The 10,000 residents of Flat Rock, Michigan, are cheerful lately — you might even say optimistic. Fifteen new businesses have opened in the past year, including Blue Heron Trading Company, a candle-scented gift shop selling local jams and jellies, and a Burger King franchise directly across the street from the Ford Motor Company assembly plant, which the town mayor, a baby-faced 43-year-old man named Jonathan Dropiewski, enthusiastically calls “a license to print money!” There’s a spanking-new Meijer big-box store, which last summer hired more than 300 people, and dozens of new homes have been built, mostly in subdivisions, some selling for north of $350,000. All this blooming industry and prosperity was a matter of fact even before Donald Trump took up the cause of Flat Rock, and other industrial towns like it, relentlessly targeting and humiliating Ford for shipping jobs overseas — ultimately shaming the company into adding 700 jobs to the Flat Rock plant. Which, politics aside, seemed to be the culmination of a very good year. That mood was dampened when, on May 15, it was reported that the company would be cutting about 10 percent of its white-collar jobs in North America and Asia.

The small towns encircling Detroit resemble nothing so much as feudal villages: grids of neat, one-story workers’ homes growing up around a great manufacturing plant. Ford operates 14 factories in Michigan; Chrysler and General Motors, a dozen each. Auto-industry economists calculate that one new automaking job has a multiplier effect of between five and seven, meaning that one new worker at Flat Rock begets five to seven additional jobs: glass workers, steel workers, and truck drivers to service car production; fast-food workers and auto mechanics and hotel clerks to service the workers themselves; robotics and AI engineers who consult at HQ. “Is Flat Rock dependent on that plant?” asks Dropiewski. “Absolutely it is.”

So when, as Trump launched his presidential campaign, Ford announced it was moving the assembly of its Focus, a fuel-efficient economy car, to a plant the bosses would build in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, it tapped into a latent dread — especially 22 miles north, in Wayne, home to the Michigan Assembly Plant, where the Focus is made. Trump seized the moment, making Ford a villain on the stump and relentlessly harassing the company on Twitter. During a visit to Flint in September, the would-be president excoriated the company: “They’ll employ thousands and thousands of people not from this country, and they’ll sell the cars right through our border.” In the first presidential debate, Trump called NAFTA “one of the worst things that ever happened to the manufacturing industry,” and when Hillary Clinton responded to Trump dismissively — “Well, that’s your opinion” — “our hearts went through our chest,” says Brad Markell, executive director of the AFL-CIO Industrial Union Council. In the industrial Midwest, NAFTA is shorthand for everything bad that has happened to manufacturing over the past 25 years. The United Auto Workers endorsed Clinton, but in Flat Rock, the residents went for Trump.

Ford executives were thin-skinned about the critique, and who could blame them? This was a great American company, an iconic brand, the only one of the Big Three auto manufacturers that did not declare bankruptcy in 2009 (though it survived thanks to a government loan). By 2016, Ford was posting record profits — $4.6 billion that year — and hiring new people, so initially it held the line. “Ford has more hourly employees and produces more vehicles in the U.S. than any other automaker,” it tweeted in its own defense. But last summer, Bill Ford Jr., Henry’s great-grandson, paid a call to Trump Tower, and in January, the company seemed to cave, announcing it was ceasing construction on the San Luis Potosí plant, even though cement had already been poured. Over the next several months, the details — many of which Ford and the union said were long planned — became clearer. Ford would still move the Focus to Mexico, but the car would be produced in an existing facility in Hermosillo. Wayne would get the job of producing the new Ranger and the new Bronco, which the company hopes will satisfy Americans’ revived appetite for bigger cars. And Flat Rock would get 700 jobs and the honor of launching Ford’s new “autonomous” car.

The reversal was especially big news in Wayne, where, compared to Flat Rock, prospects are bleak. As recently as 2010, the Focus, Wayne’s chief export, was positioned as a cornerstone of the company’s revival, the answer to demand for inexpensive, stylish, fuel-efficient, “clean” American cars that could compete with the Kias and Mazdas flooding the market. But that was when gas was creeping toward $4 a gallon. When fuel prices plummeted to around $2, Americans reverted to their old habits. The F-150 truck, always the best-selling pickup in the country, became Ford’s cash machine. Dealers said they couldn’t keep Ford’s giant family SUV, the Explorer, in stock; meanwhile, the plant in Wayne had dropped from three to two shifts, and in 2015, Ford had laid off 600 workers (though, since the union requires Ford to rehire these workers if it expands again, most of them were eventually brought back on).

