Marriage has a profound effect on the financial lives of women. And the financial lives of women have a profound effect on their marriages.

Why publish a long-form financial investigation about heterosexual marriage? Well, there’s a wealth of available data that proves it’s one of the most-studied social phenomena. And because its effects are surprising — and often troubling. Journalist and author Lisa Miller explains why.

“Happiness in marriage is entirely a matter of chance,” wrote Jane Austen, perhaps history’s shrewdest and most insightful marital documentarian who also wrote great novels. If you’ve read those novels, you’ll know that Austen understood, as deeply as many of us women who came after her, how the prospect of a lifelong commitment pits a woman against herself. Isn’t the yearning to be cherished by a soul mate always at odds with a woman’s ambitions, sense of self, and desire not to change all the diapers? Of course, Austen was also one of history’s great marriage optimists — her novels always end with people getting happily hitched. But I think if she were writing in 2019, even Austen might find herself daunted by plotting a heroine’s course when it comes to the institution of marriage.

As a woman working in journalism and publishing, I know lots of young, professional women. They’re smart, ambitious, and they presume their independence. They are editors and writers (my trade), but also psychologists, artists, management consultants, medical students, lawyers, business owners — even an accountant who works in film and television doing payroll, an exotic profession to numerically challenged people like me. What all these young women have in common is that they were raised to want — to expect — professional success: the partner track, a bonus, a byline, articles of incorporation. They relish the agency that comes with a paycheck; no one can tell them what to do — after all, 70% of women between ages 18 and 34 are in the workforce today(1), and opportunity breeds autonomy. And the more they earn, the more women do things with their money that might discomfit the very mothers who insisted they fight for their salaries: pay for dinner, build wine cellars, work on their muscle definition, buy property, raise kids on their own.

[Source](https://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/emir.kamenica/documents/identity.pdf)

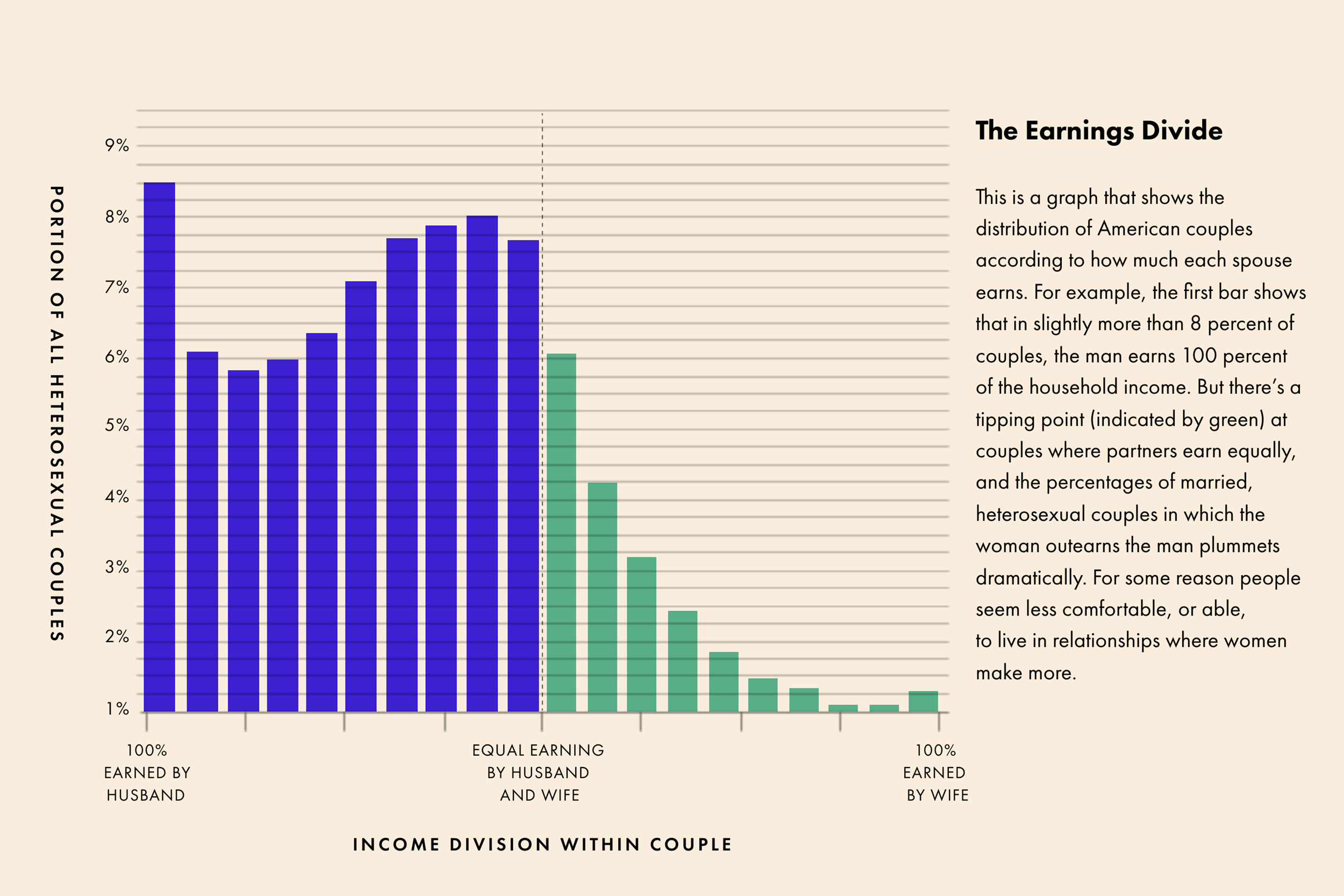

So, yes. Women today are living in a new world of female power and independence, hurtling themselves toward old glass ceilings and expressing themselves physically, sexually, and romantically in ways never seen before in the history of gender. But if you think these developments have revolutionized the old, heterosexual conventions around mating and marriage, consider the findings of these three studies:

The first is from 2006 — a year when nearly half of all first-year law and medical students were female, when it was hard to turn on the radio without hearing Pink railing against “stupid girls.” The experiment was conducted over 14 weeknights, during which 392 graduate students participated in a speed-dating exercise (2): 10 women would sit at small bar tables, and 10 men would circulate, sitting together for four-minute get-to-know-you sessions before moving on. Each partner would then rate the traits of the other on a clipboard their partner could not see. What did the results show? Men desired attractiveness in women, more than they did intelligence — and by a huge margin: nearly 20%. They did not value ambition in a woman when they thought it exceeded their own, and they were not inclined to invite a more ambitious woman on a second date. Women, on the other hand, liked men who seemed intelligent and came from affluent zip codes, preferences the researchers linked to theories of evolutionary psychology: “Female choice reflects women’s desire to find men who can find resources to aid in the upbringing of their offspring,” they wrote.

