When did Elinor Carucci enter my apartment and take photos of my life? This was exactly how I felt looking at her new book, Midlife, a gorgeous documentary account of domesticity, 20 years in.

Photo: Published by The Monacelli Press and courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery

There is the messy kitchen counter, unpicturesque. There is the couple (at the same counter) paying bills and unpacking groceries, each frame a frozen section of time, implying decades of repetition of household chores. The teenage daughter gazes at the camera with a look of rebelliousness, while her twin brother seems more delicate. The husband is sheepish, aware that he’s been consigned to the dim border areas of parenthood. One picture, of the couple posed in the semi-dark, is titled You Know More of the Parenting Falls to Me. The wife, standing in the refrigerator light, accuses her husband; he is shadowed, shirtless, and looking away.

Photo: Published by The Monacelli Press and courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery

This is Carucci’s life, of course, not mine. And at the center of it is Carucci herself, curiously scrutinizing the moment she’s in. She documents the gray hairs erupting from her head as well as at her crotch and the crinkling skin that, magnified, resembles a CGI desert. In many of the photos, she is naked. Carucci hugs, she loves and scolds, with her drooping breasts and thinning lips on display as if to say, This is what happens in real life, in a real marriage, with real children, in a real apartment where there isn’t quite enough square footage to store decades of accumulated crap when no one has the removal of crap at the top of their priority list. Women — mothers — have been aging forever, but that has always been more an occasion for self-help than a subject for art.

So intimate are Carucci’s photographs that when she opened the door to her apartment, I was surprised to realize we had never met. Her home in Chelsea looks as it does in the photos. There is the kitchen counter, now laden with a small dish of almonds and a cup of coffee; across it stands the artist — small, wiry, still beautiful but not as blatantly desirable as she was in her previous collections Mother and, before that, Closer. We immediately launch in, talking about our graying hair, where our respective children go to high school, commiserating over our imperfect grasp of the martial art that is parenting teenagers: What is intrusive? What is support?

Photo: Published by The Monacelli Press and courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery

As she begins to tell me a story about her uterus, she is interrupted by the sound of jackhammers outside. A new building is going up next door, she explains, and in a few months it will block the natural light that floods her front room, not ideal for any homeowner, but tragic for a photographer; she and her husband are planning to cut new windows high up in the wall that faces the new construction. With dark humor, Carucci recognizes the stupid way that life in Manhattan can redirect even the most countercultural people toward their own self-interest. “Whatever we talk about, we always end up talking about real estate in New York. My uterus! But also,” she laughs at herself, “losing my window!”

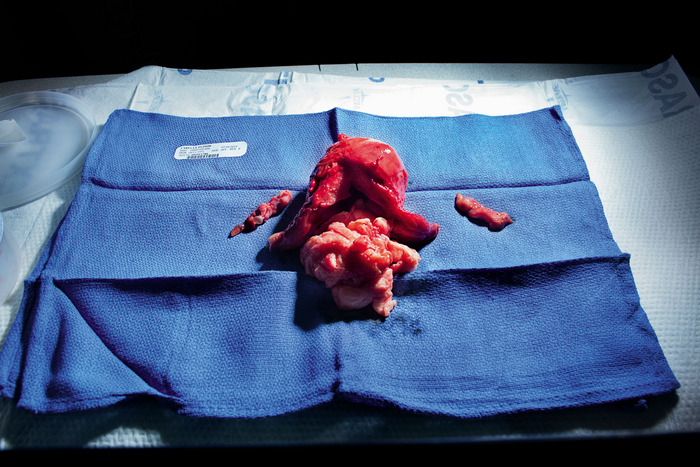

About two-thirds of the way through Midlife, without fanfare or introduction there is a photograph of Carucci’s uterus, splayed on a blue hospital towel, looking like organ meat from a butcher shop or a piece of veal. In her early 40s Carucci had a hysterectomy, a surgical solution to hemorrhagic monthly bleeding, and common enough (a third of women have their uteruses removed before age 60), but still taboo, and the prospect of which filled Carucci with grief. Her instinct was to photograph it, which she explained to her surgeon, who understood. (“I love her!” Carucci exclaims.) So Carucci hauled two gigantic strobe lights to the hospital on the morning of her surgery, and then awoke from anesthesia to the hubbub of dissent. Apparently, someone in the hospital’s protocol department thought a patient photographing her own uterus wasn’t such a hot idea, and she and the surgeon were arguing.