The mayor of Wayne, Susan Rowe, is an exhausted-looking 67-year-old woman who in 2015 retired from her paying job as an executive assistant to try to save her town, where she’s lived for 27 years. Rowe carries on her narrow shoulders the whole legacy of the auto industry. Once largely living off the taxes Ford paid on its plant, Wayne is in a seemingly unstoppable downward spiral. When Ford went into the business of saving itself, it slashed costs ruthlessly, and, in 2009, the Big Three lobbied Lansing to change tax rules to benefit themselves, depriving factory towns of revenue they had come to depend on. Rowe says tax revenue in Wayne dropped by 50 percent. Finding the money to pay the bills has become like “squeezing blood from a turnip,” says Rowe. The population is shrinking, and poverty and petty crime are on the rise, according to Rowe. So the fact that Ford has decided to keep Michigan Assembly Plant open leaves Rowe underwhelmed. A business that must constantly cut costs to boost its stock price — as evidenced by the layoffs this week — cannot also keep the best interests of the municipalities that serve it in mind.

The City of Wayne still owes Ford around $500,000 from an old tax dispute. Without a real infusion of jobs, or new construction at the plant, Ford’s promises won’t generate much additional revenue and thus won’t materially improve Rowe’s balance sheet. She’s already laid off more than 100 municipal workers and put the fire department’s ladder truck up for sale. “These automotive companies, they have a right to make a profit and earn a living, but I’m sorry. When you think about Ford Motor Company, we owe them half a million dollars, they made $5 billion in profit last year. I mean, what is half a million going to matter to them?” Last month, Rowe voted with the City Council to eliminate health insurance for municipal retirees — the hardest vote she’s ever cast, Rowe says. “A lot of those people that I’m doing this to are friends of mine. It’s very difficult. But yet, I’m trying to save a whole city. Somehow. And it’s very hard.”

In 1978, the American auto industry employed 1.2 million people; by 2009, that number had been reduced by half. It’s not personal, and there’s no single culprit. Competition, especially with the Japanese, toppled the Big Three’s primacy. Automation eliminated whole categories of jobs. Globalization forced consumer prices down, putting crushing pressure on automakers to continually cut costs. These forces have devastated the American industrial-labor market over the past half-century, like oceans rising and flooding the landscape. The jobs that remain are a mixed bag. Some are appealing: in management, engineering and robotics, industrial design, and even machine learning. And union workers on the line can still earn about $30 an hour. But thanks in part to the decline of unions and the ever-increasing (market-driven) corporate focus on profit margins, assembly jobs are no longer as stable or as lucrative as they once were, and the vast majority of autoworkers — 72 percent — now work in separate auto-part plants, most of them as independent contractors often doing dirty, dangerous work for significantly lower pay. So when Donald Trump tweets “JOBS! JOBS! JOBS!,” as he did in March, taking credit for Ford’s moves in Wayne and elsewhere, he is marketing a nostalgic fantasy of a time when a job at Ford meant a house, a boat, a pension, and a backyard grill.

But time doesn’t go back. The Ford of 2017 wouldn’t survive if it hired a hundred thousand Americans to work its lines or reinstated lifetime benefits for those it does employ. Its factories are already making as many cars as people want to buy (and maybe more), and a new generation of competitors like Tesla and Google promise to change the game — again — completely. So what help is possible? Can a president really bully penny-pinching American corporations and lawmakers into crafting an industrial policy that will genuinely benefit workers and a region where people eat with their paychecks — can he turn towns like Wayne, that is, into towns like Flat Rock?

On the margins, the answer is, actually, yes. Especially in the wake of the election, economists have been looking at places like Wayne and considering what public policy could accomplish. “What can we do to make sure that regions and workers as well as multinationals share in prosperity?” asks Susan Helper, formerly the chief economist in the Obama Department of Commerce. NAFTA might be revised to support raising wages and stronger unions and environmental and workplace rules in Mexico, thus eliminating the reflexive reliance in the U.S. on its bargain-basement labor costs (and also creating a class of Mexican consumers who could afford to buy the cars they built). Tariffs might be imposed on “American” products made in foreign countries or with too many foreign parts. An increase in the gas tax would raise fuel prices, creating a budget for infrastructure development (roads, for example) and a real market for fuel-efficient and electric cars. Tax breaks could encourage corporate expansion. Governments might look at places like Southeast Michigan and build social supports — at least for the younger generation, so the children of defeated workers don’t grow up into defeated adults. All these “solutions” have their detractors, of course, many of whom see the proposals as contradictory or counterproductive. Few economists agree that good policy is the true objective of Donald Trump, who often veers between rhetorical populism and plutocratic allegiance. And even in 2017, the auto business is fundamentally the same business, facing the same problems as before. “There are too many car companies. Too many models. Too many dealers,” says Adam Jonas, an auto-industry analyst at Morgan Stanley. “It’s dog eat dog, and survivalist. That is the world. It’s the way it was. It’s the way it is, but it could be even worse.” So even if, in some fantasy world, Trump were able to implement a coherent industrial-policy strategy, its effect on employment would be rather small; the larger forces are, in the end, much more determinative. Not only is Ford laying off salaried workers, but General Motors is idling plants that make SUVs and pickup trucks for ten weeks this summer.