The second study, conducted several years ago, involved male and female students in an elite MBA program who were given a questionnaire about their ambition (3), their appetite for long hours and travel, and their income requirements. Participants were told that their answers on the questionnaire would help them gain access to prestigious internships. When female respondents believed that the forms would be viewed only by staff at the university career office, their answers nearly matched their male peers. But when they thought the form would be seen by their peers — which is to say the men in their classes, i.e., the men they thought of as possible husbands, the “market” of mates — they dramatically undersold themselves, asking for $18,000 a year less than the men, and they downplayed their desire to work long hours or travel.

The third study, though, is perhaps the most shocking, and sent a tremor through the universe of social scientists who study the economics of marriage. In 2015, a prominent researcher named Marianne Bertrand published a paper showing that dating couples (4) are less likely to marry when the woman earns more than the man; that even when a woman has the potential to earn more than her husband she is unlikely to do so. But possibly more disturbing was the finding that when a wife does outearn her husband by more than 50%, she is likely to quit her job or scale back within two years in order to “correct” the traditional gender imbalance; and that if she persists in earning more, she will take on more housework in order to restore gender norms to their “natural order.” “Women are bringing personal glass ceilings from home to the workplace,” Bertrand wrote.

When a wife does outearn her husband by more than 50%, she is likely to quit her job or scale back within two years in order to “correct” the traditional gender imbalance.

Maybe this is why I sense so much anxiety from my young friends when they talk about marriage — the ambivalence, the wavering, the second-guessing. Women today are caught in a vise, squeezed between their vision of independence (to be the woman with the roller bag hailing the cab or picking up the check in the Michelin-starred restaurant) and the gender roles codified by the Church Fathers and enforced for thousands of years by jurists, neighbours, and governments. At the bottom of all this is the nature/nurture dilemma. Are women “wired,” as some believe, to care for hearth and home? Or do they assume that role, sometimes against their self-interest, over centuries of cultural training? Think of trying to hold all this in your head: Women desire to pay their own way, and, at the same time, be courted; men say they want to share child-rearing but are also compelled by their urge to provide. Maybe that’s why the average age of first marriage in the U.S. is 28, the highest it’s ever been. Why more than a third of millennials say they plan never to marry at all. Maybe — caught amid contradictory signals about what they should do — a whole generation of women is suffering from an existential state of ambivalence.

This seems like an important moment to ask some questions about the whole nature of heterosexual marriage (we’re focusing on that particular version of marriage for the simple reason there’s just way more, and more robust, data on marriages between men and women — but these questions apply to everyone). Questions like: What is marriage? Is it a financial arrangement, as it once was? Is it about love, sex, companionship? About the raising of children? How does state-sanctioned monogamy jibe with the 21st century demand for the freedom to make one’s own choices? The desire for power? Or success? Do our relationships make inequalities — the wealth gap, the wage gap, the dishes gap — worse? Is the whole thing able to evolve? And if it can’t, could it just disappear?

2. Women with Their Own Money Have Healthier Marriages

The economist Anna Aizer is interested in poverty, especially in the problems besetting poor women. As a young professor at Brown University, Aizer began to study domestic violence, which afflicts the poorest women five times more than women who earn more than $30,000 a year. But the ramifications of what she discovered, in a paper she published in 2010 (5), goes far beyond the study of poverty: As women begin to earn their own living, she found, domestic violence goes down.

(6)

This is not just because women who work are less frequently home and therefore less vulnerable to being beaten. Or because a woman who isn’t being beaten can reliably show up at work. Aizer’s research shows a more fundamental shift: A woman who earns money has the power to leave, and the power to leave has a direct effect on her boyfriend or partner or spouse. In the past several decades, the incidence of domestic abuse has plummeted. At the same time, women’s earnings have risen, and job opportunities for them – especially in service and health care (6) – have grown. Research suggests that these two things aren’t coincidences. Nearly 10% of the drop in abuse is due to the rise in the so-called “outside option” for women — the ability of one partner to leave the relationship if he or she wants to.

Aizer also showed that this effect goes beyond individual couples. Even if a woman herself does not work or earn money, the fact that other women do — her neighbors, her sister, her friends, the people at church, the women she sees on TV — protects her from being beaten, because her partner understands that she has somewhere to go where people will take her side and support and protect her.

To develop her algorithm, Aizer used the “household bargaining model” of relationships, the old idea in economics that each person in a family — or household — holds “chips” of greater and lesser value that allow them to negotiate the terms of family relationships. Bargaining chips — units of power — are generally: income and “household production,” also known as labour (doing dishes, making dinner, going grocery shopping, child-rearing, doing the laundry, providing sex, etc.). The “outside option” is one of those chips. Neither partner needs to exercise the outside option to have bargaining power, nor does he or she have to mention it — the outside option needs only to exist to affect the dynamics of a marriage.

The outside option is an incredibly powerful medicine for the health of a marriage. Financial dependence isn’t good for anyone.

“A credible threat is enough so that the partnership survives,” Aizer explained to me when I spoke with her on the phone. And for poor women, the options are greater: the growth of low-skilled jobs in typically “female” industries like service and in health care far outpaces the growth of low-skilled jobs that typically go to men, like in factories and mines. “Are there more opportunities for women?” Aizer asks. “If so, that means the threats are credible.”

The outside option is an incredibly powerful medicine for the health of a marriage. Financial dependence isn’t good for anyone. It’s linked to drug and alcohol abuse, anxiety, depression, and domestic violence. Aizer warns that it’s not easy for society to change. “It’s costly to go against a norm. There may be psychic costs. There may be direct costs. But over time, norms will change. They’re not God given — even though they outlive some of the incentives that created them.”

