Will a jury find James and Jennifer Crumbley criminally responsible for their son’s mass shooting?

In July 2022, New York Magazine published “A Handgun for Christmas,” a story about Jennifer and James Crumbley, the Michigan parents charged with manslaughter after their 15-year-old son brought a gun to school and killed four of his classmates. According to a prosecutor’s brief, this was the first time criminal charges had ever been brought against the parents of a school shooter. In September, their trial, scheduled to begin in October, was postponed. At a pretrial hearing on October 24, the shooter, Ethan Crumbley, chose to plead guilty to the 24 charges against him, including first-degree murder and terrorism. He may testify at his parents’ trial, with his sentencing to follow.

On the Saturday after Thanksgiving in 2021, Jennifer Crumbley pushed through the glass door at the Accurate Range. Jennifer, who goes by “Jehn,” appeared self-assured — a tall 43-year-old mother in jeans and a nubbly sweater coat. In her left hand, she carried a black case that held the SIG Sauer 9-mm. semi-automatic pistol her husband, James, had purchased at a gun shop near their home in Oxford, Michigan, the previous day.

The Crumbleys’ 15-year-old son, Ethan, had come along. He stood awkwardly by, glancing distractedly at the semi-automatic rifles for rent on the wall. After consulting with him, Jehn paid cash for half an hour of range time, 100 rounds of 9-mm. ammunition, and two paper targets.

It’s not unusual to see kids at the Accurate Range, which markets itself as a family place. Situated in a shedlike building next to a software firm and across the street from a Taco Bell, the range resembles a suburban bowling alley down to its crowded parking lot and the flashing green-and-red OPEN sign in the front window. Accurate has a party space, and it promotes seniors mornings with free coffee and doughnuts and Mother’s Day with free gun rentals and snacks. It co-sponsors church dinners, and when it exhibits its wares at gun shows, it advertises “kid-friendly outdoor activities, raffles/door prizes, and beautiful wildlife displays.” Under federal law, it is illegal for a minor to own a handgun, but the same law includes an exemption for target practice. The Crumbleys had sometimes gone to the range during the pandemic. A signed waiver for Ethan was already on file.

Ethan faced the long, narrow gallery first. He stepped slightly back from the small metal counter, lifted the pistol, and, turning it over, discovered how to click in the magazine. He aimed and fired, pausing and then, as he became accustomed to the motion, firing 14 times in quick succession. Jehn, behind him, waited for him to finish. The CCTV camera shows her jiggling her foot, which she frequently did later in court, in chains.

When Jehn took her turn, she approached the counter and Ethan showed her how to load the gun and flip the safety. After a couple of rounds, she called him over, and like a golf instructor, he rearranged the fingers of her left hand on the grip of the gun. She fired again, and when she was done, Ethan gently placed the pistol and the magazine back into the padded case. Then Jehn carried the case through the lobby and out to the parking lot. At around 7 p.m., Jehn posted a photo on Instagram. It showed a paper target riddled with holes. “Mom & son day testing out his new Xmas present. My first time shooting a 9mm I hit the bullseye.” She also posted a photo of the family’s Christmas tree, still untrimmed.

November 27, 2021: Ethan and Jehn at the gun range. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

Three days later, on Tuesday, November 30, while Jehn was at the office and James was out making DoorDash deliveries, Ethan, a sophomore at Oxford High School, went into the boys’ bathroom between classes. He allegedly took the SIG Sauer out of his backpack and walked down the long, curved hallway, shooting at his schoolmates. He has been charged as an adult in Michigan with the deaths of Madisyn Baldwin, Hana St. Juliana, Tate Myre, and Justin Shilling. The 24 felony counts against him include first-degree murder, assault with intent to murder, possession of a firearm, and terrorism. Michigan does not have a death penalty, and his trial will not begin until January at the earliest, but Ethan Crumbley can expect to spend his whole life incarcerated.

What took place at Oxford High School is a horror tale, agonizing in its particulars and familiar in its outlines. But then the Oakland County prosecutor, Karen McDonald, did something extraordinary. A former teacher and a mother of five, she stood up at a press conference three days after the shooting and, looking stricken but determined, announced she would be charging the shooter’s parents as well. James and Jennifer Crumbley face four counts each of involuntary manslaughter, charges that carry a maximum penalty of 15 years. In a prosecutor’s brief, McDonald wrote that criminal charges have never been brought against the parents of a school shooter before. But she was compelled, she said: “I am angry. I’m angry as a mother. I’m angry as the prosecutor. I’m angry as a person that lives in this county.” McDonald appeared incredulous that any parents could be so reckless as to buy a gun and tell their teenager — who was sad, isolated, and obsessed with firearms and violent video games — that it belonged to him.

Not everyone who works in the Oakland County prosecutor’s office thought McDonald was taking a prudent course. In general, prosecutors don’t accept cases they aren’t confident they can win. And McDonald, a popular Democrat in a politically mixed county, would have known she was entering a morass. Oxford is gun country, and no one in town wanted to frame the shooting as a gun problem. In Oxford, kindergartners get BB guns as gifts, and high-schoolers post selfies with their guns and hunting trophies on Instagram. Elissa Slotkin, the Democratic congresswoman from the district, spent childhood summers on a farm nearby, where her father kept more than a dozen guns in his office, all unlocked. Since the shooting, it’s not uncommon to see a pickup truck bearing two bumper stickers: one with an assault rifle and a 2A slogan, the other with OXFORD STRONG, the post-shooting mantra of the town.

The Crumbleys owned three handguns, including the new pistol, and in a letter she wrote to Donald Trump congratulating him on his win in 2016, Jehn thanked him for supporting her right to bear arms. Michigan is an open-carry state, and concealed-carry permits are easy to obtain. (The Accurate Range offers certification courses on Saturdays and Sundays.) There are no safe-storage laws in Michigan, meaning that even if the Crumbleys did have the SIG Sauer unlocked on the night before the shooting, they wouldn’t have been committing a crime. McDonald regards the gun laws in Michigan as “woefully inadequate,” as she said at the press conference, but she didn’t press the point.