But in Southeast Michigan, people have to believe in fixes. Around here, “American made” is not a jingoistic slogan evoking an idyllic past but a description of reality: the eight-axle trucks caroming down dilapidated highways at 65 miles per hour carrying loads of steel or aluminum or glass to plants where they will be stamped or molded into cars or parts for cars; the behemoth warehouses storing the metals themselves, each spool at least as tall as a man and weighing about 35 tons; the assembly lines, the backbone of industry, which at Ford produce a car a minute, each one built to spec and delivering in its own way that American right — to own wheels and a full tank of gas. In the parking lot of Local 900, which serves the Wayne plant, a sign reads NO FOREIGN VEHICLES ALLOWED ON THIS PROPERTY.

The car business is a family business, going back generations and across them, too. Jeff Carrier, who manages the Flat Rock plant, grew up in a trucking family. He likes to drink at the Roc after work, a new wine bar where a photo of the paterfamilias, Luigi Fiorelli, who spent 58 years at Ford, hangs up front in a place of honor. The proprietors of Blue Heron just down the street are a Ford family, too: Mark Maul used to work at HQ, and now his wife, Alisa, hopes to rent the apartments she manages to the new Ford people coming to town. (“We joke about it, actually,” she says. “You know, if Ford goes out, we’re all screwed.”) Everyone likes to talk about what they drive: a Mustang, an Escape, an Edge, an Explorer. Among the workers, there’s a pecking order: It’s good to work in a plant that manufactures cool cars, like the Mustang, and better still to work in plants that produce the moneymakers. The F-150 is assembled in the location of Henry Ford’s original plant, at a complex that is also a tourist attraction called the Rouge. None of the people I spoke to in Southeast Michigan is willing to believe that this industry, which their ancestors invented, could go extinct. But it’s also true that the prospect of extinction keeps them up at night.

“I’m a car girl, and I’m proud of it,” says Debbie Dingell, the Democratic representative for Flat Rock in Congress, whose family started Fisher Bodies, an early auto-body-maker, and who now drives an Explorer and a Cadillac. Dingell is determined that solutions can be found and has promised to work with the president on any revision of NAFTA. But she sounds tired. “This is Donald Trump. He says stuff,” she says, sighing. “I have no idea what he’ll do.”

Here’s how Mike Beydoun felt when he heard that Ford was stopping construction on the new plant in San Luis Potosí. “I was happy,” he says, then goes silent. “I thought, Good. Good.”

Beydoun and his wife are raising three children not in Wayne but just outside Dearborn, the center of the biggest community of Arab-Americans in the country. It may seem odd that Dearborn, that seat of mid-century Wasp prosperity, would also have the best Middle Eastern spice shops anywhere on the continent, as well as one of the oldest mosques in the country. But in Dearborn, it’s normal — so normal that even in this racialized, polarized national political environment, Beydoun, a U.S. citizen who has spent his life at Ford, cannot comprehend that some people might regard him as less than completely American. “We’re a moderate family. We’re very Americanized, if you want to call it that. But we follow our religion, so what? That’s a right you have.” He disagrees with Trump’s immigration ban “100 percent,” he says. “I get up every morning and go to work. So, now they’re going to put a checkpoint in?” He’s joking, but only sort of. “The smartest people in the world are immigrants. They come here because of the opportunity. And we want to ban that? That doesn’t make any sense.”

In this way, Beydoun is heir to one of Ford’s proudest corporate traditions, which is that since the invention of the assembly line in 1913, Ford has given good jobs to the people no one else would hire — African-Americans, Mexicans, Irish, the disabled—propelling them into the middle class. Arabs — Syrians, Palestinians, Yemenites, Iraqis — had been in Dearborn from Ford’s beginnings working as peddlers and were lured, along with all the other outcasts, to the assembly line on Henry Ford’s 1914 promise of $5 a day. (And when Trump announced his immigration ban, Ford pushed back, saying, “We do not support this policy or any other that goes against our values.”

