He had places he belonged and people looking out for him. How did he end up dying, alone, at the hands of a stranger?

For a brief period in his life, starting when he was 12, Jordan Neely had a home. It was on the first floor of a small yellow two-family house in Bayonne, New Jersey, where he lived with his mother, Christie Neely, and her boyfriend, Shawn Southerland. Jordan was Christie’s only child, and the two were “like peas in a pod,” his great-aunt Mildred Mahazu said, “wild about each other, like children playing.” Christie would wake him each morning by calling his name, and she’d fuss over him and insist on washing him before hustling him out the door to meet the bus at 7 a.m. Christie had a light, teasing manner with the people she loved, but with Jordan, she could be strict. Her rules included that Jordan couldn’t skip school and that he should never cook while alone in the house. Christie worked nights at a telemarketing firm near Herald Square in Manhattan, and when she got home, usually around 9:30 or 10 p.m., she’d poke her head into Jordan’s room. Jordan would say “good night,” then stay up playing video games until midnight.

Before moving to Bayonne, Jordan and Christie had stayed in several shelters in New York; Jordan’s 10th birthday passed at the Regent Family Residence, a transitional shelter on the Upper West Side where people go to right themselves as they find work or try to obtain affordable housing. Christie had family and places to live, but she was proud and independent and wanted a place of her own where she and her son could feel settled. While in the shelter, Christie had enrolled in classes to become a paralegal, and that’s how she met Southerland, who sat one seat over. When Christie rented the house in New Jersey, Southerland moved in.

Things weren’t perfect. Southerland had put a padlock on the main bedroom’s door so Jordan couldn’t enter. And he was jealous, the kind of boyfriend who would call Christie ten times an hour if she was doing something out of the house with a friend or her own mother. Christie and Southerland argued a lot, and sometimes one of them would leave and spend the night out. Even then, Christie was always in touch with her son by phone, telling him where she was and what time she’d be home. In that yellow house, Jordan had all that he needed, including his own bedroom with a PlayStation, DVD player, and television set; a bike in the backyard; and a freezer full of food.

Then, one morning early in April 2007, when Jordan was 14, Christie didn’t wake him for school. Jordan got dressed and headed to his mother’s bedroom to say good-bye, and he found Southerland blocking the closed door. Southerland was big and menacing, so Jordan left it alone, and upon returning from school, he inquired again about his mother’s whereabouts. But Southerland was not forthcoming, and later that night he departed the house in a borrowed car with a story about an aunt on her deathbed and never came back. For several days, Jordan kept to his routine. (“I told my school-bus driver and I told my principal, ‘I haven’t seen my mom in the house,’” Jordan said when he took the stand in 2012 during Southerland’s trial.) Then he called her work. When a colleague said they hadn’t seen her either, “my heart beat,” he recalled, and he began to be afraid. He was hungry. “I don’t know what to do. It’s cold. The mail keeps coming in. The heat went off,” he said. Still, he didn’t try to cook for himself. He kept expecting his mother to walk in the door and didn’t want to get in trouble.

After a few more days, Jordan got on his bike and cycled to his aunt Carol’s house in Jersey City. Carol Kasse was not a blood relative but Christie’s best friend, and Jordan sometimes stayed with her in her doorman building when Christie was working overnight. Single and with no children of her own, Kasse called Jordan “my baby.” She would arrange a mattress on the floor and get him chicken and fried rice from a Chinese restaurant. But upon arriving in Jersey City, Jordan found that Kasse was out. Upset and not knowing what to do, he ditched his bike and hopped the turnstile at Journal Square, where he got on a path train to 33rd Street, then took the D to the A to 175th Street in Washington Heights to his grandmother’s house.

The following day, a Monday, Jordan, together with his maternal grandparents, an uncle, and his great-aunt Mildred, was back at the house in Bayonne. A police officer was there too, to help them file a missing-person report. When Jordan’s uncle Christopher reached Southerland by phone, Southerland said Christie had gone on vacation. He bought her a suitcase, he said. But Jordan knew this couldn’t be right because his mother would never leave town without letting him know. All the while, the TV was on in the living room, and amid the confusion, a news broadcast came on: A woman’s body had been found in a black expandable duffel bag by the side of the Henry Hudson Parkway in the Bronx. Wrapped in black plastic, clad in jeans and a T-shirt, the corpse was decomposed, and the police were trying to make an ID. There, on the television screen, flashed Christie’s belongings: a black-and-silver belt and a turquoise ring. Jordan began bellowing and beating the walls.

By the time Jordan testified at Southerland’s trial, he was 19 years old. He had built a new life as a Michael Jackson tribute artist in New York City. He owned a Michael wig, which he kept neatly styled; military-type jackets in red and black with gilded trim and epaulets; a white glove. At the trial, Southerland was representing himself pro se, which meant that during his cross-examination, Jordan had to answer questions posed by the same man who had intimidated him and lied to him as a child and who would later be convicted of murdering his mother. Under oath and appearing composed, Jordan relived the morning his mother didn’t wake him for school. Southerland referred to himself as “the defendant” or “Mr. Southerland,” but Jordan refused to play along, addressing his questioner as “you.” It was agonizing to watch, recalls Kristen Brewer, then a young assistant prosecutor who observed the trial. Jordan had bounced around in the five years since his mother’s murder, and Brewer was struck by the earnest truthfulness with which he took the stand. She says she remembers thinking, “If this young man can even manage stability, we’ll have asked a lot of him.”

Christie Neely met Andre Zachery at Sweetwater’s on the Upper West Side, where Zachery was dining with his friend Pharoah Davis. The men composed half of an R&B vocal quartet called Asanté. Christie was gregarious with a wide smile, and Davis did the talking, while Zachery — tall, slim, with bladelike cheekbones and perfect pitch — held back. Jordan, the child of Christie and Zachery, was born on December 18, 1992. Zachery asked Davis to be the infant’s godfathe

Zachery’s own mother had died when he was 13, and he had survived as a child by singing with bands in Harlem and the Bronx and living with some older band members. Years later, whenever the members of Asanté rode the subway, they would try out tunes in the tunnels and on the platforms and watch people’s reactions. “There’s nothing like the acoustics in the subway,” Davis says. “You can hear your harmonies bounce back off the walls.” The group often rehearsed in the large Morningside Heights apartment belonging to Davis’s father; women would stop by to hang out, and Jordan, at about 5 years old, would squeeze in beside them. Davis says he remembers thinking, “Jordan is smooth without saying a word.” When his son was around, Zachery liked to put Michael Jackson tapes in the VHS player. Zachery loved Michael, not just for his perfectionism and his obsessive work ethic but also for the way his music evoked the R&B greats that came before him — David Ruffin, Jackie Wilson, James Brown — and he wanted to familiarize his son with “the best,” Davis says.