Instead, McDonald declared she would prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Jennifer and James Crumbley had grossly neglected their parental duty by not averting the obvious danger their son presented — and so were directly responsible for the deaths of four teenagers, the injuries of seven, and the trauma of the town. The parents’ trial is scheduled to begin on October 24, and based on preliminary court filings, the evidence before the jury will be a catalogue of an American family’s everyday life: text threads about chores, vacations, whereabouts, and homework; selfies, cell-phone videos, and social-media posts; school communications and unpaid bills; phone records and voice-mails. McDonald will say all the evidence adds up to a picture of parents so inattentive and irresponsible that they failed to heed Ethan’s cries for help and instead gave him a gun. Shannon Smith and Mariell Lehman, the lawyers for Jennifer and James, respectively, will say that the Crumbleys may not be perfect people but that there’s no legal mechanism to convict them of a crime based on what they didn’t know about their son. The outcome will depend on a jury’s determination of where these parents’ responsibilities end and how much they should have been expected to see.

November 27, 2021: Ethan and Jehn testing out the new sig Sauer 9-mm. pistol. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

After the shooting, James and Jennifer went to the local police station, where they were interviewed. James started making calls to lawyers; Jehn begged her boss to let her keep her job. “I’m bawling right now,” Jehn texted a friend that night. “My son ruined so many lives today.” Then they fled their home on East Street — now a crime scene — for a hotel. The Crumbleys did not feel safe, their lawyers said later, with the press camped out and death threats swamping their phones. Upon learning that they were also to be charged, they holed up in an artist’s studio in a Detroit warehouse belonging to one of Jehn’s acquaintances and stopped responding to phone calls. At around 1:30 a.m. on the Saturday after the press conference, police found them there. Prosecutors say they had four burner phones (one they’d tried to destroy), four gift cards, ten credit cards, and $6,600 in cash. They had cleaned out Ethan’s bank account. According to a prosecutor’s motion, Jehn told a friend that “her son’s destiny is done and she has to take care of herself.”

Over two days in February, a preliminary examination was conducted at the Oakland County courthouse to establish the prosecutor’s right to move forward with the criminal trial. (The reporting in this story includes public testimony and documentation from those hearings, as well as other court filings and testimony. On June 27, Judge Cheryl Matthews issued a gag order preventing attorneys on both sides from speaking to the press. Neither the prosecution nor the defense were able to comment.) In Oxford, residents closely followed these proceedings and every motion and court appearance since. It’s a small town, nearly everyone I spoke to knows at least one of the victims or their family, and the fury directed at the Crumbleys is palpable. “I blame the parents completely,” Rosemary Bayer, the Democratic state senator from the district, told me. “I’m not a doctor. I’m not a psychologist. But it’s never the kid’s fault.” Twice, the Crumbleys’ lawyers have asked the court to reduce their bond from $500,000 to $100,000, and twice they’ve been denied. Marisa Prince, who serves lunch at Oxford schools and employed Hana St. Juliana as her children’s babysitter, believes the Crumbleys are better off in jail. “They’re safer there,” she says. “People are on edge with how mad they are.”

A special antipathy is reserved for Jehn. In town, people speak of her as not maternal, “a ballbuster,” absent at home. On private Facebook pages, Jehn is depicted as “the one pulling the strings, wearing the pants, the mean one,” says Lori Bourgeau, who is on the Oxford Village council. In the public mind, which extends far beyond Oxford, James is seen as the passive, gentle parent and Jehn as a mother who failed to support her son with love or discipline and who, when things started to go wrong, remained blind to her child’s descent. The lawyers for James and Jehn used to be partners, and the question of a conflict of interest has come up repeatedly in court. Buried within that question is another: whether James might testify against his wife and take a plea.

November 27, 2021: Jehn’s Instagram post of the new gun. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

Oxford is a town of 22,000 people, wedged between horse farms to the north and Detroit and its suburbs to the south. Politically speaking, Oxford is pure purple; since the 1990s, it has voted for George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Mitt Romney, then Trump twice — the last time in a squeaker. Oxford High School, the only one in town, is the magnetic force at the center of it all. The social lives of adults and children revolve around the schedules of the varsity sports teams, and during football season, the whole town pours into the school’s stadium, where the field is covered with professional-grade blue turf, an extravagance that required some members of the Wildcats booster club to put up their homes for collateral in case the town couldn’t pay the tab.

Jehn grew up in Clarkston, 14 miles away. In high school, she skied with the junior-varsity team; in her 1996 senior yearbook photo, her face is framed by a bouffant. She had a brash, sarcastic side, as she said in her letter to Trump, which was downloaded from James’s Facebook page and circulated widely after the shooting. That’s why, even though she regarded herself as a feminist, she didn’t mind Trump’s “grab ’em by the pussy” comment: “I say things all the time that people take the wrong way, do I mean them, not always.”

She and James married on the beach in Florida in September 2005. Two years older and tall, tanned, and hazel-eyed, James had grown up around Jacksonville. He was charming — “happy-go-lucky,” according to people who know him, the kind of guy who’s always asking you over for a beer. Florida public records show that James was brought to court for passing bad checks and driving with a suspended license. Jehn, too, has been charged with writing bad checks. They were both found guilty in a 2005 DUI.

Ethan was born in 2006, and when he was in elementary school, the Crumbleys moved to Oxford. Their house was not the best house on East Street but not the worst one, either. It was one story with three bedrooms, a sunny kitchen, a carport, and a shed out back. Over time, the Crumbleys adopted a menagerie: Tank, a Great Pyrenees; Harley, a wolfish white rescue dog; Stella, Jehn’s cat; and Dexter, Ethan’s cat. For a while, Ethan kept a chinchilla, too.

The Crumbleys were different from most of the other families on East Street in a way that sometimes raised eyebrows. In the summer, they liked to light firecrackers in their yard, even though the noise terrified Tank so much that he would run down to a neighbor’s house to hide there. James was around the house a lot, often grilling out by the carport. He was “superfriendly. He was always high,” this neighbor says. (Police say that photos taken of the house after November 30 show evidence of marijuana having been grown in the cellar.) Jehn, the neighbor said, was almost never home. Upon resettling in Michigan, she had gotten her real-estate license and then a job as the social-media assistant at a real-estate company in Bloomfield Township. Over the next five years, while James cycled through gigs, Jehn became the family’s main earner, working her way up to marketing director. She was good at her job, “professional,” her boss testified at the preliminary examination.