Born in Lebanon, Beydoun was part of a wave of immigration that flooded Dearborn in the 1970s, a time when brothers and cousins and uncles got each other jobs just by walking onto the factory floor and vouching for one another. He immigrated as a baby with his mother after his father secured a job at Ford. He became a naturalized citizen in 1981, when he was in the third grade. “I’ll never forget it. The guy asked me one question: ‘Who’s the president?’ I said, ‘Ronald Reagan.’ He goes, ‘Sign right here.’ ” And he remembers the day his father approached him with an offer. “Do you want to work at Ford Motor Company?” Beydoun started out, as a teenager, making $12.50 an hour two days a week, installing brackets on the hoods of Ford Escorts, believing this stint was temporary. “I’m not going to lie,” he says: Ford wasn’t in his plans at all. In college, Beydoun was good at math and hoped to become an engineer. But then he aced Ford’s internal skilled-trades exam and his father wouldn’t hear any arguments. Being promoted into the skilled trades — a plumber, an electrician, a welder, a pipe-fitter — would make him one of the “big shots” in the plant.

For 11 years, Beydoun worked as a millwright, repairing the mechanical guts of the assembly line itself: “structural steel, conveyors, chains, sprockets, things like that.” Now he also works as a union rep, overseeing work issues for the plant’s 200-plus skilled-trade workers. He has been laid off, which, in a cyclical business, union workers come to expect, but the anxiety of those months forced him to reconsider his father, who through the 1980s frequently didn’t work at all. He sees his employer as a beneficent monster — taking advantage where it can, saving pennies by outsourcing jobs not just to foreign countries where labor is cheap but to American shops unconstrained by union contracts, to glass shops and seat manufacturers where wages are rock bottom and work conditions worse.

“If you don’t have the union, they’re going to run all over you,” he says. “We see it. We battle them every day. And it could be the smallest battle or it could be the biggest battle. And they’re always testing. And they always will. It’s just the nature of the beast. They’re going to see what they can get away with, and you just got to figure out where you draw the line.” That’s where the art is, to figure out what you won’t do without negotiating yourself out of a job. “I tell people, ‘You know, there’s things we can’t control.’ And I’ve always been a believer in ‘Don’t worry about what you can’t control.’ ”

Sitting at a round table inside Local 900, Beydoun gives voice to the selfsame fear that must keep his bosses up at night. He works on the Focus, and he knows how slim the margins have been, and while he’s hopeful that the Ranger and the Bronco will light up demand, there’s no way to know. “It’s market, right? So, yeah, let’s get this Bronco and Ranger here. But what if the Bronco doesn’t sell? What if the Ranger doesn’t sell? What if it’s a flop? We don’t know. I think, just by looking at the Ranger, we believe it’s going to be a good-selling vehicle. But you can’t control it. What if the F-150 stops selling? Then what happens to the Ford Motor Company? But you can’t worry about that. Right?”