Christie and Zachery’s relationship was volatile. She was straightforward and ambitious; Zachery, whose main source of income came from working as a super in buildings uptown and in the Bronx, was more passive — “meek, very meek,” Davis recalls. Davis remembers having to go to his apartment and rouse him out of bed to come to rehearsal. According to Mahazu, Jordan and Christie lived with her in her Harlem apartment when he was an infant, then Christie and Zachery tried to make a go of it and rented a place together. But by 1995, they were on the outs again. And when Asanté broke through with a Billboard “Hot R&B” single titled “Look What You’ve Done,” a smooth, sexy tune that stayed on the charts for 20 weeks, Mahazu watched with disapproval as Zachery wasted his money and slept around.

When Christie was murdered, it was not immediately clear where Jordan would stay. While Jordan was living in New Jersey, Zachery was not involved in his life. Kasse wanted to take charge of him, but Clara Neely, Christie’s mother, was next of kin. Immediately after Christie’s death, Jordan stayed for a while with Kasse. “I always promised his mom, ‘I’m going to look after your son, no matter what,’ ” she says. For his privacy, she erected a partition in her living room, where he slept.

Jordan lost hold of himself after his mother died. He would stutter, stare off into space; when Mahazu asked what was the matter, he would say, “I miss my mama.” He had been a gentle, charismatic child, but now he stopped heeding the adults in his life and started skipping school. When Kasse tried to reprimand or discipline him, he’d leave her house, hop on the path, and go to his grandmother’s apartment in Washington Heights. When Clara did the same, he’d travel back to New Jersey.

By the time he was 16, Jordan was living with his grandparents and had enrolled at Washington Irving High School near Union Square, where he was already trying out Michael Jackson routines on classmates. Meanwhile, Kasse was in touch with his family, getting updates, but without legal authority to intervene in his care, she grew frustrated. Then she met the man who would become her husband, and he wanted to move to Florida. Kasse likes a peaceful life, she told me, and her dealings with the Neelys had become contentious. She called Jordan. She said she was moving to Florida and was happy to buy him a plane ticket. Christie had always promised Jordan they would move to South Beach before he finished high school, and Kasse told him he could live with her, get some therapy, and go to school down there. Jordan said he would go, but then he didn’t. “He told me his family said he couldn’t,” she says, and she never knew whether they had stopped him or he simply didn’t want to. “You can’t make somebody be somewhere.”

Jordan Neely stood in the crowd at the corner of 40th and Broadway, watching the B-boys dance. He was about 16 years old and dressed in blue. Dwayne Blizzard had been leading this rotating crew since the 1980s — they called themselves the Float Committee — bringing the break-dancing moves he learned as a kid in the Bronx to midtown, where the tourists and commuters were. For Blizzard, break-dancing was better than any day job. It gave him joy, fans, exercise, and an income. The Float Committee were the dancers you saw in the Herald Square subway station or on the wide sidewalks of Times Square, skipping and hollering in call-and-response, spinning and crab-walking, sometimes with a sharp drummer beating on an upside-down tub. Over the years, Blizzard had learned to start off his sets with Michael, who was more pleasing to the masses than “this hard-core B-boy shit.” In high tourist season, Blizzard could earn $150 to $200 per day.

Jordan approached Blizzard after the show. He said, “I like Michael Jackson. I dance.” Blizzard asked to see a few moves. “He was all right,” Blizzard remembers. But he told Jordan, “Michael don’t wear blue. He wears black.” As for his moves, “I said, ‘You got to brush up a little bit.’”

Blizzard saw in Jordan an opportunity. The Float Committee was already dancing to Michael, and Jordan, a handsome kid — nice, respectful — wanted to be Michael. So Blizzard got Jordan’s number and invited him to his apartment in Harlem and set him up in front of the television with Michael’s live concert footage: “He was studying it. I said, ‘Bro. See how he did that? Do it with ease; don’t even worry about it.’” From then on, they practiced every day, though Blizzard had a rule: They couldn’t start until the school day ended. Jordan was still a teenager, after all, while most of the Float dancers were in their 30s. After school, Blizzard and Jordan would practice Michael’s moves in Blizzard’s apartment or in a nearby park on a smooth piece of folded-up cardboard. Blizzard bought Jordan his first Michael Jackson outfit at a costume shop on 14th Street.

Jordan soon became the headliner in Blizzard’s show. The act would start with a familiar tune — “Billie Jean,” “Thriller,” “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough” — the B-boys would break, then Jordan would step out from behind the other dancers, spinning, sliding, and moonwalking, before drawing someone out of the crowd to dance circles around them. In a skullcap, sunglasses, and an oversize jersey, Blizzard was the master of ceremonies, pumping the audience up and passing the hat. Jordan “was a little shy at times, but once he got into his Michael, he’d let it go,” Blizzard remembers. “The dancing brought him out of his shell, made him feel more love for himself, and made him not worry so much about what was happening in his life.” After an evening performing on the streets, Blizzard would accompany Jordan to his grandmother Clara’s apartment in Washington Heights.

In the years between 2009 and 2012, Jordan became a recognizable person on the streets of New York. Passersby would photograph or record him in the subway: In videos, he’d spin and smile as the train hurtled from station to station with everyone in the crowded car smiling in admiration, nodding or clapping along. His celebrity was propelled in part by the superstar’s death on June 25, 2009. There were so many tribute concerts and performances that year, recalls Moses Harper, another Michael Jackson tribute artist. One day that summer, she had finished a dance rehearsal, changed back into her street clothes, and was walking through Times Square toward the subway. There, she saw Jordan in the middle of a big crowd, not with Blizzard’s crew but with a couple of teenagers like himself, wearing sweatpants and sneakers and dancing to some of Michael’s older songs: “Rock With You,” “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground).” Harper lingered, watching. They were just kids messing around, she says, and she felt their joy. She will never know why Jordan singled her out, beckoning her to join him, not realizing that she — 14 years his senior — was already expert in Michael’s moves or that she happened to have a white glove in her back pocket. She put on her glove, took the fedora off Jordan’s head and placed it on her own, and they danced together to “Billie Jean.” Afterward, they hugged and exchanged phone numbers.