From left: December 3, 2021: The Crumbley house. Photo: JEFF KOWALSKY/AFP via Getty ImagesNovember 30, 2021: A police photo of Ethan’s room. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

The Crumbleys were not part of the OHS social life; no one could recall ever seeing any of them at a football game. “These people didn’t do that,” says Mike Aldred, a father of one of the players who was a friend of Tate Myre’s. “No one would notice the family if they dropped into a restaurant because they weren’t connected to the community.” Instead, Jehn took riding lessons at the horse farms in the countryside near Oxford and eventually bought two horses — first Shorty, then Billy. She also made friends as a volunteer on the ski patrol at Pine Knob, the tiny resort where she had skied as a kid, and on Wednesday nights, she and James played euchre at a brewpub in town. On weekends, the Crumbleys occasionally went camping, their kayaks strapped to the roof of their car.

Still, their lives in Oxford seemed to be teetering. James had two children back in Florida, and he and Jehn were often embroiled in long-distance combat over child support with the mother of his other son. When they went on weekend trips, Jehn would sometimes ask the neighbor to care for their pets; the neighbor says she would find their house in a mess: garbage stacked up against the side of the shed, the bedrooms the way “I would imagine a frat house at the end of the semester.” The interior had a stench. “The dogs would piddle on the floor in the same spot,” the neighbor says, but “Jehn laughed it off.”

Ethan mostly kept to himself, but when this neighbor passed him on the street, he always looked her in the eye and gave her a friendly wave. Not many people seemed to know him at school; those who did called him quiet and “relatively nice,” said Madeline Johnson, who was Madisyn Baldwin’s best friend.

March 17, 2021: Jehn with one of her horses. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

By the early months of 2021, family life on East Street had grown tense. During the 2020–21 school year, classrooms were open, but the schedule was unpredictable: Kids and teachers were frequently out sick. Seven weeks of school that year were virtual, a reality Ethan found “incredibly difficult,” according to his guidance counselor’s court testimony. He was spending a lot of time alone in his room.

During the pandemic, James had lost a telemarketing job and begun driving for DoorDash. The couple were behind on house payments. Jehn and James would fight in the backyard, yelling so loudly that passersby could hear. Later, in court, a co-worker said Jehn’s phone arguments with James were audible through her closed office door.

James was often home with Ethan, and during the day, Jehn would frequently check in with them, asking about homework, meals, and chores. “I think your dad is sleeping,” Jehn wrote to Ethan at lunchtime on March 6.

It was around then, a little before his 15th birthday, that Ethan started to send his mother a series of texts that will be produced as evidence at trial. In the texts, Ethan said he was hearing things. Imaginary presences felt real to him. He sounded lonely and afraid. “Can you get home now?” he wrote on March 9. “There is someone in the house I think. Someone walked into the bathroom and flushed the toilet and left the light on. And I thought it was you but when I came out no one was home. There is no one in the house tho. Dude my door just slammed. Maybe it’s just my perinoa [sic]. But when are you going to get home.”

March 9, 2021: A text from Ethan to his mother describing what appear to be hallucinations. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

About a week later, he seemed to be hallucinating. “Ok the house is now haunted,” he wrote. “Some weird shit just happened and now I’m scared.” And then: “I got some videos. And a picture of the demon. It is throwing BOWLS. I am not joking it fucked up the kitchen. I am just going to be outside for a while.” And finally, “can you at least text back?” If Jehn responded to him either of these times, she did not do so by text or phone.

The next day, Ethan had a meltdown. He was “really worked up and out of control,” Jehn texted James later. She gave him something to help him sleep — either melatonin or Xanax — and he fell asleep in his parents’ bed, waking up with a headache and wondering why he wasn’t in his own room.

Jehn texted James the next morning.

“You awake? Ethan awake?” she wrote just after 9:30 a.m.

“Um yeah,” he wrote. They went back and forth before Jehn decided what to do. Ethan needed to eat, work hard, and not complain, she said. On the thread, James is silent, so Jehn prods him again. “You respond and I didn’t get it?” Jehn writes.

“Jesus,” James responds.

At the preliminary examination in February, McDonald introduced the texts from Ethan to Jehn to show that the mother knew of her son’s distress yet did not take him to a doctor. Jehn had health insurance through her work, but neither James nor Ethan was on her plan. Jehn’s attorney, Shannon Smith, pointed out that it’s hard to know what a handful of texts among thousands means.

Ethan had one close friend, and in the spring of 2021, he started telling the friend by text how awful he felt. He got 17 hours of sleep over five days, he said. He was laughing and crying in the shower. He had tried to talk to his parents, but they wouldn’t listen, Ethan said.

On April 5, Ethan told his friend by text that he was thinking about calling 911 on himself but was afraid his parents would be “really pissed.” He thought he was having a mental breakdown.

“I am going to ask my parents to go to the doctor’s tomorrow or Tuesday again,” Ethan wrote. When he tried to talk to his parents before, his father had given him some medicine and told him to “suck it up,” and his mother laughed. “She makes everyone feel like shit,” he wrote.

“But this time I am going to tell them about the voices. I only told them about the people I saw.”

“Ok,” the friend wrote back.

“I also have a weird rash growing on my chest. It’s not COVID cause I got a test.”

“Hopefully they can help you man,” the friend wrote.

“Like I am mentally and physically dying,” wrote Ethan.

McDonald, the county prosecutor, is building her manslaughter case by showing that the Crumbleys failed to exercise what in the law is known as “ordinary care.” Also known as “reasonable” or “due” care, ordinary care is usually applied in civil lawsuits to prove negligence, as when a supermarket owner fails to shovel the icy walk in front of the store and is held liable when a customer slips and breaks a leg. The law understands that an ordinary person would take care to shovel the icy walks to avert such foreseeable incidents, so the negligent supermarket owner must pay a court-ordered fine. Negligence is not, generally speaking, a crime.