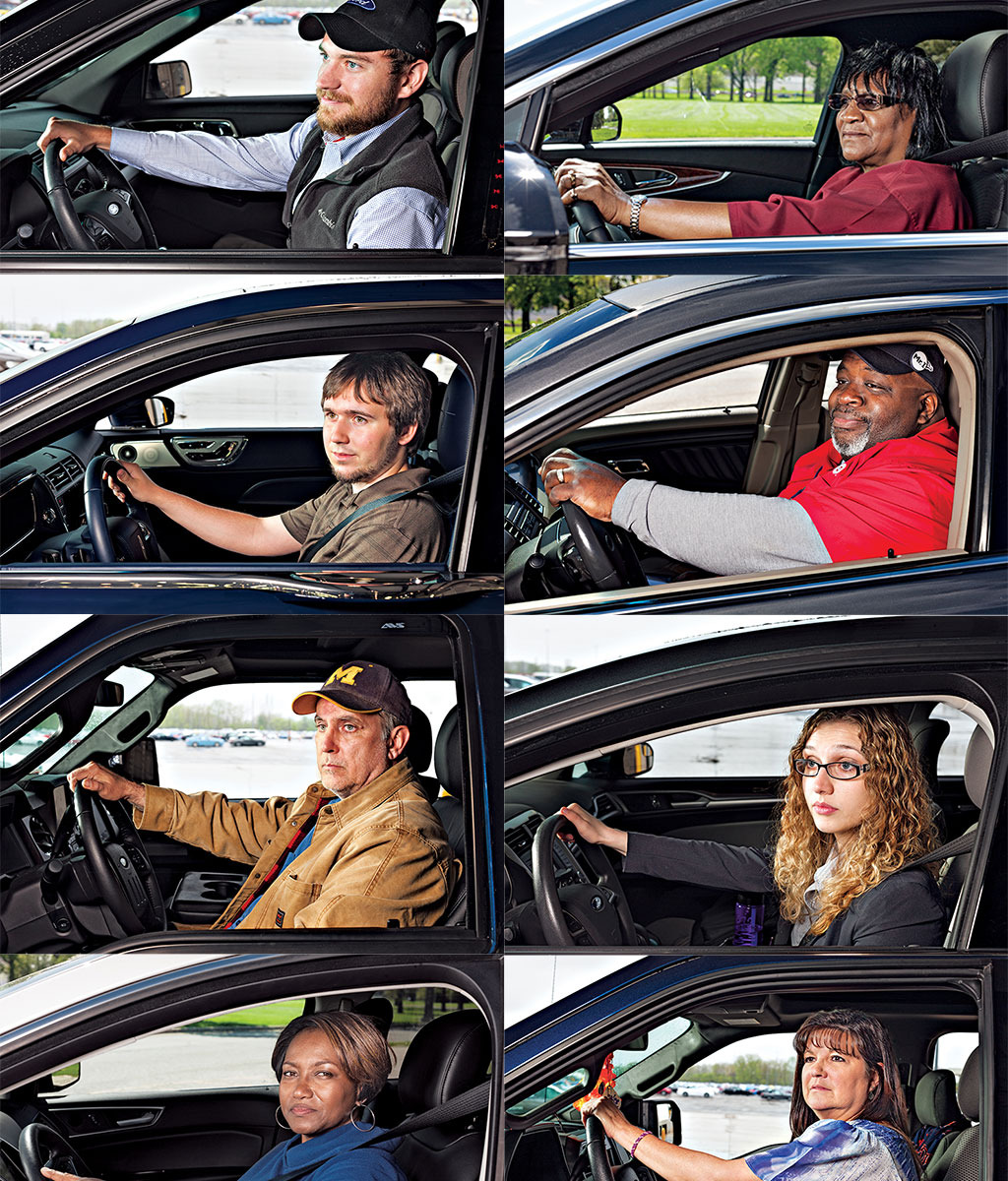

Nothing can prepare you for the immensity of an assembly plant, the place where the body, an empty, painted metal shell, is outfitted with the many thousands of separate pieces it needs to become, finally, a car. Every Mustang in the world is assembled at the Flat Rock plant, the bodies entering, ceremoniously, on a belt up near the ceiling like skeletal birds before they descend to the floor and get their doors removed: an innovation that allows workers to reach inside cars and install seats and seat belts and electronics and carpet without having to twist themselves around protruding metal. Slow-moving conveyors trace the floor, carrying vehicles forward from station to station, 500 in all, each one with workers doing singular, repetitive physical jobs at a pace that’s reasonable and relentless at once. There are men and women, black, white, Arab, Spanish-speaking, young, bearded, obese and cadaverlike. The Flat Rock line currently produces 800 cars a day — Mustangs and Lincolns — one every minute, 16 hours a day, five days a week (not counting breaks).

Automation has improved things, on balance, for those workers still employed. Seats, tires, and windshields that used to be lifted with back and gluteal muscles now rise with the push of a button on hydraulic lifts. Nuts and screws that used to be tightened with giant hand-held power tools now fasten lightly without any kick. A man named Chris Wiley who works at the Rouge used to screw the back seats into the Mustang with a big yellow gun called “the Lion.” “It was about three feet long, and if you didn’t let go in time, it would pull you right into the car.” Workers talk about the way they used to feel after a day on the line — “Shell-shocking,” says Beydoun — and you can see the effect of years in the posture of the old-timers. They hold their large torsos delicately, on spindly legs, as if not to disturb their insides. If some of this automation had been in place when he was younger, “I wouldn’t have the pains and groans and moans I have right now,” Wiley says. He smiles when he says it, but the preponderance of disabled parking spots at the Locals and frequent allusions to drug abuse among workers belie his good humor.