Jackson superfans “tend to be misfits, sometimes,” Harper says. His embodiment of magic, fantasy, and innocence held special meaning for people who had grown up in some way orphaned. That summer, Harper and Jordan grew close, and one night, as she was walking him back to his aunt’s apartment in the rain, he told her about his mother’s murder. He was crying. “We related because we traded stories,” Harper says. “My mother was a heroin addict and an alcoholic. She drank two quarts of liquor a day before I was even born, and I was born a drug addict.” Harper worked in jails and schools mentoring at-risk kids and had experience with teenagers like Jordan.

Michael Jackson impersonators got flak because of his horrific history of abuse. Harper describes regularly being called “child molester” by passersby. She dealt with this occupational hazard neutrally. “I’m not Michael Jackson,” she would say. “I’m just wearing this jacket.” But Jordan took the hecklers to heart. The first time it happened, he called Harper, aggrieved. “He was saying, ‘Why? Why?’ ” she recalls. He had just been out there minding his own business, not robbing people or selling drugs, he complained, just enjoying himself. Harper said, “Sweetheart, I don’t know. Let them talk.”

At Halloween time for several years in a row, Blizzard would take Jordan to New Jersey and they’d enter dance and costume contests at local clubs. Blizzard and his dancers would come onstage dressed all in black, then Jordan would enter as Michael. “We would win them all. A thousand here, $2,000, $5,000 here,” Blizzard says. Jordan never wanted to take off his costume. One night, the whole group went out to a restaurant in City Island with Jordan still dressed as Michael; the management offered them $500 to perform on the spot, and they did. Their partnership was so profitable that Blizzard was making plans to take their act to Asia. Blizzard had spent a couple of years dancing in Taiwan and Japan back in the 1980s. “They’re more sensitive to icons over there,” he says. “If he had gone to Japan, he would have never come back.”

As he got older, Jordan started disappearing. No one could find him for days or even weeks at a time. Blizzard calls this “going ninja.” His grandmother was growing frustrated with him. They fought, and sometimes she would lock him out. On those nights, he had to sleep in the hall and a neighbor would bring him a plate of food. “It just got so nobody could rule him. It’s not like he was thrown away,” Mahazu says. He seemed to prefer being outside, in the wild, on his own. “He couldn’t follow the rules and regulations. He didn’t like being told what to do,” she adds. Sometimes he would stay with Clara, sometimes with Mildred or his aunt Carolyn or uncle Christopher, but he had ceased being a cute kid. Clara was chronically ill, her marriage was strained, and she had five living children. (Jordan’s aunts and uncles declined to comment; Clara died last summer.) As an adult, “you don’t want to wear out your welcome,” Pharoah Davis explains. “When you’re older, when you’re not ‘Little Jordan,’ it’s different.”

At 18, Neely went to live in the Bronx with his father, Andre Zachery. “Dre was scratching and surviving,” Davis says, and working for the city as a park attendant. Blizzard recalls Zachery asking his son to share the proceeds from his performances. When Neely refused, they fought, and Zachery would take away his house keys. (Zachery denies that this ever occurred.) Neely seemed depressed and introverted, Davis says, but he was proud, like his mother. “He wasn’t the type of person to constantly leech off somebody,” Davis says. The first recorded instance of Neely registering at a shelter as an adult was in April 2011. It was the Bellevue Men’s Shelter, a massive temporary dorm that formerly incarcerated men say is more violent than prison. He was 19 years old.

Not long after, Neely stopped dancing with the Float Committee. Blizzard would call the group to meet at an hour and a place, and Neely would show up late or not at all. He had started performing solo in subway cars and, as time went on, began to hang out alone with a boom box in Times Square, moonwalking on a short stretch of pavement, taking pictures with tourists at $5 or $10 a shot. Blizzard speculates that the money was easier and he could keep to his own schedule, but Blizzard had been worried. “His father should have taken better care of him,” he says. Neely needed “more love, love, love.” Blizzard believed the pleasure of dancing with others and the rigor of being part of a crew were good for Neely. Once in a while, Neely would stop by where the group was dancing and Blizzard would encourage him to join. But Neely, embarrassed, would demur. “Yeah, man, I’m getting it together,” he’d say. He had begun to look spaced out and disheveled. Blizzard would give him $50 or so. He’d say, “Go get yourself cleaned up.”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah, I’ll be back,” Neely would say.

“And then he didn’t come back,” says Blizzard, though Neely would sometimes stop by Blizzard’s to sleep and shower and watch a little TV.

The people who work with those on the streets — outreach workers, social workers, nurses, police, psychologists, psychiatrists, physicians — say they frequently notice a pattern of traits. The majority have lived through damaging experiences that may impede their ability to maintain relationships and, sometimes, to care for themselves. Many additionally have a mental illness — schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disease, major depression — which may be triggered or worsened by the underlying trauma and further exacerbated by the experience of being homeless itself: the hunger, the exposure, the loss and theft of belongings and documents, the police, the barriers to housing and help, the cumulative effects of sleeplessness. Many also use substances to quiet their brains or numb their distress. The interplay of these forces on the body and mind is complex, and not every health-care worker encountering a patient will arrive at the same diagnosis.

As an adolescent, Jordan could sometimes be “off” — raging, depressive, introverted, distractible — but no one who knew him when he was young would have called him severely mentally ill. Yet by January 2013, when he was 20, Neely was telling police on 145th Street that his body was numb and he was hearing voices. Blizzard believes Neely had the seed of mental illness in him since he was a child, especially after what happened with his mother, but what pushed him into his steep decline was K2. “He always smoked a little weed, a little regular weed,” Blizzard says. “But someone gave him that K2 stuff — that’s what fucked him.”