As she was coming to, her husband, Eran, got into her face. “He’s like, ‘They’re taking your uterus away! Are you up? Are you up? You have to take the picture now.’” Carucci directed him to set up the strobes, and the surgeon ran over to her bed.

“She’s up! She’s up!” the doctor cried, turning her back on the source of the conflict. She stood before Carucci’s bed, “holding my uterus in a little bucket,” Carucci remembers. And then as carefully as if she were handling a newborn, the surgeon arranged the uterus on the towel, artfully displaying the Fallopian tubes as well as the fibroids that had caused all the bleeding. “I took maybe five or six shots. I had the good lens, but it’s manual focus, and I was really nauseous. And then they took my uterus away and I went back to sleep.” Carucci adds that if she weren’t a photographer she’d be a stand-up comedian. Life is just too tragic and absurd sometimes.

Photo: Published by The Monacelli Press and courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery

In an essay at the back of her book, Carucci flips the bird at a culture that urges middle-aged people to emulate youth and long-married people to seek to recapture the eros of their earliest months. “We learn to think … that the tenderness and romance of the relationship goes away, so we need to force it, to make time for romance, date nights, and maybe even a weekend away in some hotel,” she writes. But “all those notions made me angry.”

Her photographs insist on a different story. The triumphs of a long marriage (and, more broadly, of family life) are in the “intense collaborations and discoveries of parenting, the deep commitment of time and attention.” The messy kitchen counter, the endless laundry, the bills, the jackhammer outside, the impeded view, the tragicomic encounter with a kind doctor in the midst of unavoidable grief — through Carucci’s eyes, all this is love, evidence that what’s most precious resides in what’s ordinary and imperfect. (Her own favorite photo in the collection is one called Mom Is Being Crazy, a nude self-portrait — joyous, unselfconscious — with her fully clothed daughter whose expression contains every teenage girl’s feelings about her mother: yearning and adulation, as well as mortified disapproval.)

Photo: Published by The Monacelli Press and courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery

In a photo called After Sex, Carucci and Eran lie naked on their big red couch. He, on his side, is facing her, touching her, while she, on her back, protects her breast with her hand and seems lost in her own thoughts. Again, there’s the implication of repetition, the stillness they find together in the moment the photograph is taken, but also a thousand times before and potentially again, the repetition itself a song to middle-aged love. “We get up in the morning,” Carucci tells me. “We send the kids to school. He handles this, I do that, then we go to Trader Joe’s, and it’s amazing! And then we got to the laundry and we have this beautiful, intimate conversation for the seven minutes that we’re there.”

Photo: Published by The Monacelli Press and courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery

As she was finishing the essay, Carucci wavered. She had written that in her middle age, “I joke more; I try to laugh more, I have to. I feel more and hurt more and fear more.” But then, how to end it? The final sentences of the entire collection had to be so strong. Initially, she wrote, “I love more.” But, life got so overwhelmingly complicated sometimes, she wasn’t entirely sure: “Am I really loving more?” she asked me at the kitchen counter. “It’s hard to know. We can’t measure it.” So she changed the sentence to reflect her uncertainty: “Maybe I love more.” And when her editor called her to tell her they were shipping the pages that evening and she had to sign off on her copy right now, Carucci was at Gristedes doing the family grocery shopping. “And I said, ‘Give me an hour.’ And I called my husband. And I was like, ‘Do I love more — he knows me since I was 21 — than I did when I was younger?’ And he said, ‘Yes. Of course you do.’ And I said, ‘Thank you.’”

Carucci called her editor back. “I was like, ‘Take out the maybe. No maybe. I love more.’ I’m middle-aged. And I love more.”