3. Women Are Poised to Earn More Than Ever, While the Prospects for a Lot of Men Are Dwindling

In every developed country and at every level of the socioeconomic scale, women are better positioned to be earners than ever before. For one thing, they are better educated. In the U.S., in 2016, women earned 30% more bachelor’s degrees, 45% more master’s degrees, and 13% more Ph.D.’s. In Canada, in 2016, 40.7% of women had a bachelor’s degree, compared with only 29.1% of men. Throughout Europe, an estimated 10% more women have graduated college than men (7). This surge in female achievement is having its effect on marriage. Whereas husbands used to be better educated than their wives, as a general rule, that dynamic is beginning to reverse itself: 20% of wives have more education than their husbands, according to Pew, a trend that the pollsters predict will continue to grow.

With all this education, women are well prepared to enter the workforce. And they expect to work — both out of ambition and of necessity. They have an appetite for it. In Canada, 61% of women over age 15 work, up from 53% in 1983. In the U.K., 58% work, up from 46% in 1983 (8). Rates of working mothers are astonishingly high in the poorest countries in the world (not surprisingly), but they’re high in the developed world too – it’s now an unremarkable fact of life that young women are more likely to have had working mothers than not. In the U.S., 70% of women with children work, a number that has been stable since the 1990s. Dual-income families have become the norm: In 60% of married couples with kids, both parents work.(9)

High-earning women gave men permission not to work as hard. (Or, was it the other way around? That men who didn’t like to work as hard sought out — and married — high-earning women?)

But just as the prospects for women have gotten better, the prospects

for men in certain segments of society have gotten worse. Recent

history has witnessed the evaporation of mid-level corporate jobs that

provided stability for generations of family men; globalization and

automation are in the midst of destroying whole sectors of good

manufacturing jobs that have been traditionally male. 42% of American

mothers — 42%! — are the primary or sole earners in their families, up

from 11% in 1967. The percentage of Canadian women earning

“significantly more” than their husbands has doubled, from 8% in 1985 to

17.3%.(10) Women see these trends clearly, and their panic

is understandable: Before any kids or unemployed husbands even enter the

picture, many women are already swimming in debt. Two-thirds of

outstanding college loans are held by women, an unhappy consequence of

that educational boom.

What happens when those trends collide inside a marriage? In a 2018 Ph.D. thesis, an economics student at Harvard named John Coglianese (11) coined the rather sophomoric term “in and outs” to describe a social phenomenon he saw among his peers. Men, usually well educated and with good employment prospects, were dipping in and out of the workforce. These men usually identified as professional people, but their alliance to full-time work was casual, and when they were unemployed, they accomplished very little. According to their own responses on questionnaires, married “in and outs” did not use their downtime to help more with chores or childcare. When he studied their leisure time use, Coglianese found they spent it “primarily watching television.” He wondered whether this phenomenon was linked to the “gig economy” — professional people cycling in and out of jobs, freelancing as an identity rather than a temporary state. But he discovered far stranger underpinnings to his findings: It seemed that the common denominator among married “in and outs” was that they were partnered with high-earning women. “In and outs have risen most in households experiencing the largest growth in female wages,” he wrote, suggesting that proximity to high-earning women gave men permission not to work as hard. (Or, was it the other way around? That men who didn’t like to work as hard sought out — and married — high-earning women?)

The lowest rate of psychological problems occurred among men working at white-collar jobs, whereas the highest rate was among unemployed men who formerly worked at manual jobs. Women’s mental health was much less dependent on employment.

What does the future look like to a woman who’s just graduated college and sees, on one hand, a future of student loan repayments, and, on the other, a cohort of women a generation older who are raising children with a husband who doesn’t work — and, if he’s unemployed, he may be depressed as a result, drinking or brooding or worse? Who may even be unemployed as some kind of psychological response to his wife’s accomplishments? Let’s not forget that unemployed men often wreak havoc on marriages, maybe because their egos can be so tied up in earning, because a man’s identity can be so inextricably tied up in what he does for work. Spanish psychologists showed in 2004 that the lowest rate of psychological problems occurred among men working at white-collar jobs, whereas the highest rate was among unemployed men who formerly worked at manual jobs. Women’s mental health was much less dependent on employment.

More simply: Couples in which the man does not work full-time are 33% likelier to get divorced within a year than couples in which the man has a job, according to new research from a Harvard sociologist.