Now, when Ford launches a new car or truck, a Canadian yoga and rock-climbing obsessive named Marty Smets, with a waxed mustache and a master’s in biomechanics and ergonomics, uses computer modeling technology, like CGI, to render a 3-D assembly line peopled by anatomically precise digital workers so that the company knows exactly how far the chassis needs to be from the worker’s knees, how low the conveyor needs to be for a worker to reach easily into the engine, an optimization of speed and efficiency combined with a concern for the human body. The erg team calls longtime assembly workers “our industrial athletes,” says Smets, with admiration. “If you’re on a job for ten years, you’ve done it 750,000 times. That’s four times as many times as I’ve brushed my teeth in my entire life.”

But Smets can get up and pee when he feels like it, without having to pull a cord to summon a replacement. Tolerance for mid-century industrial work has diminished along with the pay, and there’s a generation gap between the old-timers and the newcomers on the line, a difference in attitude about how much the work matters. This is a structural difference as much as it is cultural: In 2007, all the automakers negotiated a two-tier pay system in which entry-level workers earned about $15 an hour, around half the pay of workers with seniority; their benefits were less generous, too. (Since 2015, the union has renegotiated so younger workers can catch up to the wages of their seniors over time, but their benefits remain less enticing.) “There’s a different mentality,” says José Del Otero, an assembler at Ford. “Maybe they’re not as committed. Maybe they don’t have the same bills as I do.”

They also seem less interested. Observing, perhaps, the misfortunes of their parents, they regard these as dead-end jobs, even if they pay pretty well. Paul Russo owns Wayne Industries, a business that his father started with a single tractor-trailer, which stores and ships steel and aluminum to auto plants in the Midwest and the South. The warehouse in Wayne is 580,000 square feet, filled with steel coils, which look like spools of thread, only humongous, each weighing about 40,000 pounds and containing enough to make 16 cars. Russo also owns a fleet of 600 trucks but can’t find reliable people to drive them. “They’re late. They don’t show up. Always have an excuse. And some of them can’t pass the DOT drug-test requirement for the physical.” He can’t keep workers in the warehouse, either. For every ten people he hires, he says, he retains two. “Kids are lazy today. Everyone thinks everything’s done with buttons.” He starts warehouse workers at between $13.50 and $14 an hour, nonunion, and he believes the work is easier than it was when he was young. “I used to do it when we didn’t have all the automatic stuff. When we had the levers and stuff like that. Had to throw chains. Had to throw bars. They don’t do anything. They just sit there. This country’s in trouble.”

A car factory used to make the whole car. That was, in fact, the entire point. One company would buy rubber, sand, and iron ore, then manufacture tires, glass, and steel, putting them all together in the end. As time went on, the automakers realized they could become more efficient if they shed some of these functions by outsourcing them, only assembling finished vehicles in their plants. Then material and union labor were no longer on their books, and other companies might develop specialized expertise. The efficiency has helped Ford grow, but the better word is probably just “survive.” “Costs have always been an issue,” explains Kristin Dzizcek, an analyst at the Center for Automotive Research. But the federal bailout increased automakers’ ferocity — because, as Dzizcek says pointedly, “You can’t go get the bailout twice.”

Mark Schmidt has felt the direct effects of that outsourcing. He runs another family-owned business, Atlas Tool Inc., in another town, called Roseville. It makes the mammoth cast-iron molds (called “tools” or “dies”) needed to mass-produce large pieces of shaped metal: car doors, hoods, trunks, and bodies. Atlas Tool Inc. used to employ 350 people. Now it employs 125.

Schmidt faces a different kind of labor shortage. It’s not that he can’t find enough young people to work in his shop. Tool and die is a good job in the skilled trades. The problem, from Schmidt’s point of view, is China. Schmidt can’t hire young people — or any people — because the automakers have taken so much of their tool-and-die work to China, which creates the tools for between 15 and 20 percent less than Atlas will, even when you include the cost of shipping 30-ton pieces of metal back across the Pacific. So moribund has the tool-and-die industry become that Schmidt estimates that two-thirds of his competitors have closed their doors since 2000. In a contracting industry, young people aren’t entering the field, so most of the people that Schmidt employs are older than 50, a twofold burden: He has to pay the senior people more, and the pipeline has dried up. “It’s difficult to attract people to a dying industry. Why would you want your child to go to a shrinking industry? I have two sons. I convinced them to get away from this industry.” Schmidt is facing the real prospect of an American profession — his own — vanishing completely.

