years of obsessing over details did the trick; the Games went off without incident and turned a $50 million profit. Romney was heralded as a hero in Utah, and many urged him to run for governor of the state.

Massachusetts Republicans, however, wanted another shot at Romney, a chance to see more in him than his faith. With the Olympics barely over, he returned East in 2002 and announced his candidacy for governor. He would not be Mitt the Mormon this time, but Mitt the turnaround specialist who could work his Salt Lake City magic to save Massachusetts from fiscal ruin. The Boston press bought it; it had already written the Mormon story. Romney solidly beat Democrat Shannon O’Brien and took control of the governor’s office in January 2003.

Romney finally had his chance to fulfill his father’s wish for him, to govern with principle, and his own wish for himself, to be his state’s white knight. The problem was that the powers on Beacon Hill, where a Democratic legislature was entrenched, weren’t convinced Massachusetts needed saving. By his own admission, Romney was best at throwing his energy at a single, looming threat. When asked about his greatest flaws, he says, “I’m not the most organized of managers. I tend to immediately concentrate on what I think is the most difficult problem.” It was a strategy that served him well in business, where his subordinates could sweat the small stuff. But a governor had to be comfortable making tiny compromises to gain the opposition’s trust. Romney recoiled from backroom dealmaking, and many legislators wrote him off as a prissy novice.

Apart from an innovative plan to provide universal health care, Romney’s single term as governor was in many senses a disappointment. Unable to work with the Democrats, he instead chose the TV camera as a governing partner. When the state Supreme Court made Massachusetts the first state to allow same-sex couples to marry, Romney rose in passionate opposition and became the most prominent, and telegenic, gay-marriage critic in the country. Around the same time, he revised his views on abortion, saying he was now not only personally opposed to abortion, but favored overturning Roe v. Wade. When he announced his candidacy for the presidency, shortly after leaving the governor’s office in January 2007, he had reinvented himself as a social conservative ready to take on a moderate GOP field. Conversions of convenience were frowned upon in young Mitt’s upbringing, but the adult Romney seemed untroubled.

The Mormon question loomed larger than any other over Romney’s young campaign. As governor, he had demonstrated he was not interested in imposing the doctrines of his faith on the people of Massachusetts. (For example, he signed a law abolishing the state’s centuries-old “blue laws,” prohibiting the sale of alcohol on Sundays. “I could serve alcohol in the White House,” he says.) But evangelical Republican primary voters, many of whom view Mormonism as a heretical cult, were a major concern. In the months leading up to his announcement, Romney met privately with conservative Christian leaders to highlight his positions on social issues. At a meeting with 15 top evangelical leaders in Belmont in October 2006, he stressed commonalities between Mormons and other Christians. Most important was a single phrase: “I accept Jesus Christ as my personal Lord and savior”—a phrase that backfired in certain quarters. Although it is a true representation of Romney’s beliefs, some conservative evangelicals were offended that he appeared to be co-opting their language for political gain.

Romney and his campaign wanted to deal with the Mormon question quickly and move on. The Massachusetts experience taught that Mitt the Mormon lost elections and Mitt the turnaround artist won them. In the first weeks of the campaign, Romney sat for lengthy interviews on his faith with The New York Times and USA Today; if the campaign could make the Mormon factor a tired story line, reporters would have no choice but to write about something else.

Sure enough, another story line quickly fixed itself to Romney: Mitt the flip-flopper. From the outside, Romney’s ideological conversions looked opportunistic. He had been a social moderate to win election in liberal Massachusetts—and reinvented himself as a social conservative to be viable in the primary race. With Romney reluctant to keep talking about the full story of his faith and family, he seemed to be failing to live up to the high principles of either. Candidate Mitt seemed a far cry from his father, who had condemned his party’s presidential nominee in 1964 for making insensitive comments on race, and who had eventually sacrificed his own presidential ambitions by making the cardinal error in politics of saying what he thought about the war in Vietnam. “George was a man of strong principle who got into trouble when he stated his views directly and honestly,” says Jonathan Moore, who advised the elder Romney on foreign policy in the 1968 campaign. “Mitt gets into trouble when his shifting of position to fit political circumstance suggests a lack of principle.”

So what kind of president would Mitt Romney be? It often seems that Romney himself doesn’t know. More disturbing, he is also unwilling to truly look to his own history for the answer. Asked by NEWSWEEK how he is most like his father, Romney saw only an opportunity to recite a familiar talking point about his own style as a manager, noting that George “did not just ask for opinions but for thoughtful analysis and data.” Everything his family has lived through—religious persecution, the traversing of a continent, a noble tradition of service and the depths of political disappointment—it all pales in comparison with data. This is the man who in the great wisdom of political insiders is seen as congenitally presidential?

In fairness, it is true that Romney has the stuff of great presidents somewhere inside him. The making of Mitt Romney included the development of skills any leader would find invaluable—a strong work ethic, an insistence on sacrifice and a reverence for those who put the principles of humanity over the conveniences of the moment. But, to date, these traits have been hard to find in the public Mitt Romney. All that is really recognizable in him is a capacity for organization and packaging that are characteristic of his faith. Unfortunately, the politician Romney has been chiefly interested in organizing and packaging himself into is a man who seems to have no history, and, as a result, no heart. Latter-day Saints talk a lot about moving forward and making good choices. Going forward, Romney the candidate will have to search his soul and make some good choices about who he really is and what kind of president he wants to be.