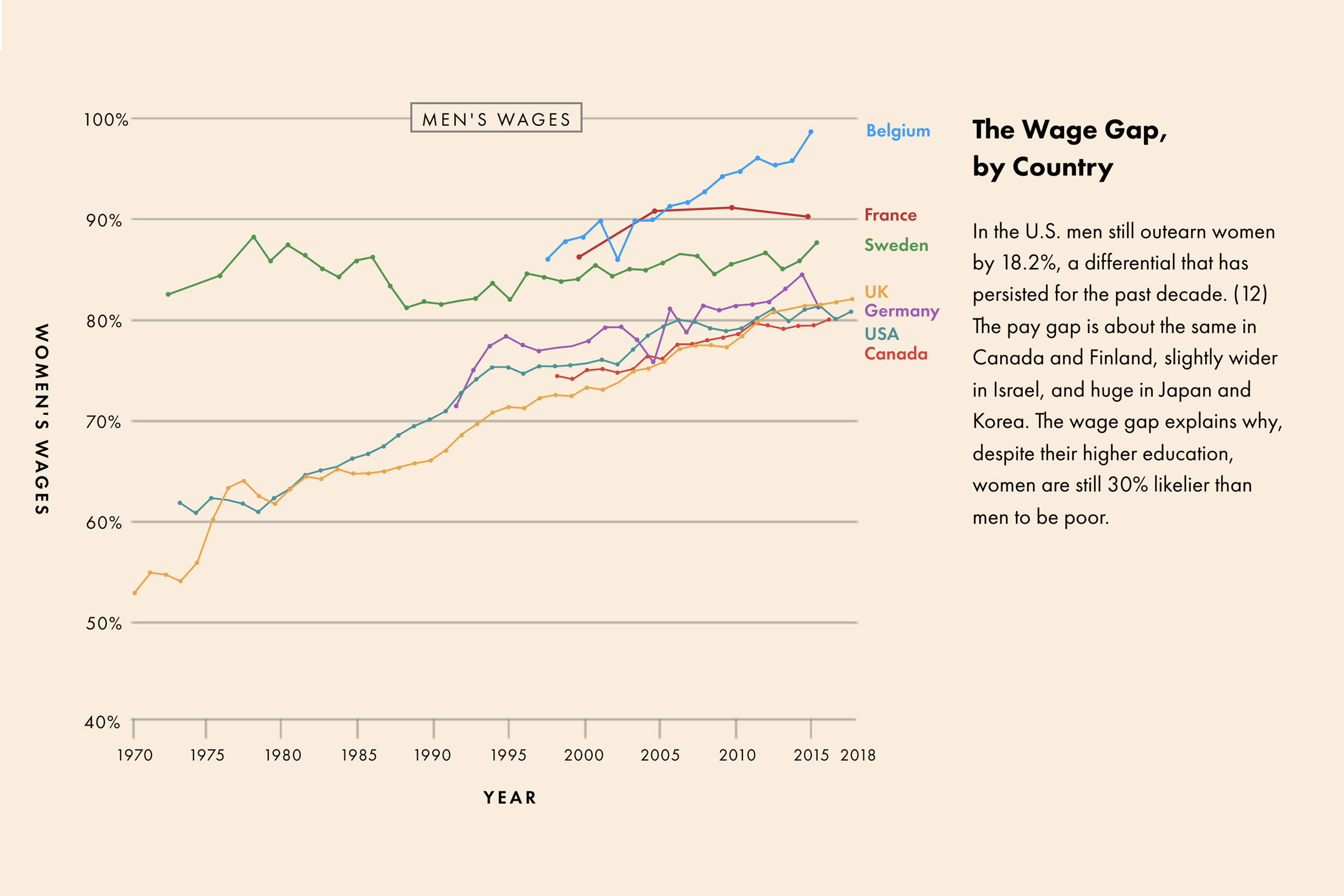

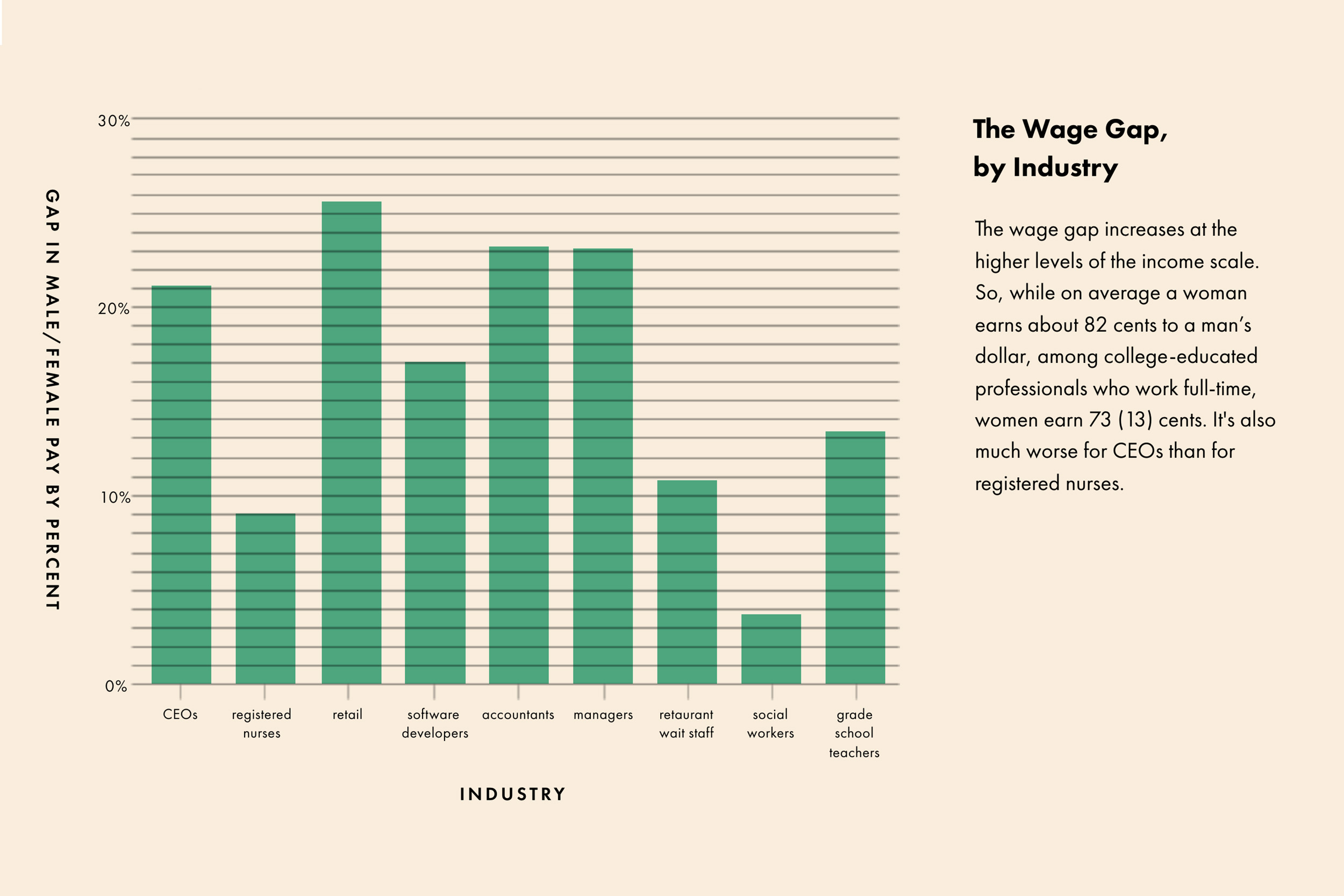

4. Sure, Women Will Be Better Educated, But They’ll Still Be Paid Less: The Strange Phenomenon of the Wage Gap

[source](https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gender-wage-gap-oecd?time=1970..2016&country=BEL+CAN+FRA+DEU+SWE+GBR+USA)

[source](https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/C467_2018-Occupational-Wage-Gap.pdf)

[source](https://statusofwomendata.org/explore-the-data/employment-and-earnings/employment-and-earnings/#TheGenderEarningsRatio)

[source](https://www2.census.gov/ces/wp/2017/CES-WP-17-68.pdf)

[source](https://www2.census.gov/ces/wp/2017/CES-WP-17-68.pdf)