Hospitalizations from K2 began to surge in New York around 2012. A “synthetic cannabinoid” that can be composed of hundreds of different compounds, K2 is sold as a cheap alternative to weed, often under the counter in bodegas and dollar-pizza joints as well as in parks and on street corners. K2 is hard to detect in urine tests, it can be extremely addictive, and it doesn’t metabolize in the body. Outreach workers and psychiatrists who encounter and treat people with chronic homelessness say nothing in the past decade has changed their jobs more than K2, which can make people aggressive, paranoid, delusional, psychotic, or depressed and totally inaccessible — presentations indistinguishable from schizophrenia and other mental illnesses until sobriety kicks in. Starting in 2016, Neely was arrested on K2-related charges at least twice.

In April 2013, a subway passenger captured Neely on video. He was wearing one of his Michael Jackson jackets, red with gold trim, and a gray fedora pulled over his brow, but the wig was missing and he was unshaven. He was standing, balancing without holding on to a pole, and hollering. “You’re a fucking asshole,” he said. “You’re a cocksucker, and you’re fucking cheap. Yeah, I said it. I said the shit. I said it. You’re fucking cheap, man.” The people on the train looked at their laps. Six months later, a student posted a warning on Reddit: “Try to stay away from the Michael Jackson impersonator if you see him … Used to be all cool, dancing to MJ in the subway train, but as of late he’s become a maniac.”

The last time Moses Harper saw Neely, it was 2016, and posts were circulating on social media among the Michael Jackson tribute artists: Has anyone seen Jordan? They were both on the D heading uptown. Harper was seated and looking at her phone, and Neely entered the car through the door between trains. He was panhandling, and she recognized him. “I had never seen him like that,” she says. “He was homeless homeless. The clothes, the aroma, the whole thing.” Neely recognized her, too. At first, he appeared happy to see her and then he looked down, as if recollecting the shape he was in, and tried to avoid Harper’s eyes. “The shame hit him,” she remembers. “And he kind of tried to walk past. He thought I was going to be ashamed to hug him. And I said, ‘Oh, no. You’re not going anywhere. You’re getting off at the next stop with me.’ ”

Neely agreed, and at 161st Street, Harper bought him some fried rice, chicken wings, and a Sprite.

“When you’re ready to get clean, come to me. I have your back,” she said.

“No, no, I’m going to do it. I’m going to get it together. Trust me,” he replied.

Schizophrenia often manifests in late adolescence. Neely had been in and out of shelters, jails, and hospitals, and he told Harper that, according to doctors, he might have schizophrenia.

“What do you think about that?” Harper asked.

“I don’t know,” Neely answered.

Harper gave Neely some money and the warm shirt she was wearing. He was lucid, she says: “Rational. Having a conversation. There was so much sorrow in his voice because we had never been in each other’s presence with him in that condition, and he was so ashamed. It was so heavy on him.” That was the same year his arrest record started to chronicle him exposing himself to subway passengers, revealing the “intimate parts of his body in a lewd manner” to a woman at 4:30 a.m. at the stop by Columbia University, according to court documents, “using his hand to stroke his penis in an up and down motion in plain view.” He would be arrested for this at least two other times.

An army of hundreds of outreach workers — often in their 20s and employed by small nonprofits contracted with the Department of Homeless Services — fans out into the city each day in teams, attempting to make contact with the more than 3,000 homeless individuals who live on the streets and subways. They distribute water, Narcan, and baby wipes. They work in zones, assessing the physical- and mental-health needs of the people on their turf as well as their inclination to accept treatment or housing. If clients do want help, the outreach workers try to connect them with it. The DHS’s tracking tool, an enormous database called StreetSmart, tabulates each worker’s interaction with each unsheltered person, along with any notes, observations, or outcomes. The community organization with the exclusive city contract to do homeless outreach in the subway — all 472 stations and 665 miles of track, including trains, platforms, and tunnels — is the Bowery Residents’ Committee, or BRC. Because Neely lived mostly belowground, he fell under BRC’s purview. The StreetSmart record of BRC’s encounters with him is 71 entries long, dating back to a warm, clear June night in 2017. It was 4:26 a.m., and Neely was at the 181st Street stop on the A. “Mentally ill,” the worker wrote in his notes.

The early records show Neely on trains uptown, near where his family lived, or at Penn Station, close to where his mother once worked, frequently sleeping or “malodorous.” He welcomed offers of help as often as he rejected them; between September and December 2017, he accepted placement at a safe-haven shelter three times. Safe havens are designed as alternatives to traditional shelters; they are smaller with looser rules about drugs and alcohol and less stringent curfews, the city’s attempt to provide temporary accommodation for people who are too vulnerable to survive in rough, densely populated settings like Bellevue. He saw New Year’s Day 2018 from a safe-haven shelter in the Bronx.

Within a year, Neely had moved downtown to the subway stations on the Lower East Side and in the East Village near or on the F line: Second Avenue, Delancey Street, Bowery, Broadway-Lafayette. People who are homeless often find the longer subway lines more accommodating because they provide the most uninterrupted sleep, and the F, at 27 miles, takes more than 90 minutes to travel from end to end. Many gravitate toward the Second Avenue stop for its expansive, lobbylike entrance, which offers both a roof and a gathering place, and because of its proximity to Sara D. Roosevelt Park, a pit stop for drug dealers and their customers, and the East Village, which is thick with shelters, soup kitchens, food pantries, and treatment centers. Gerry Howard, who lived in the subways and tunnels for many years, told me the subways felt comfortable to him and safe from the judgment of family. He used crack cocaine, and “when you get your drugs, you don’t want to be bothered,” he told me. Underground, “nobody’s down there but other homeless people, other drug addicts. You’re in your own element.”

Neely was growing sicker. In April 2019, BRC outreach workers noted his hair was matted and his skin discolored. On June 14, he was taken to Beth Israel hospital for a K2 overdose and “heart and psych issues.” On June 21, he was on the J train, where a worker noted “feces” and “inappropriate clothing.” Six days later, at the West 4th Street station, he punched a man in his 60s named Filemon Castillo Baltazar in the face while he was looking at the train-arrival monitor. That fall, BRC workers noted that Neely seemed “confused/disoriented.” That was the year the Department of Homeless Services launched its “Top 50” list. Many of the people who live in the subways are well known, by face and name, to the police and MTA workers as well as to BRC, and the Top 50 are among the thousands of street homeless most at risk of needing psychiatric intervention, according to the city’s assessment, and who might qualify for and benefit from an involuntary stay at Bellevue or another psychiatric hospital. Among homeless advocates, the Top 50 list is controversial: It seems to make homelessness a crime, punishable by detainment. Neely was on it.