Occasionally, though, a prosecutor will use “gross negligence” to support a homicide charge, as when a doctor prescribes a drug to which they know a patient is allergic, or a driver texts and speeds, or a parent leaves a baby locked in a hot parked car. In these cases, a prosecutor will use words like wanton and — as McDonald does frequently — egregious to indicate an extraordinary, criminal level of negligence. Manslaughter is murder without intent or malice.

April 5, 2021: A text exchange between Ethan and his friend. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

McDonald once said she “instinctually knew” she would prosecute the Crumbleys, and she has since turned herself into a fierce ally of the families of the victims. She has made the case her priority; according to Lori Borgeau, in one conversation, McDonald said “she doesn’t really care where her future goes, politically.” In Oxford, support for her is nearly universal. The topic of gun restrictions is divisive, but even loyal gun owners can get behind the notion that the abandonment of personal responsibility should be punished. “Speaking as a Michigander and lifelong gun owner, responsible gun ownership requires the mental awareness to lock and secure your firearms,” says Mike Aldred. In the case of the Crumbleys, the gun “wasn’t secured. There wasn’t a care in the world. We’ve lost four babies because of it.”

Gross negligence is not a subjective charge, and a jury can’t convict the Crumbleys because it finds them abhorrent or insufficiently parental. To convict someone of manslaughter through gross negligence, a prosecutor in Michigan must prove that the defendant knew of a potentially dangerous situation, that they could have averted harm through ordinary care, and that the disastrous harm to others presented by the circumstances would have been apparent to an ordinary mind — what the attorneys call “foreseeability.”

McDonald is relying on limited precedent. In Oakland County, children regularly die of gunshots owing to the carelessness of their parents, according to Bayer, the state senator, and those parents are almost never charged with crimes. But there are exceptions, notably the 2016 case of People v. Head, in which a Detroit man left a loaded shotgun in the closet of a bedroom where his two kids decided to act out a violent video game, resulting in the death of his 9-year-old son. Head was found guilty because he knew the gun was within reach of his unsupervised children, he could have easily intervened by separating the ammunition from the gun or preventing them from accessing it, and any ordinary person could foresee that children playing with a loaded gun could result in grievous harm. The verdict was upheld on appeal.

In the Crumbley case, this kind of direct effect is more difficult to establish. The shooting was no accident, and the shooter was not a young child but an adolescent, capable of deceiving his parents. And to prove foreseeability, McDonald has to show that the Crumbleys, had they exercised “ordinary care,” would have discerned that their son could endanger lives. This is challenging, says Eve Primus, a professor at the University of Michigan School of Law. “Lots of parents have children who are troubled at various points,” she says. “What is the line where you should know that something like this would happen? What is the line between not-great parenting and criminal?”

James and Jennifer each face the same charges, but at the preliminary exam in February, McDonald emphasized Jehn’s role. In particular, she focused on the care and attention Jehn paid to her horses as proof that she prioritized her own pleasure to the detriment of her son and the safety of the community. McDonald showed that, during the months that Ethan was spiraling, Jehn went to the horse barn after work several days a week. James frequently came along while Ethan stayed home, testified Kira Pennock, who owns the barn where the Crumbleys boarded their horses and was friendly with them. Jehn knew that Ethan was “weird,” Pennock said, and that “he wasn’t out doing things like a normal kid.” Jehn had told her that “he only had one friend and that he spent a lot of time online or playing games, but he just seemed to keep to himself.”

To amplify the portrait of Jehn’s selfishness, McDonald showed that, in the year leading up to the shooting, Jehn had romantic distractions as well. Sometime in the spring or summer of 2021, Jehn and James had agreed to separate, though neither moved out of their East Street home. Jehn confided in her co-worker Amanda Holland that she had met a man whom she would see during the day, telling colleagues she was out doing errands.

“She said this person would pick her up and they would go across the street from our office,” Holland said in court.

“To where?” McDonald asked.

“Costco,” Holland replied.

“And did she say what they were doing?”

“Not directly, no.”

In the courtroom, Smith, Jehn’s lawyer, swiftly objected to this testimony, citing relevance (she was overruled), and in subsequent motions and court appearances, she and Lehman, James’s lawyer, have tried to divert the court’s attention from the character of the Crumbleys and toward what they knew and what they did. In May, Smith and Lehman submitted a long list of evidence they wished to exclude from the upcoming trial: the marijuana growing in the basement, the numerous half-empty alcohol bottles discovered after the shooting, the messiness of the house, the marital issues, the horses. Alcohol and marijuana are legal in Michigan, the defense argued, and evidence of a messy house “would place the Crumbleys on trial for not being as neat and tidy as some may believe that they should be.” Similarly, Jehn’s alleged affair would prejudice the jury against her unfairly, they argued. And just because Jehn cared for her horses doesn’t mean she didn’t care for her son, they said. The judge acceded to many of the defense’s requests, with several key exceptions. One was the horses. McDonald showed that, during the very hours Ethan was having his two apparently hallucinatory episodes and asking his mother to reply, Jehn was at the barn, taking selfies and photos of her horses. Her lawyer said that cell reception can be spotty there.

In the late spring of 2021, Ethan was torturing and decapitating baby birds. He allegedly did this in secret when his parents weren’t home, making long, grotesque videos with his phone. For at least five months, Ethan kept a bird’s head in a jar in his room, under a sheet.

“Holy shit,” he texted his friend on October 11, “my mom legit almost found the bird head. She pulled away the sheet covering it and it was fully exposed but IDK how the fuck she didn’t see it.” Several weeks before the shooting, he brought the jar to school and left it in a bathroom.

One night in August, Ethan made a video of himself handling his father’s .22-caliber KelTec pistol and sent it to his friend with an invitation to go to the shooting range the following Sunday. The friend apologized and said he wasn’t able to ask his parents. “No hard feelings,” Ethan said. Then, at 12:30 a.m., Ethan sent another video, this time of himself loading the gun and pulling back the safety. The pulse of late-summer crickets is audible, and a cat is sleeping nearby.

“Niiice,” the friend texted. “Now pull the trigger, Jkjkjkjk.”

“My dad left it out, so I thought, ‘why not?’ lol,” Ethan replied. He knows gun safety, he added, so “it’s no problem.” This was met with silence, and Ethan texts again. “Now it’s time to shoot up the school, JKJKJKJKJK.”