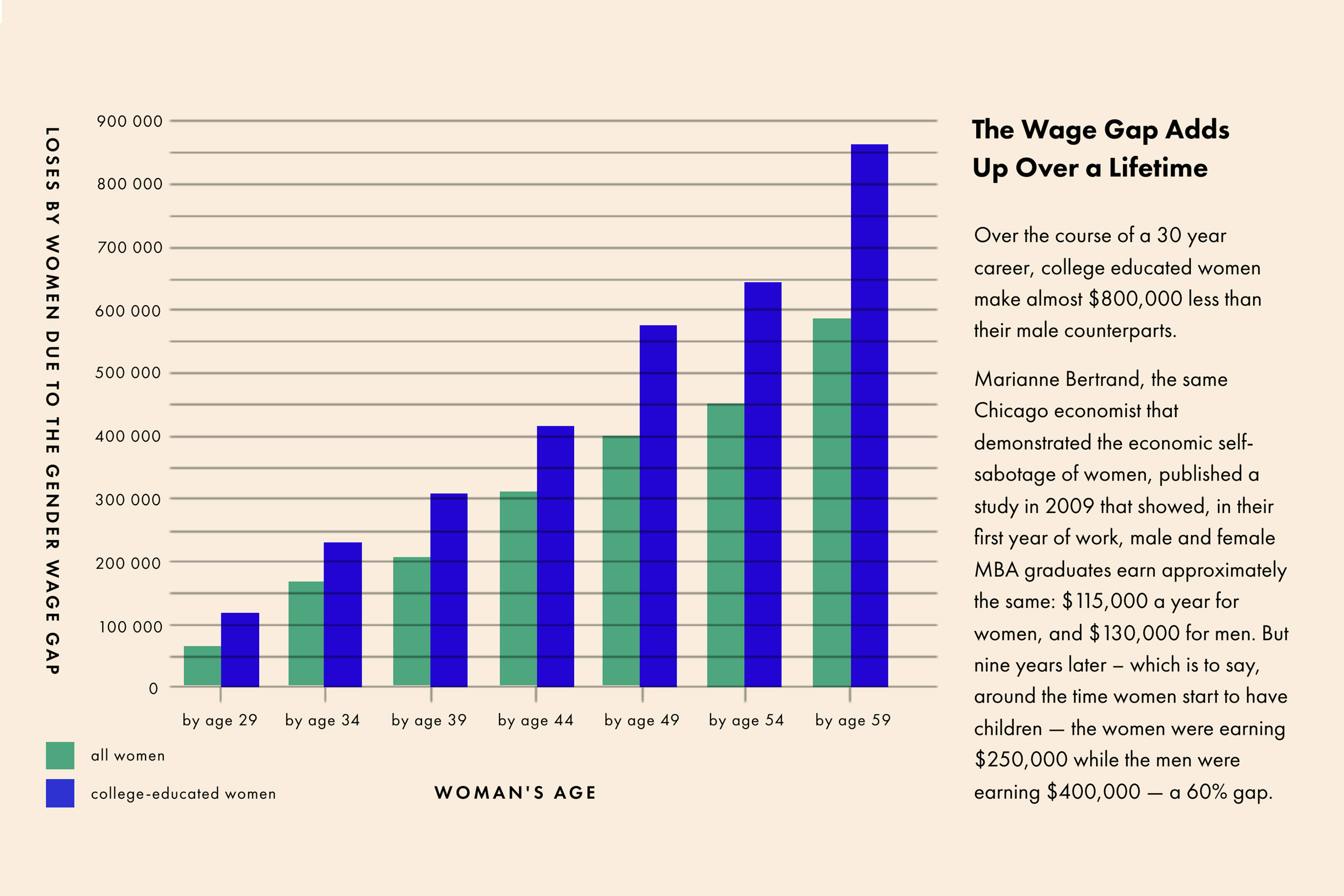

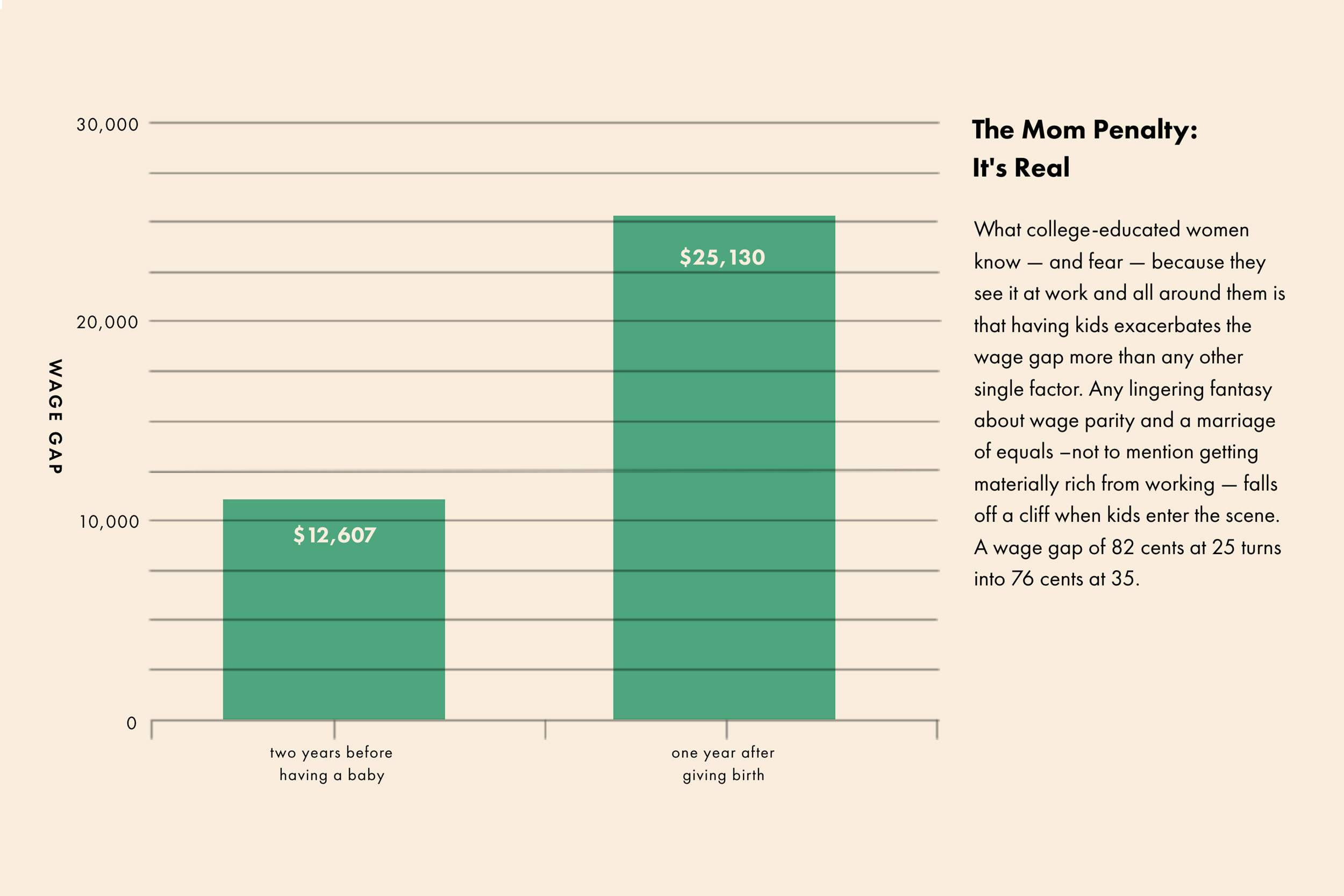

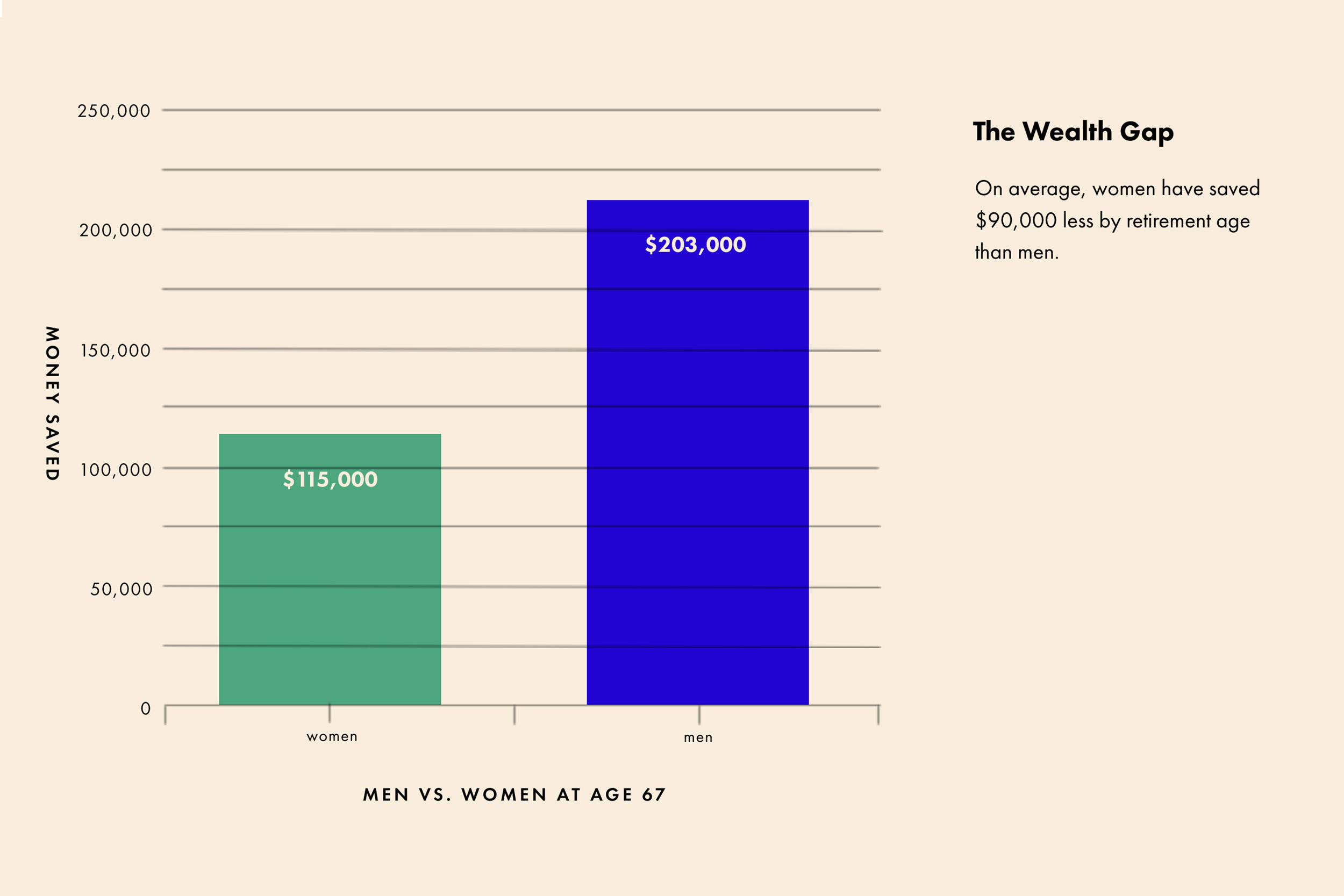

The wage gap isn’t just about paychecks and bonuses. It’s about how that amplifies over time, changing the realities and choices women have — the size and viability of the “outside option” that Anna Aizer studied. By some estimates, pay inequity costs a woman $800,000 over a lifetime of work; by others, it’s more: a million or two. Lower wages correlate to lower rates of savings. Lower savings correlate to lower wealth. The average American man has $78,000 in his 401(k). The average American woman has half that much. And, as we all know, those differences become vast over the course of a life thanks to the power of investing and compound interest.

A woman whose savings have been stunted for a lifetime is certainly more likely to feel like she can’t afford to leave her marriage — a sense of being stuck that is a major predictor of marital unhappiness.

5. The History of Marriage as an Institution Is a Money History — and It’s a History of a Kind of Financial Imprisonment

When the armies of liberated women made their assault on American workplaces in the 1980s, their shoulder pads doing double duty as a kind of protective armor, much of the rest of the world — which is to say the world I grew up in, where mothers stayed home and put a snack on the table at 3:20 p.m. — looked at them as gender traitors, betraying their biological imperative to stay home, raise kids, and clean up after finger painting. But in truth, through the long arc of history, women have always worked. It’s the idea of women having their own money that’s new.