Neely didn’t tell his great-aunt Mildred about his stays in shelters and hospitals, but sometimes he would show up at her apartment unannounced. She would make him a big meal, throw away his clothes, and buy him all new. But Neely did stay in touch with Blizzard, and when he was admitted to Bellevue in March 2020, he called him. “I’d say, ‘When you get out, Jordan, you going to do your dance?’ He’d say, ‘Yeah, yeah. I’m getting there.’” The social worker at the hospital would call Blizzard and he would put money into Neely’s account: “I said, ‘Is he going to be all right?’” But Bellevue’s job is to stabilize psychiatric patients, not treat them long term. The average length of stay there is about two weeks, and as the pandemic settled on the city, the supply of psych beds contracted when hospitals gave them over to covid patients. Before too long, Neely was back on the street, and “we couldn’t find him,” Blizzard remembers. Homeless-outreach teams were scaling back. That July, Neely was spotted on the Delancey Street–Essex Street platform, shirtless and wearing colorful running shorts and one black shoe. At two in the morning on an August night, he was taken to Queens General Hospital.

Anne Mitcheltree has lived in the East Village in the vicinity of the F line for nearly 50 years, and she encountered Neely in June 2021 on a Saturday afternoon, the same day she saw a movie in a theater for the first time in more than a year. After the matinee, she decided to stop at her local store, the S.K. Deli on Second Avenue. Neely was standing in front of the grill counter staring at the prepackaged fruit. He looked emaciated, and his T-shirt was filthy. Though six feet tall, he gave her the impression of someone much smaller, almost like a child. As Mitcheltree stood at the counter getting ready to pay, Neely approached and stared at her. He said nothing, but what she saw frightened her. “His face was frozen. His eyes were glued open, but there wasn’t anybody there,” she says. “He had a small smile on his face.” She turned her face away from Neely to break his stare, and that’s when he hit her on the right side of her head above her eyebrow. Mitcheltree fell backward, landing gently on a low pallet stacked with bags of sliced bread. Neely ran.

Mitcheltree was rattled and upset, but she did not think about calling the police. “You would get a worse injury if you tripped over a pothole,” she says. Mitcheltree, who was 63 at the time, works as a dance therapist at a nursing home in East Harlem run by New York Health + Hospitals, and she is familiar with mental illness in all its varieties: “It didn’t take a genius to see that he was very sick.” She changed her mind after a conversation with her friend who works in a homeless shelter. He convinced her that for the safety of all, including her attacker, she needed to report it to the police.

But in the 36 hours between Neely’s assault and Mitcheltree’s police report, Neely had vanished. On November 12, he struck another woman in her 60s in front of the Bowery Ballroom, causing her to fall down and hit her head hard on the pavement. Two civilians chased him and tackled him to the sidewalk, restraining him until the cops arrived. The two incidents were rolled into one charge. Neely had a long rap sheet, mostly from his early days as a dancer, for turnstile jumping, littering, and moving between cars. Now he was facing felony assault and up to seven years in a state prison. He called Blizzard from Rikers. “I think I hit a lady,” he said. “I didn’t mean to do it.”

That fall, Rikers was at its nadir. The intake pens looked “like Amistad,” according to Rachael Bedard, a physician who worked there until 2022. Without toilets, men were standing in their own excrement. “There’s tons of drugs, but people are also withdrawing. There are fights breaking out,” she says. During the pandemic, about a quarter of the Department of Correction staff was on sick leave and those who showed up to work were increasingly overseeing the detainees by video, rather than walking the floor. The court system had nearly ground to a halt.

Roughly half of people detained at Rikers suffer from some mental illness, so the jail, by default, functions as the largest psychiatric-treatment center in the city. For most of his 15-month stay at Rikers, Neely lived in a “mental-observation unit” intended to provide psychiatric care to detainees too vulnerable to live in the general population but not ill enough to need 24-hour oversight. The units house about 30 men, all with a designation of M (mental illness) or SMI (severe mental illness). Neely was SMI. He lived in a large, open dormitory-style room with dozens of beds.

A team of health-care providers visited the unit every day, checking in with each man for five minutes or so, doing scheduled weekly one-on-one therapy, and sometimes offering art therapy. A few times a day, a pharmacy technician would stand at a window and call “meds,” and the inmates would line up to receive their prescription drugs.

Neely was beloved by the health-care staff at Rikers. He was quiet and could frequently be found lying on his bed. In an environment that breeds conflict, paranoia, defensiveness, and violence, Neely was gentle, earnest, and stable. He smiled and said “Good morning,” according to mental-health-care workers on his floor. K2 is everywhere in Rikers, but Neely was not a habitual user, nor did he get into fights. He took his prescription medication. He enjoyed art therapy and did his homework, filling out worksheets to help him learn cognitive behavioral techniques. There was something innocent and vulnerable about him, people who knew him said, which made him extraordinary. He engaged in therapy — rare in Rikers — and openly hoped it would help him. He would say, “Oh, I just don’t know if I’m making friends here,” one Rikers clinician told me. He occasionally did his Michael Jackson routines in his tan scrubs when the art therapist brought in a boom box.

The mental-health-care workers I spoke to at Rikers believe jail is more destructive than restorative or healing. (“I identify as an abolitionist,” one of them told me.) But they acknowledge the paradox. Neely was someone who “did better in jail than on the streets,” says the clinician. At Rikers, at least, “he was not totally on his own.”

On February 9, 2023, Neely stood before Judge Ellen Biben on the 11th floor at 100 Centre Street. He had taken a plea in the 2021 felony assault, and his case was being heard in the novel “Alternative to Incarceration” court. Established in 2017, the ATI court has a “problem-solving” mission, connecting eligible defendants who have knotty issues related to drug use, mental health, or criminal history with a wide range of individualized therapeutic or supportive programs — housing, residential detox, anger management, outpatient therapy, medication compliance — in exchange for a guilty plea. The deal, Judge Biben reminds each defendant, is this: Adhere to the mandated program and the felony is erased from the record; ditch, rebel, or fail to follow its rules and the defendant will be sent upstate to serve their sentence.