August 20, 2021: Ethan’s text to his friend describing playing with his dad’s gun. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

That fall, Jehn and James had reconciled. According to their lawyers, neither of them knew anything about these texts. But Jehn told friends that she was worried about Ethan, according to interviews and court testimony. His grandmother in Florida had died earlier that year and then Tank, one of the family dogs, had died. Ethan was taking the losses hard.

Around Halloween, Ethan’s friend was admitted to a treatment facility and the correspondence between them ceased. Ethan began spending hours on a website devoted to killings and school shootings. During the month of November, he went to the website 421 times. He also kept a journal, 21 pages of writing and drawing in a black notebook. “I have fully mentally lost it after years of fighting with my dark side,” Ethan wrote. “My parents won’t listen to me about help or a therapist.” His father knew about the journal and encouraged him to express his feelings in it. But according to the Crumbleys’ lawyers, neither parent ever looked at it, nor did they check his phone for videos, photos, or text messages or look at his browser history.

The legal dispute between the defense and the prosecution boils down to this: Should the Crumbleys be judged for what they knew, or for what they should have known? At trial, Smith and Lehman will likely argue that a jury can’t convict the Crumbleys for not having information that their son was going to murder classmates at school. And McDonald will say that any other parents would have known and intervened. Ethan had three Instagram accounts, and his parents followed one of them, but it seems not to have aroused their concern. He was posting images of deformed faces, with protruding jaws or blank eyes, contorted with glee.

Aug. 20, 2021: A video still of Ethan playing with one of the other guns in the house. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

Sue Klebold believes she was a good mother. She knew all of her son Dylan’s friends. She did not allow guns in the house. She prided herself on being the type of mother who “got up in the middle of the night to talk to him when he came home from the prom.” On April 20, 1999, Dylan Klebold and his friend Eric Harris murdered 12 classmates and one teacher at Columbine High School before killing themselves. In 2016, Klebold published A Mother’s Reckoning, in which she describes her experiences living with Dylan during the last years of his life: his withdrawal, his irritation in the company of others, his annoyance at being asked to feed the cats, a meeting with his English teacher over a disturbing school paper. None of these things was sufficiently alarming on its own to propel her to act differently.

According to Klebold, all parents invest deeply in the illusion that their kids are “fine.” When they’re forced to consider that may not be true, an intellectual revolt occurs. In a 2015 report called “Making Prevention a Reality: Identifying, Assessing, and Managing the Threat of Targeted Attacks,” the FBI demonstrates that parents are among the least proactive identifiers of potential violent mass killers. Suspicious of interventions from outsiders and anxious about disapproval or punishment, parents fail to see red flags or minimize them. “As parents, we can’t know everything our children are thinking and planning. If someone is determined to hurt someone, they will hide it from us,” Klebold told me. The Sandy Hook shooter murdered his mother in her bed before going on to kill 26 people at Sandy Hook Elementary School. “She slept with her bedroom door unlocked, and she kept guns in the house, which she would not have done if she were frightened,” her ex-husband once said. Among kids who have thoughts of suicide, 50 percent of their parents have no idea.

Parenthood is the most ordinary of human occupations, but the idea of an “ordinary family” is artifice, an ad hoc collection of societal norms. From birth, a child is meeting or not meeting standards — height, weight, fever lines on a graph, with dire or possibly not dire consequences — and it goes on from there: grades, friends, mood changes, body changes. Sometimes a kid is just underweight, and sometimes he needs to see a doctor. Sometimes a bad fight is just a bad fight, and sometimes it’s a precipitating event. As Klebold points out, not even good-enough parents can always see their children clearly.

In Oxford, countless people I spoke to framed the events leading up to November 30 as “a mental-health story”: kids falling apart in a desert of care, the same as everywhere else in the country, but in some ways worse. Even before the pandemic, administrators in Oxford schools had started to notice more fragility, anxiety, depression, and withdrawal among students. In the late 1990s, the Republican governor John Engler had closed three-quarters of Michigan’s psychiatric hospitals in a cost-cutting spree, leaving rural areas barren of psychiatric inpatient treatment for kids. There was some outpatient help available, but many families didn’t know where to find it “unless they were very savvy,” one administrator told me. When they did, wait times averaged four months. This backlog strained emergency rooms. “Every time a kid said, ‘If I don’t get an A on this spelling test, I’m going to kill myself or kill you’ or something,” she was sent to the ER, says Sheila Marcus, a psychiatrist at the University of Michigan who runs a program that trains primary-care doctors in mental health. Ninety percent of the time, these kids were deemed “not a threat” and sent back to school.

At school, mental-health support was far from robust. Shawn Hopkins, Ethan’s guidance counselor, testified in court that he was one of four counselors at the high school looking after the needs of 1,800 kids. This gave him time to see each student for ten minutes once a year, barring crises. He was performing one or two suicide-risk assessments each month. Meanwhile, among certain parents, a mistrust of educators, institutions, and authority figures was growing — a stubborn sense of “You’re not going to tell me what to do with my kid,” as Rosemary Bayer put it.

During the pandemic, suicidality among kids in Michigan rose substantially, according to Marcus, and doctors were feeling panicked. They’d call her and say, “I have many patients who have guns in their home, who are depressed, who may be suicidal.” At OHS, guidance counselors were getting regularly pulled away to cover classrooms when teachers were sick, Hopkins testified. It was often impossible for teachers to assess kids’ well-being over Zoom. “We had eyes on the kids,” said Anita Qonja-Collins, the assistant superintendent of elementary instruction in Oxford, “but did we really have eyes on the kids?”

November 26, 2021: The sales receipt for the SIG Sauer, purchased by James. Photo: submitted in evidence from Michigan

The Friday after Thanksgiving, James went down the road from East Street to Acme Shooting Goods and purchased the 9-mm. for $519.35 using his credit card. Ethan came along and waited while his father ticked a box attesting that he understood it was illegal to buy a gun for someone else and signed a form acknowledging that his new gun came with a safety lock.