During the Middle Ages, some of Europe’s richest women opted not to marry at all but to enter convents (or start them, like small businesses) instead. Why? They may have been fervently, devotedly Christian women, but there’s also this: In a time and place where marriage meant the ceding of one’s wealth and property over to one’s husband, a religious life was one way for a woman to retain some ownership and control. Until as late as the middle of the 19th century, married women had no legal rights: In England they were like children, unable to earn, keep, and control their money and property, to attain financial status on their own, and to personally benefit from their labour. Women couldn’t even write wills — at the moment of marriage, a woman turned over the rights to property, rents on property, future profits from the sale of real estate and belongings.

And in most places, any money a woman might inherit from her father would pass to her husband instead.

Wealthsimple is investing on autopilotLearn more

But in the middle of the 1800s, a new kind of reform movement started, an outgrowth of the same ideas that propelled the abolitionists. Reformers began to argue that women needed protection from what some of them called unconscionable “masters”: irresponsible, drunk, or profligate husbands. And in the U.S., one by one, states began to pass “Married Women’s Property Acts.” (14) In New York, for example, the law allowed women to keep the money and property they possessed when entering marriage; to control the money and property they accrued themselves within a marriage; to receive gifts and inheritances from third parties, and to retain them; and to enter into contracts. Other states (Connecticut, Texas, Massachusetts) passed laws that allowed women to write wills, and so pass their wealth along a matrilineal line; some made provisions for children to stay with their mothers in the event of a divorce (although it would be another century before courts recognized divorce as “no fault” and forced men to pay money to their wives who didn’t work at jobs).

The dowry, ironically enough, was a crucial element of that reform. In the ancient world, dowries in many cases compensated for the intrinsic inferiority of females: Daughters were just one more mouth to feed; men with good prospects needed incentives to take them off parents’ hands. But in more modern times — that is, once women began to fight in the courts to keep the money that came to them — the dowry became a singular tool of female independence and marital satisfaction. Women began to receive legal rights to their money in the mid-19th century, but they had little means of earning it. In such eras, when women had no other legitimate means of supporting themselves, the money and property parents provided at the outset of marriage insulated them from the vagaries of financially irresponsible husbands. “It may be conceded that the financial independence of woman would in the main be a solid guarantee of her happiness in the marriage relation,” wrote one English reformer in 1888. Even without the opportunity to work, a dowry — if she could keep control of it — gave a woman something akin to an outside option.

6. Even More Intransigent Than the Wage Gap Is the Diaper Deficit

In nearly every permutation of the marriage agreement, women do more of the housework.

On an average day, American men do 15 minutes of housework, while their wives do 45. (15) In Britain, women do 60% more housework than men. In Sweden, they do 45 minutes more. But what’s shocking is that, according to a recent study by a husband-and-wife team of researchers, men do even less housework than the norm when their wives earn more than they do, and the researchers speculate that’s because men’s masculinity is threatened by the imbalance. As one of the researchers put it to an interviewer: “She might earn all the money, but I’m not going to do dishes.” Meanwhile, both men and women feel that the more they earn, the less housework they should have to do, but when a woman earns more, the first thing she does is spend a chunk of her paycheck on outside household help.

When men and women shared household chores — laundry, grocery shopping, child care, dishes – they had more sex, a total of 6.8 times a month, than when women did them alone.

It’s true, though, that men have started to take on more, incrementally. And marriages are happier when couples share the household labour. But there are some caveats to that. In 2016, researchers showed that when men and women shared household chores — laundry, grocery shopping, child care, dishes – they had more sex, a total of 6.8 times a month, than when women did them alone. (16) It didn’t matter who earned more — unless the woman was the only breadwinner; then sexual frequency and satisfaction dropped precipitously. “It might be emasculating to be a so-called house husband in a way that sharing equally is not,” Amanda Miller, one of the paper’s authors, told me in an interview. “The ‘house husband’ is still not what we have in our heads — it’s not a cultural model we have right now.” Other research has shown that men who are financially dependent on their wives are more likely to cheat than men who share the earning responsibilities.

These norms are also more resistant to change than you might think. You can’t, it seems, just casually implement some progressive policies and watch the dishwashing and diaper-changing rules of the world disintegrate. Consider the results of a study published in 2018. (17) The research took place in Denmark, a country famous for its gender parity — the Danish have excellent social supports for families; both mothers and fathers get a year of paid leave after the birth of a child; there’s subsidized day care for kids under 3. It seems safe to assume that in such an environment men would feel supported in opting out of the provider role and into the role of child-raising. But the researchers discovered that just 10% of men use the state’s generous optional parental leave policies. It seems that unless men and women are pushed into parity — as in Iceland, where the government gives 13 weeks of leave specifically to fathers (and 90% of fathers take it) — parents tend to revert to the traditional gender roles. And an unsurprising corollary: Danish women who don’t have children earn nearly as much as men, but their earnings drop sharply after the birth of their first child, resulting in a 20% wage gap over time.

7. A Little Light at the End of the Gender Stereotype Tunnel

It’s hard to break a bad habit, and yet it’s possible. Christine Schwartz, a sociologist at the University of Wisconsin, has shown that among the youngest couples, especially those in Europe and those whom she calls cohabitators (with kids but not married), love and family can withstand the stress of a woman outearning a man. (18) Schwartz’s work begins with a question. Given the assumption that women’s education level is going up, with no sign of stopping, and that will correlate to earnings eventually — what’s going to happen when more and more women begin outearning their husbands?

Women with high levels of financial independence preferred good-looking men over earners at a very high rate — at about the same level as financially independent men.

For decades the assumption has been that when a woman outearns her husband, the couple is bound for divorce. Lots of older studies have suggested as much. But Schwartz looked at it differently. She looked at three different cohorts of couples: some who married in the 1970s, some who married in the 1980s, and some who married in the 1990s. Among the older couples, divorce patterns followed the old expectation: Even when women outearned their husbands slightly — by a single percent — divorce became a probability. But couples who married in the 1990s and later — younger, more progressive-minded people — tended to stay married even when the wife earned a lot more than the husband. (The only circumstance that predicted divorce in Schwartz’s research was when the wife earned everything and the man nothing.) It seems, in other words, that these roles aren’t simply biological, they’re more social, and as things change in the world, couples seem happy for them to change in individual relationships.