Everyone — Neely’s lawyer, the state’s prosecutor, the judge, Neely himself, and the victim — had agreed he was a good candidate for the ATI court. Although he had been arrested for a violent crime, that behavior was related to “substance abuse and treatment noncompliance with mental-health medication,” the court record said. If he took his prescription meds and stayed off drugs, Neely could be stable. The plan was to conduct Neely directly from the court to Harbor House in the Bronx, a residential facility that specializes in treating people with co-occurring mental illness and drug issues.

After Neely was sworn in, Biben faced him.

Did he understand that he was pleading guilty to a class-D felony?

“Yes,” Neely said.

“Are you pleading guilty because you are, in fact, guilty?”

“Yes.”

Biben set forth the terms of the agreement, then asked Neely if he had left Rikers with his belongings. Neely said he didn’t have any. He was free to go. “You are going to be escorted” to the program, the judge told him. “But you actually have to go, physically and mentally, make it to the program, and commit to being in the program. Do you understand what I’m saying?”

“Yes, I do,” Neely said.

“This is very important,” Biben said. “Because if you leave the program, if you are discharged from the program, if you are out of touch with us, we will not be able to help you, and I’ll have to issue a bench warrant for your arrest. Understood?”

“Yes,” Neely said.

Once out of jail, Neely was “forced back into a world that was exactly the same as when he left,” says a mental-health-care provider at Rikers, a world of scarce options, where the left hand is out of touch with the right, where payment and insurance rules are byzantine and constraining, where well-meaning stakeholders disagree about the best path forward. From Harbor House, Neely had limited contact with the outside world. Its doors are not locked because it is not a prison — and because Medicaid will not pay for psychiatric treatment within a prison setting. Neely left Harbor House on February 22, 2023, less than two weeks after entering.

The reality for Jordan Neely and others like him is that he needed more intensive care than is available in any voluntary inpatient or outpatient program, and he required a more therapeutic kind of attention than exists in any locked one. The state can’t imprison people who aren’t criminals, and it can’t turn mental illness and drug dependence into a crime, a conundrum at the nub of every facile political dispute pitting the civil rights of people with homelessness against perceived threats to public safety. “There should be some transition from Rikers that maybe has a secure element to it but is also therapeutic,” says a person who met Neely during his stay in Rikers. “We’re killing ourselves to jerry-rig what doesn’t exist because it’s too much of a hot potato to talk about any kind of secure, residential, therapeutic environment.” Blizzard is clearer about this: “When he got locked up, that could have saved him.”

Biben issued a warrant for Neely’s arrest on February 23, and people went looking for him. A state-sponsored support team was out looking for him, as was BRC. But outreach workers don’t like the police and are not inclined to work with them, so when BRC encountered Neely twice in March, he wasn’t turned in. Once, a BRC worker saw him riding the train but was off duty and, in compliance with BRC rules, did not engage. Another time, BRC found Neely at the end of the A line at 4:30 a.m. “Sleeping upright,” the worker’s notes said. Neely accepted BRC’s offer of shelter that night and a ride to a converted Days Inn in the Bronx, but he left the next day before any paperwork could be completed. Blizzard ran into him too that spring, on the D train near 181st Street. He looked “dusty,” Blizzard remembers. “Like he was going through hard times.” Blizzard gave him $20 and bought him a sandwich.

In the middle of every night, BRC workers engage in an “end-of-line operation.” They station themselves at a subway line’s last stop and try to remove people who are homeless from the trains and take them to shelters — or hospitals, if needed. The Stillwell Avenue–Coney Island stop on the F is an enormous outdoor station with metal staircases that descend to the blocks below; it’s teeming by day with tourists and visitors to Nathan’s and the Wonder Wheel and deserted by midnight. Each train, as it pulls in and waits to be cleaned and taken out of service, looks like a sleeper car to the underworld. Men who are homeless, spread out two or three per car, sleep in otherwise abandoned carriages, some hunched and covered with blankets, others laid out and wearing their shoes from work. On April 8, 2023, at 3 a.m., one of these men was Jordan Neely. A BRC worker encountered him there but didn’t recognize him.

Neely was standing in the car, yelling, aggressive, and belligerent. When the BRC worker tried to engage him, Neely exposed himself and urinated in the train. The BRC worker called over police, and Neely shouted, “Just wait until they get here. I got something for you, just wait and see.”

In the encounter that followed, no one checked for a warrant. No one enlisted the help of the team’s nurse who was on the platform and had the authority to admit people involuntarily to the hospital. After some arguing, the NYPD did get Neely to agree to go to a shelter, but then the transport-van driver said he couldn’t be alone with him, and while the cops were off looking for a BRC worker to accompany him, Neely disappeared down the big metal stairs and into the night. In his notes, the outreach worker wrote, “He could be a harm to others or himself if left untreated.” The next day, when the worker showed photos of the incident at a meeting, the mistake became clear. Neely was gone again.

On May 1, 2023, Jordan Neely almost missed the F train that was carrying Daniel Penny, a former Marine, on his way to the gym. It was almost 2:30 in the afternoon, and when the train stopped at Second Avenue, Neely ran toward it as the doors were closing and stuck his hand into the gap. The doors opened, he got on, and he began yelling. Neely’s last words, in addition to howling about his hunger and thirst, were “I don’t mind going to jail and getting life in prison” — perhaps an acknowledgment that he had violated the terms of his release, perhaps a plea to be back in a place where meals and medications were provided, perhaps a sign of his exhaustion or anguish, perhaps an admission of defeat. When the police called Blizzard to inform him of Neely’s death, he interrupted the detective before he could even say the words. “I already know,” he said.

A carful of passengers watched as Penny strangled Neely on the floor. A smartphone video captured their struggle and its aftermath: When the train halted at the Broadway-Lafayette station to wait for police, most of the passengers disembarked, but as Penny brushed the dirt off his pants and looked for his hat, a woman stood by Neely’s motionless body, texting on her phone. It was this bystander video, a snuff film, that outraged and divided the city when it went viral the following day, divisions exacerbated by Mayor Eric Adams’s remarks that seemed to absolve Penny and blame Neely for his own death. “Any loss of life is tragic,” Adams said. “However, we do know there were serious mental-health issues in play here.”