The following Monday in English class, Ethan was looking at bullets on his phone. The teacher, alarmed, notified Pam Fine, the high school’s “restorative-practices coordinator,” and Fine called Ethan to her office for a meeting with herself and Hopkins. He didn’t know Ethan very well: They had met once over Zoom for scheduling and once in a hallway after a teacher said Ethan seemed “sad.”

After the meeting with Ethan, Fine left a message on Jehn’s phone. She let her know that she and Hopkins had just had a “really nice” conversation with Ethan, assuring him that “guns are a hobby for a lot of people, and shooting ranges, and that’s perfectly normal,” but that certain hobbies were better pursued at home. “He was great; he was like, ‘Yep, I get it,’ ” Fine said, her voice upbeat. “If you have any questions, you can give me a call. Otherwise, I hope you have a great holiday.”

Jehn texted Ethan, “Seriously?? Looking up bullets in school??”

“What? Oh yah. I already went to the office for that,” Ethan replied. “Completely harmless. Teachers just have no privacy. They said I’m all good. This is nothing I should get in trouble about.”

“You’re not. They left me a voicemail.” And then, a wisecrack: “Did you at least show them a pic of your new gun?”

“No I didn’t show them the pic my god.” Ethan reiterated that it was harmless. “I guess the teachers can’t get their eyes off my screen smh.”

Jehn wrote, “Lol, I’m not mad you have to learn not to get caught.” She assured Ethan that he could listen to the voice-mail when he got home.

After school, Ethan and his parents had a terrible argument. In his journal, Ethan wrote, “The shooting is tomorrow, I have access to the gun and ammo.” He also addressed his parents: “I love you, Mom. I love you, Dad. I’m sorry for never saying it back.”

Previously, he had written in his journal about how he wanted a 9-mm. to “maximize the number of kills” and how he was “enlisting his own father” to get it for him, the prosecution said in a hearing for Ethan’s trial. After obtaining the gun, Ethan posted a photo of it on Instagram, calling the SIG Sauer “my new beauty.” Sometime that weekend, he also wrote in his journal, “I will have to find where my dad hid my 9-mm. before I can shoot the school.” In the early hours of Monday morning, at around 3 a.m., Jehn was on her phone, searching “research clinical depression treatment options.”

November 30 was a Tuesday, and it looked like snow. Jehn went to work, Ethan to school. The Crumbleys’ horse Billy had a fungus called mud fever, so James drove to the barn to put ointment on its legs. Jehn had plans to look at a property with colleagues and then go to the barn.

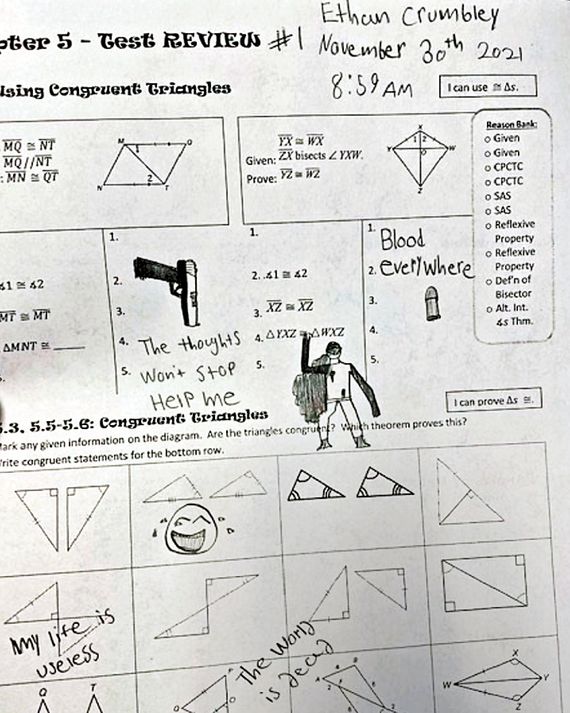

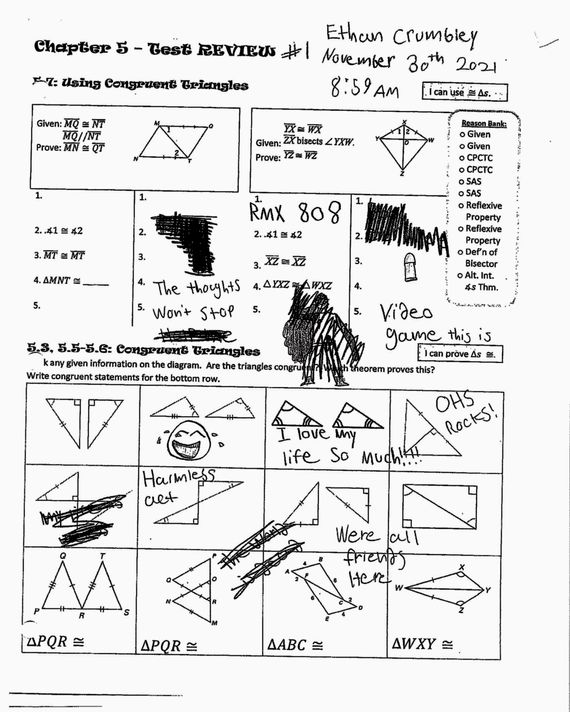

At 9:33 a.m., she texted James, “Call NOW. Emergency.” She texted again: “Emergency.” At 9:38, Jehn texted two photos of a math sheet Ethan had been working on that morning. During second period, the geometry teacher had walked past Ethan’s desk, and what she saw caused her such alarm that she took a photo with her phone and brought it to Nicholas Ejak, the dean of students. On his review of congruent triangles, Ethan had drawn a pistol almost exactly like the one his father had just bought. He had drawn a human figure filled with holes and a laughing-crying face. He had written, “The thoughts won’t stop. Help me.” And “Blood everywhere.” And “The world is dead.” By the time Hopkins arrived to pull him out of class, Ethan had scribbled out the gun, the bullet-riddled figure, and the dark phrases. He had written, “OHS Rocks!” And “I love my life so much!!!!” And “We’re all friends here.” And “Harmless act.”

“My god, WTF,” James texted Jehn when he saw the pictures.

“I’m very concerned,” Jehn wrote. She asked him to call her because she was headed to the school.