But the Chinese, in Schmidt’s opinion, do crappy work. So when a tool comes back from China and doesn’t produce the door that Ford, or whoever, wants, the automaker calls Mark Schmidt and asks for help. “Chinese tools don’t work right,” he says. “They always — almost always — need to get fixed. To fix errors, bad craftsmanship issues, bad dimensional issues.” Schmidt still gets contracts to build dies himself, but he spends at least half his time fixing Chinese mistakes. Schmidt worked on a lot of the tools for the latest F-150 after they came back from China. “We’d sit down with Ford and say, ‘All these things are wrong.’ We’d make a long list and ask, ‘Which ones do you want us to fix?’ And there would be a cost and timing associated with each one. We’d say, ‘To do all this would take 12 weeks,’ and they’d say, ‘Well, we only have four. What can you do in four?’ We’d have them prioritize which are the most important, and we’d keep going down the list. ‘Okay,’ they said, ‘That’s enough.’ ” (About the plight of the tool-and-die industry, Ford’s vice-president of North American manufacturing, Gary Johnson, says this: “I see a lot of that starting to shift back. It might be cheaper to build them there, but it costs more on the back end.”)

Schmidt’s anxiety is self-interested, naturally, but it’s global, too. What happens to the U.S. automakers when American tool-and-die shops perish? “The Chinese, they don’t just want the die industry. They want to build cars. And they see this as a critical stepping-stone. I don’t know why we don’t see it as that. If you can’t make the dies, you can’t make the car. At all.” If his industry disappears, “then China — or whoever takes it over — can literally control auto production. They might just get the idea, We don’t want Ford to make that car this year. It would help our competitive position if they didn’t make it until next year and we make ours this year.” Luckily, Schmidt has a simple fix: Impose a tariff on imported goods that are sold below cost. “Our industry would come back very quickly,” he says. “We could easily grow. We have all the space. We have all the equipment.”

Of course, if you did that for every industry, you’d be effectively ending free trade, which is not nearly as simple a fix. At Ford, the executives seem less worried about tariffs and more worried about the future of automaking. In an office high above the line at Flat Rock, a Ford manufacturing team, salaried men, are discussing how to move Ford’s first self-driving car through an assembly line.

In the time that I was in Dearborn, I heard Henry Ford compared to Steve Jobs more than once and Ford itself referred to as “a technology company.” In an interview the week before the layoffs were announced, Ford CEO Mark Fields told me that he is hiring untold numbers of geeks who would never have been considered “car people” before, and that the composition of his white-collar workforce would inevitably be changing. “We’re always looking to get as efficient as possible through the core side of our business,” he said. So while the “driving” side of the business is contracting, the “automation” side is expanding. “We’re hiring machine-learning people. We’re hiring behavioral economists. We’re hiring software coders. That’s the kind of talent that five, ten years ago we never thought we would attract to the company.” It’s a gamble. Ford has recently invested $1 billion in an artifical-intelligence start-up called Argo AI. And it has launched a number of experiments aimed at turning the 100-year-old automaker into a place that 21st-century geniuses might like to work. One of these is Ford Labs, a team of mostly sneaker-wearing young men who work in an open-plan office, where the walls are covered with white boards and hot-pink stickies. They’re working on an app for a ride-sharing shuttle, like an Uber minivan, and thinking about how to send a person’s driving data — where he stops for coffee, where he picks up dry cleaning — to his Apple watch.

But these manufacturing executives sitting in this factory aren’t really worried about the data the new car will collect or the various ways Ford might monetize that data. How will a self-driving car, which is still a piece of metal, but with a brain, move through the line? How many parts will it need? Will it even require a conveyor belt? Or will it drive itself from station to station? They are confronting what for them is an existential question — an imaginable future when a car might not just drive but assemble itself. These are car guys. They love driving.

“It’s hard for me to believe that people are going to want a car that you’re not going to drive,” says Jeff Carrier, supervisor of the Flat Rock plant. “I know there’s a need, it’s just a totally different generation.”

“It’s a bit scary,” says Gary Johnson, Carrier’s boss. “We’ve been around for what, 113 years? You know, the modern assembly system has always been a conveyor. This will be different for us. It’s going to be crazy,” he says. And then, on a more positive note: “It’s going to be neat.”

Saturday, April 22, was a beautiful day in Flat Rock, breezy and cool; the whole town, it seemed, was out for the annual Little League parade. Kids representing teams called the Lug Nuts and the Hot Rods marched through the streets, and the local Ford dealership, naturally, sponsored the day.