The Broadway–Lafayette Street station the day after Neely’s death. Photo: Steven John Irby

By the time of Neely’s funeral on May 19, the city had faced off in all the familiar ways over what his death meant. Leftists furiously posted about systems and structural failures and the unconscionable lack of affordable housing, while the law-and-order constituency linked homelessness to a constant threat of random violence, calling Penny a Samaritan and a hero. The Reverend Al Sharpton presided over Neely’s white coffin blanketed with roses, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, in the front row, stood with her hands in the air, immersed in the call-and-response. After Neely’s casket was loaded into the hearse, a crowd on the street holding signs chanted, “Say his name,” but it wasn’t too long before his name was forgotten and the rubberneckers moved on.

Blizzard says if he had been in the car that day, he would have stomped on Penny’s head. Gerry Howard, the formerly homeless man, thinks Penny was on some kind of ego trip, presuming he had the authority to demonstrate how to deal with people who appear menacing to others on the subway. Howard watched the video multiple times: “He had to keep choking? I could see the muscles in his face and neck. Disgusting.” It took Moses Harper a while to watch the video. “I was in a state of disbelief,” she says. “What do you mean, ‘They choked him to death’? They choked him to death? And when I did watch it, it broke my heart, and not because people stood around and watched. He was always slim, but I had never seen Jordan that small before.”

It’s hard for Carol Kasse to think about how Neely died, on the floor of a subway car at the hands of a stranger, and devastating for her to consider that Jordan died just as Christie had, in the choke hold of someone much stronger and more powerful. But Kasse has found a way to comfort herself when those thoughts visit her, as they do again and again. “I’m very spiritual,” she says. She believes Christie “came back for her baby in the only way she knew. Because she saw her baby suffering. The last thing she remembered was being strangled. And that’s how she came back to take her son.”

This article appeared in the January 1, 2024, issue of New York Magazine.

Photo Credits:

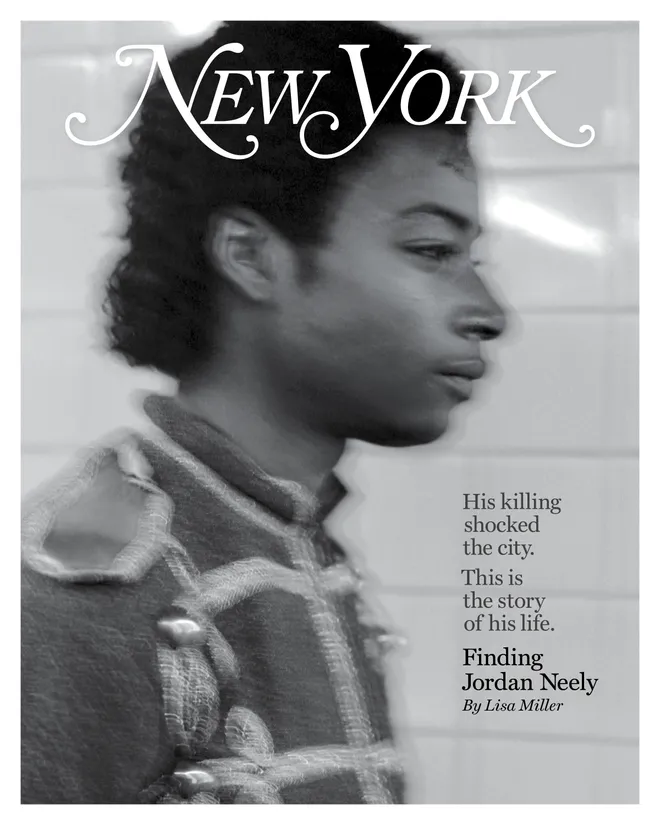

New York Magazine Cover Story

Jordan Neely, Michael Jackson Impressionist. Photo: Courtesy of Humans of New York