As Jehn drove, Hopkins and Ethan were having a talk. The geometry teacher wasn’t the only one who raised the alarm that morning. In first-period English, Ethan had been watching shootings on his phone; that teacher had alerted Hopkins as well. In court, Hopkins reported Ethan was compliant and understanding at first, but when asked to talk about drawings on the math sheet, Ethan grew “sad”: “He talked about how a family dog had died. He talked about how he had lost a grandparent, that COVID had been incredibly difficult for him.” Ethan mentioned his friend who wasn’t in school anymore and an argument he’d had the previous night with his parents. Hopkins did a standard suicide-risk assessment, he said. He asked Ethan whether he was a threat to himself or others.

Ethan reassured Hopkins. “I can see why this looks bad,” he responded, according to Hopkins. “I’m not going to do anything.”

In English, he was watching video games, Ethan explained. He hoped to be a video-game designer one day, and the pictures he drew on the math sheet were sketches for a video game. Nevertheless, Hopkins had decided to contact the parents, as “there was enough suicidal ideation to be concerned,” he said later in court. Still, “I did not ask him further questions about a plan.”

James and Jehn arrived together at the high school at about 10:30 and were guided into Hopkins’s office. Hopkins explained that he was worried about suicidality and gave them a list of local mental-health resources. James looked at the math sheet with Ethan, telling him he had them to talk to if he was upset and his journal to write in. Hopkins declared he wanted Ethan seen by a mental-health professional — today, if possible, he said. That’s when Jehn said “no,” according to Hopkins. “Today is not possible. We have to return to work,” she said. So Hopkins said he wanted Ethan seen within 48 hours, and he would be following up. The meeting ended “abruptly,” Hopkins said.

Everyone in Oxford would like to know exactly what went on in that meeting, for when all is said and done, the apportioning of blame and guilt can be found in those 15 minutes. In the preliminary exam, Hopkins said he had never seen parents so recalcitrant when informed that their child might be considering suicide. He felt, he said, that James hadn’t spoken up because he didn’t want to contradict Jehn. During cross-examination, Smith reminded Hopkins of his role as mandatory reporter. If he had felt Ethan were truly in danger, from himself or his parents, Hopkins would have been obligated to call CPS or 911 right away. He did not, nor did he or Ejak insist that Ethan be sent home. Over the subsequent months, nine civil lawsuits would be filed against the school. (The Oxford Community School District did not respond to requests for comment for this article.)

Ejak had joined the meeting partway through, and it was he who determined there was no “discipline issue.” Had the school decided that Ethan had broken any rules, the meeting might have taken a different course — actions that could have included a suspension from school or a search of Ethan’s backpack. Instead, Ejak went to the geometry classroom, retrieved the backpack, and gave it to Ethan, who said he wanted to continue his day. Hopkins agreed, saying in court that he was worried above all for Ethan’s own safety and did not want him to be alone.

After the meeting with Hopkins, Jehn was revising her plans. She still wanted to come to the barn, she texted Pennock, but now she would be bringing Ethan along. Ethan “can’t be left alone,” and James was working that evening. Pennock lightly suggested Ethan might benefit from “horse therapy.”

“Let’s make him a cowboy,” Pennock texted.

“Lol mom goals for real!” Jehn replied.

Back at work, she ran into her boss in the copy room and told him she needed to find a therapist for Ethan. She passed by Amanda Holland’s desk, showed her the math sheet, and said she felt like a failure as a parent.

At 12:20, she texted Ethan. “You ok?”

“Yah I just got back from lunch.”

“You know you can talk to us and we won’t judge,” Jehn wrote.

“Ik. thank you. I’m sorry for that. I love you.” It was 12:42.

Although the parents of mass shooters are almost never charged with crimes, victims’ families frequently sue the parents for damages. Thirty-six lawsuits filed by the Columbine families named Sue Klebold and her ex-husband, Tom, as defendants. The families of 16 of the victims of the Sandy Hook shooting sued the estate of the shooter’s mother. One of the Parkland survivors sued the shooter’s foster parents, saying they knew their foster son had guns but did not stop him from accessing them, as well as the estate of his deceased mother, saying she had failed to attend to his mental-health issues. These lawsuits are agonizing for the families of the victims, their loved ones reduced to payout sums, and they rarely have a deterrent effect.

Could a criminal case succeed in preventing future shootings in a way that these civil cases have not? The father of the Highland Park shooter, from July 2022, sponsored his son for a gun permit despite a suicide attempt and homicidal threats. The Buffalo shooter, from May 2022, worried online that his parents would find the guns he hid at home. The Uvalde shooter, from that same month, who lived with his grandparents, bought two assault rifles days after his 18th birthday. According to the Violence Project, the average age of a school shooter is 18, in legal terms an adult. Mass shooters tend to be older. To criminally prosecute the parents of an adult shooter, the state would have to show, say, evidence of aiding and abetting or conspiracy. In the 2018 Waffle House murders, the father of the 29-year-old shooter was convicted of unlawful delivery of a firearm.

In the U.S., the urgent desire to stop mass shootings — and gun violence in general — is met with almost total refusal in conservative state legislatures to pass laws or restrictions that make careless gun ownership a crime. “I don’t think there’s anything on the horizon that’s very encouraging,” says Allison Anderman, director of local policy at the Giffords Law Center. Meanwhile, 4.6 million children live in homes where loaded firearms are unlocked; a 2021 survey showed that 70 percent of parents believe they have sufficiently secured their weapons, while a third of their adolescent kids say they can find them within five minutes. In 2020, 4,368 kids died of gunshot wounds in America, making it the leading cause of childhood death. A third of these were suicides.

Nineteen states and the District of Columbia have passed Child Access Prevention laws that impose criminal penalties on people for inadequately guarding their guns from children. Some are very stringent, as in California, where it is illegal to negligently store a firearm that a child might access, even unloaded. Some are less so: In Illinois, criminal responsibility of the parent is invoked only if the child uses the weapon to kill or seriously hurt someone. A consortium at the University of Michigan found that when CAP laws are paired with felony enforcement, gun deaths among kids younger than 15 decrease by a quarter, but nationwide, most of these laws are decades old and lately pass only when a state legislature turns blue. After the Oxford shooting, Bayer introduced a CAP bill in the Michigan legislature for the third time, but it has little to no chance.