Down the road, at Wimpy Burger, Steve Marzouq was doing a crazy business. Marzouq, a voluble and high-strung smartass who drives a 2016 yellow Mustang GT with racing stripes and gave his teenage daughter, Tiffany, the 2006 convertible model in red, opened Wimpy’s a year ago, restoring a 1950s lunch counter to an ersatz version of its original self. Cheeseburgers cost $1.54. Marzouq’s father worked on the line at Ford and used to take Marzouq to this restaurant when he was 3 years old. Back then, the place was called M&M.

“Generally, I do about 350 or 400 burgers for lunch,” Marzouq told me after the rush. “Today, 780. It was nuts. I couldn’t believe it. The girl in the back, she’s like, ‘Where’s the meat? We’re out of meat.’ We had four tubs of meat. That’s 200 a tub. Onions: I’m out. I bought a box this big yesterday morning, and we’re out of onions. Usually, the onions, they last us about three days. Onions—gone. Twenty-four hours.” Marzouq, 47, formerly made his living selling used cars, but he grew tired of chasing after deadbeat customers and competing with the dealers who were giving away financing almost for free. So like hipster malcontents in other parts of the country, he developed a retro-service plan B. Wimpy’s, with its throwback style, is Marzouq’s attempt to seize control of the forces that previously ruled his life: the corporate whims, the unceasing selling, the economic cycles that left him rich one year and ruined the next. It’s a new business, with longer hours, but one that — literally, with its jukebox and milkshakes — evokes a calmer, saner way of life. Mostly Marzouq flips the burgers himself; on weekends, Tiffany helps out in front. “Hello, welcome to Wimpy’s,” she says. “Dining in?”

Marzouq saw what a lifetime working assembly did to his dad, an immigrant from Jordan whose own father brought him on the line and who worked for Ford for 40 years, at his peak earning $130,000 a year, before succumbing to a pain-pill addiction that left him divorced and broke. In pursuit of the American Dream, Bill Marzouq “worked weekends. Doubles. He got triple-time on Sundays. Ah, it was great. I never saw my dad.”

In 1990, Bill Marzouq was “hanging bumpers on the assembly line. Back then, we’re not talking plastic. Metal, heavy bumpers. He blew his back.” The doctor gave him a choice. “Either have surgery and you’re off work for four or five months. Or take Vicodin.” Bill chose the Vicodin. For the first few years, he was taking one or two a day. After a decade, he needed 60 to feed his habit, “and that’s the truth. They found him lying flat-faced, naked, so many times.” Steve would get calls from the emergency room, saying his father had called his dealer from his hospital bed.

Bill Marzouq died two years ago, and Steve still doesn’t like doctors or hospitals and refuses to take medicine of any kind, even aspirin. (“Every time I start feeling a little itch,” he said, pointing to his throat, “I take a zinc.”) In fact, it’s fair to say that Steve Marzouq is a skeptic about anyone claiming to know better than he does about what’s good for him. He doesn’t like authority, doesn’t trust the Establishment. He hates all politics and politicians. “Look at frickin’ Donald Trump, for crying out loud. He’s going to start a war with North Korea.” (Then he came clean: He voted for Trump. “He’s a moron. He is. But I had to vote for somebody.”) The car companies are in it for themselves, he says, producing hundreds of cars a day that people don’t need. “The price of a car in 1980 was $17,000. Now the price of a car is $40,000 to $50,000. Who can afford this? You can only build so many cars, realistically. Am I wrong? How many cars does Ford Motor Company build in a day? In a year? Are we buying that many cars? It has to stop, don’t it?”

In the perfect world of Steve Marzouq, a person’s fate would not be tied up with that of an auto-manufacturing plant. But in the perfect world of Steve Marzouq, baseball players would also not earn millions of dollars a year and “an animated idiot” would not be president and his Wimpy Burger stand would not succeed or fail based on whether the suits at Ford can figure out how to build a self-driving car. In the truly perfect world, Marzouq himself might be in charge. My phone was on Wimpy’s lunch counter in recording mode; we had been talking about the cruise he recently took with Tiffany. Marzouq leaned in and spoke. “Look,” he said, “I have a plan. More jobs. Family time. If there was more time for families to be together, we could raise our kids the right way, correct? More time where husbands aren’t screwing around, wives aren’t screwing around. Time to sit down and let’s all have dinner together.

“Here’s my plan. Free education. Schooling — all free. College, everything. Free medical. Let’s pay our teachers, and our police officers, and our firefighters. The right pay. Okay?”

*A version of this article appears in the May 15, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

This story has been updated to reflect the news that Ford is laying off 10 percent of its North American salaried workers.