And there’s a bonus: Schwartz also showed that young married couples in which the wives outearned the husbands were more prosperous — they averaged 30% more total earnings than those in which the wives earned less. Maybe this is because even with the flattening of men’s wages, a part-time husband still earns more than a part-time wife thanks to the wage gap.

Meanwhile, as the studies cited at the beginning of this piece, men have long been presumed to choose their mates on the basis of their attractiveness and fertility while women choose mates for their ability to provide, gender norms that persist in every socioeconomic stratum. But what happens when the facts on the ground change? When women have financial autonomy, do their mate preferences change? It turns out they do. A few years ago, evolutionary biologists in Scotland asked more than 1,500 female professionals to fill out questionnaires that asked whether they preferred men with “physical attractiveness” or “good financial prospects.” Women with high levels of financial independence preferred good-looking men over earners at a very high rate — at about the same level as financially independent men; women with low financial independence favoured men with good prospects, which could be seen for them as more of an evolutionary necessity. The researchers proposed that their findings suggested that when women become providers, they seek out mates who will help them optimize their gene pool — creating healthy, beautiful children — and not, necessarily, to pay the rent. Researchers in Finland, similarly, recently found that men are more likely than women to say they want a partner with high intelligence and a good education — traits usually linked with high earnings potential. In Germany, more women than men say they want a partner who has good housekeeping skills. The 2018 British Social Attitudes survey revealed that just 8% (19) of 18 to 25 year olds agreed with this statement: “A man’s job is to earn money; a woman’s job is to look after the home and family.”

Perhaps the stubborn quality of gender roles is more about feeling like you’re living up to expectations — that you’re not disappointing your spouse (or yourself), that you’re essentially lovable — than it is biological. In 2015, a professor named Lamar Pierce showed that for couples in which the woman earns more — even just a little bit more — husbands were more likely to use medication for erectile dysfunction and wives to use anti-anxiety drugs. But when the couple agreed to the role reversal early on in their relationship, before they wed, then they had no such issues. (20)

8. Oh, Right. And There’s That Thing About Love and Generosity

It’s easy to see this marital dilemma as an either/or — a world of women guarding their outside option or succumbing to the pull of domesticity; a world of men abandoning their financial obligations to watch TV or ferociously striving toward the next promotion at work. It’s easy to see marriage itself as a choice: a cold financial contract that preserves each partner’s independence, or a total commingling of everything. Selfish or selfless. Out or in.

But what if the secret to marriage is something else, an alchemy of self-preservation and the deepest generosity?

Ashley LeBaron is a Ph.D. student at the University of Arizona who studies the effects of money on marital bonds. Her work has focused on materialism in marriage. Specifically, whether any relationship factor can mitigate the marital unhappiness that’s been proven to exist when both partners are very materialistic — concerned, as she puts it, with money and possessions. “The top predictor of marital conflict,” she says, “is when a husband perceives a wife as ‘very spendy.’ ”

And what LeBaron found was extraordinary. Except in instances where husbands earned all the money and entirely controlled access to the couple’s bank accounts, it didn’t really matter who earned how much or whether their accounts were shared or separate. She found that what mattered most was how couples spoke to each other about money, how they worked out disagreements, and — mostly — how their commitment to their partnership superseded their desire for stuff. What LeBaron found was that more than the wage gap, more than good public policy or bad public policy, more than who earned how much, the happiest couples prioritized their coupledom and worked out their disagreements over money with the preservation of the marital unit at the forefront. “In the past,” she says, “there’s been too much dependence going on, and some women were stuck. I think too much dependence is a problem. But I wonder if, in recent times, we are moving toward too much independence. My bank account, your bank account.”

It’s not as simple as merging your money though — after all, a third of people with joint finances lie about money to their partners, failing to mention purchases large and small or establishing secret bank accounts. Twenty percent of people who share credit cards admit to spying on their partner’s statements. No matter how much people insist they want to share and trust their partners, they also know that they can’t be too careful. But what I think LeBaron would like to see is something more magical than password-protected bank accounts and spyware and more difficult than capitulation to the way it’s always been. The trick is for each partner to hit that Jane Austen balance: enough independence with enough acquiescence to the whole. “Where two people are separate,” LeBaron says, “but where the relationship is … I don’t want to say ‘the relationship is first,’ but kind of.”

So put your relationship first. But only kind of. Easy, right? Well, no one ever said marriage was easy.

First published in WealthSimple Magazine

Header animation built by Jorge Olivares.

1) Bureau of Labor Statistics, retrieved Jan 15, 2019

2) “Gender Differences in Mate Selection, 2006documents/genderdifferences.pdf)”

(The experiment was conducted over 14 weeknights, during which 392

graduate students participated in a speed-dating exercise)

3) “Acting Wife’: Marriage Market Incentives and Labor Market Investments,” 2017

4) Gender Identity and Relative Income Within Households, 2015

5) “The Gender Wage Gap and Domestic Violence,” 2010

6) Going Digital, the Future of Work for Women, 2017

7) Statistics Canada, 2016; [Eurostat Gender Statistics(https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Gender_statistics#Education), 2016

8) International Labour Organization, 2018

9) U.S. Department of Labor, 2017

10) Statistics Canada, 2016

11) The Rise of In-and-Outs: Declining Labor Force Participation of Prime Age Men, 2017

12) OECD, 2019

13) Economic Policy Institute, 2017

14) Library of Congress, Retrieved 2019

15) Division

of House Chores and the Curious Case of Cooking: The Effects of Earning

Inequality on House Chores among Dual-Earner Couples, 2014

16) The Gendered Division of Housework and Couples’ Sexual Relationships: A Reexamination, 2016

17)Children and Gender Inequality: Evidence from Denmark, 2018

18) Trends in Relative Earnings and Marital Dissolution: Are Wives Who Outearn Their Husbands Still More Likely to Divorce?, 2016

19) British Social Attitudes Survey 35, 2018

20) In Sickness and in Wealth: Psychological and Sexual Costs of Income Comparison in Marriage, 2013

21) Tightwads and Spenders: Predicting Financial Conflict in Couple Relationships, 2016