To prove gross negligence, McDonald is attempting to draw a causal chain between the Crumbleys’ behavior and the deaths of four teenagers, but one element interrupts it, and that is Ethan himself. McDonald has charged him as an adult. He resides in an adult jail and faces adult penalties. In a February hearing related to Ethan’s trial, prosecutors painted him as highly intelligent, calculating, and deceitful. “In public, you have to put on a mask to blend in,” Ethan once wrote to his friend. (According to court documents, he may be planning an insanity defense.)

The parents and child face different trials and consequences, but their narratives overlap. Can McDonald prove both that the shooter is adultlike, and thereby responsible for four counts of first-degree murder, and that his parents are directly responsible? The case of the Crumbley parents will be decided on the interpretive fine points. Did James and Jehn outright buy their minor son a gun, as the prosecution attests? Or did they “give” him a gun, in the sense that other parents might give a child a car or a precious piece of jewelry under stipulations of technical parental ownership and control? Does the responsibility for Ethan’s possession of the gun that day rest on his parents for failing to secure the gun or on him for taking it?

If McDonald wins, it will be in part because of the community’s yearning for “a pound of flesh,” as University of Michigan Law School professor Frank Vandervort puts it. But legal precedent is a way of articulating community standards, and Vandervort worries about a conviction eroding a fundamental principle of the law: “I’m responsible for what I do, and I’m not responsible for what you do.” It’s one thing to hold an adult criminally responsible for the actions of a young child, but it’s another thing to shift criminal responsibility onto the parents of a teenager. “In some sense, for every teenager who commits a crime, you can point the finger at the parent,” Vandervort says. “You didn’t get therapy. You didn’t see the behavioral problems. What if your teenager takes your car, drinks, and kills someone? Are you going to be held responsible? Every parent who looks at this case must in some way say, ‘There but for the grace of God go I.’ ”

Primus, the University of Michigan Law School professor, also points out that, as gun possession becomes more criminalized, arrests and punishments will land disproportionately on Black and brown parents. She notes that Christopher Head, the defendant in the precedent-setting gross-negligence gun case in Michigan, is Black. “What happened at that school is awful. Obviously, Ethan Crumbley has to answer for that,” Primus says. “But I worry about the expanding criminal footprint.”

James, driving for DoorDash on Route 24, saw police cars streaming toward the school and rushed home to look for the gun. It was just after one. He called Ethan, who didn’t pick up. He called Jehn. From ten feet down the hall, her boss heard Jehn scream. “I saw her, Mrs. Crumbley, say there was an active shooter at her child’s school and she had to go,” Andrew Smith said in court.

Between 1:17 and 1:18, James called Ethan three more times. At the same time, Jehn was texting their son. “I love you too,” she wrote, in response to Ethan’s previous message. Then, “You ok?”

At 1:22, she sent him another text: “Ethan don’t do it.”

About ten minutes later, James, from East Street, called 911, his voice strained and frantic. “I have a missing gun at my house,” he said. He tried to explain about the counselor and the math sheet, how he was driving and heard about an active-shooter situation at the school. “I raced home just to, like, find out, and I think my son took the gun. I don’t know if it’s him. I don’t know what’s going on. I’m, like, really freaking out.” The Crumbleys say they feared suicide; McDonald says they must have been imagining homicide: Hundreds of parents rushed to the Meijer supermarket to pick up their kids that day, and afterward, McDonald would note the Crumbleys were the only ones who went home to look for their gun. Sue Klebold says sometimes the impulses for suicide and homicide are interwoven. A child throws his own life away by inflicting his suffering on others.

Hana St. Juliana was 14 years old. She was joyful, with a sarcastic sense of humor, a volleyball and basketball player, and close with her family, especially her older sister. She loved Christmas and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Madisyn Baldwin was 17. She loved Monster drinks and was smart and shy and an incredible artist. She doodled on everything, including gum wrappers, and had already been accepted to several colleges on full scholarship. Tate Myre, No. 42 on the football team, was a leader; even adults quieted when he spoke. “You had no choice but to follow him and do the right thing,” says Mike Aldred. Justin Shilling, co-captain of the bowling team, “was smart beyond his years, hilarious without even trying,” said his close friend Olivia McMillan when she stood up at a school-board meeting. He died the day after the shooting, and two days later, a vigil gathered at McLaren hospital as his body was taken off life support and wheeled into an operating theater where he donated his organs.

The 2015 FBI report on preventing mass violence defines leakage as the messages a prospective shooter sends, like a bread-crumb trail, to signal his intentions. Leakage can come in the form of obvious statements, in conversation or social-media posts, but it can also be subtle or private: the theme of an art project, between the lines of an essay, an item on a scribbled to-do list found in the aftermath.

The night of the 30th, after the shooting, Jehn was on a burner phone texting with Pennock about selling her horses. “Thanks for not judging, unlike the whole world,” she wrote.

“I know you and James and this doesn’t even remotely make me think it was your fault,” Pennock wrote back.

“I wish we had warnings. Something. He’s a good kid. They made a terrible decision.”

“There probably were warnings but nobody saw them,” Pennock responded. “Hindsight is always 20/20.”

After the shooting, when East Street became a crime scene, a police detective took photographs of the house. The kitchen was orderly, with a bread box on the counter, and coffee cups on a shelf, and new bags of pet food on the island. In the master bedroom, the detective photographed the unmade bed. A pair of pajama pants lay entangled with the sheets, the empty SIG Sauer case on top.

Ethan inhabited two bedrooms off the kitchen in the house, his belongings spread so completely across both that it was impossible to tell where he slept. In the photos, the rooms are spilling over with laundry and junk. Full and empty bottles of soda and water, stuffed animals, underwear, lip balm, and a geometry text are strewn over two beds. On one wall hang two giant shooting-range targets in the shape of human torsos, which are riddled with holes. There are also old soccer trophies and medals and model schooners on a shelf; toy airplanes and cars and a miniature Packers helmet crowd the nightstand along with a collectible Nazi coin and a small dish of bullets.