Christie Neely, Jordan’s mother. Photo: Courtesy of Andre Zachery

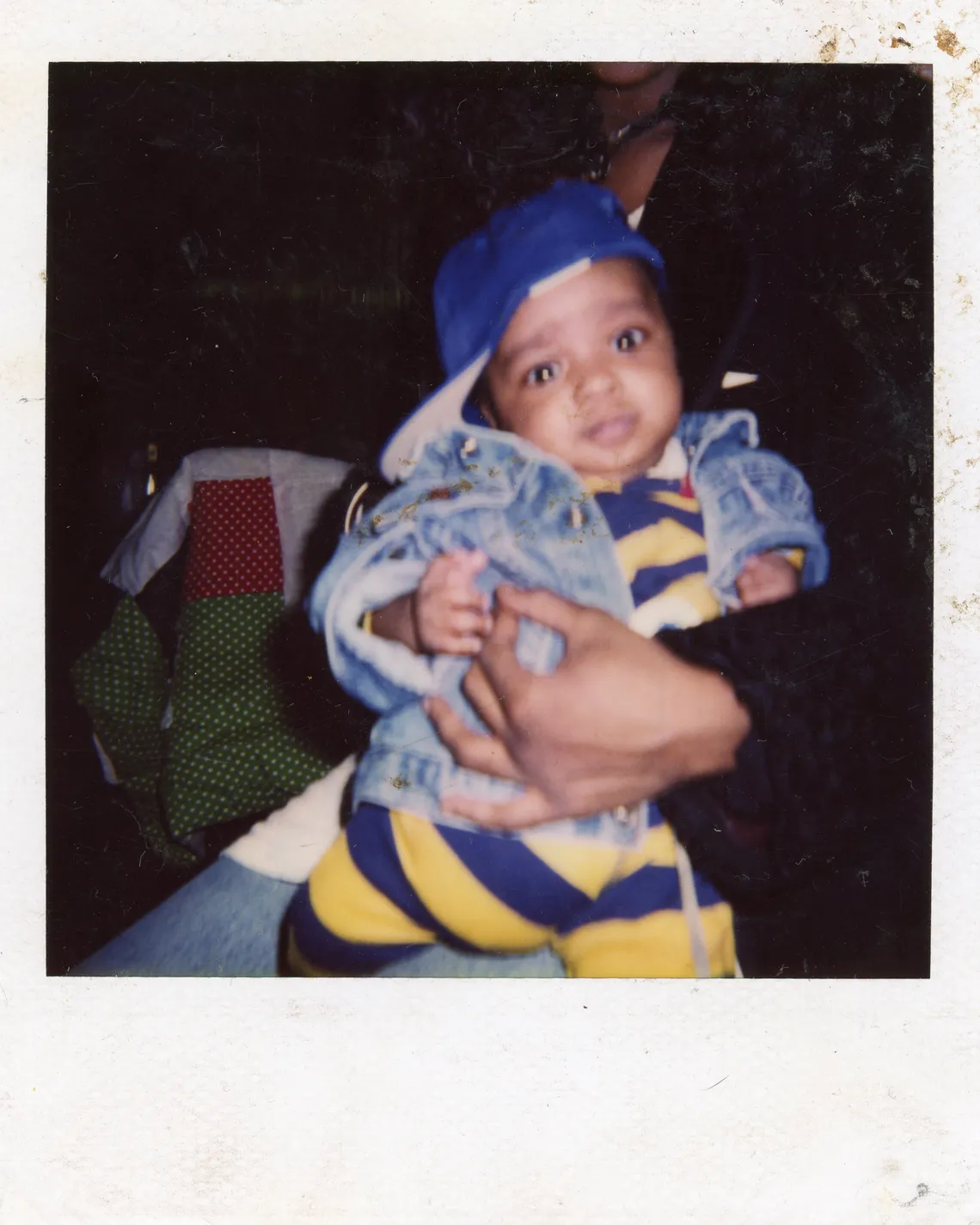

Jordan Neely, age 5 or 6 months, in his mother’s arms. Photo: Courtesy of Mildred Mahazu

At age 3, at Orchard Beach in the Bronx. Photo: Courtesy of Mildred Mahazu

At age 6, with Great-aunt Mildred and Aunt Carolyn. Photo: Courtesy of Mildred Mahazu

At age 8, in Great-aunt Mildred’s apartment building in Harlem. Photo: Courtesy of Mildred Mahazu

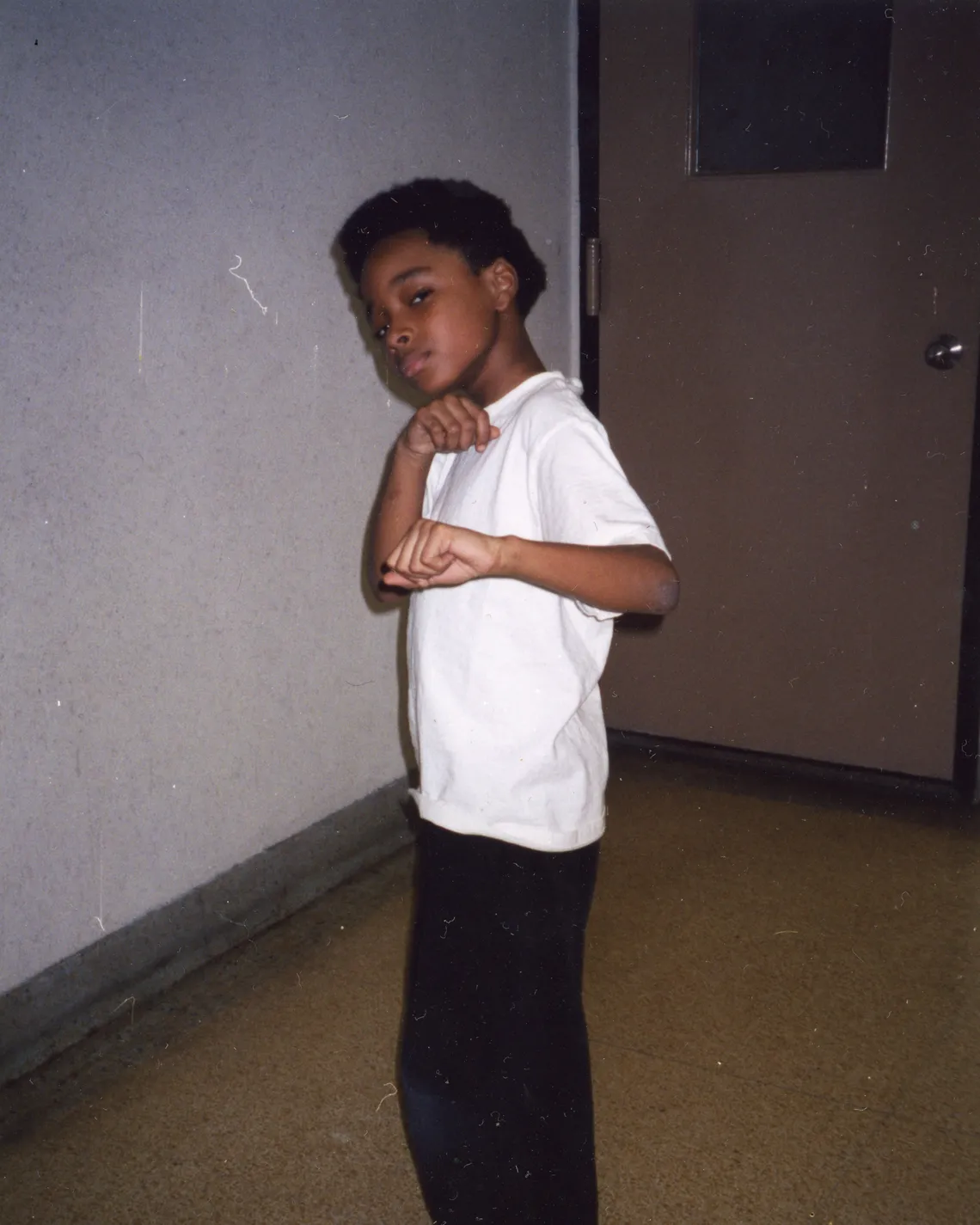

At age 15. Photo: Courtesy of Andre Zachery

At age 26, with his father, Andre Zachery (top left), his aunt Teresa, and cousins. Photo: Courtesy of Andre Zachery