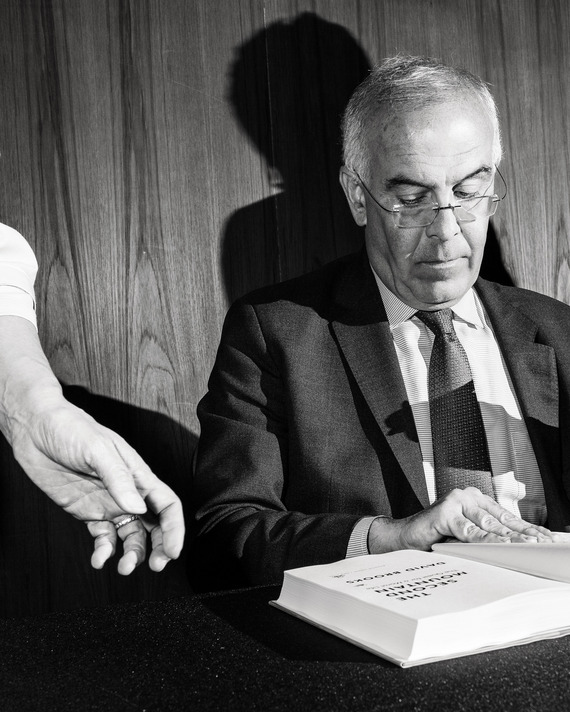

It was 2013,and David Brooks was in the wilderness. Not the literal desert or jungle or anything like that, but the emotional wilderness of an accomplished man who, in midlife, has discovered a deep emptiness at his core. His marriage of 27 years was falling apart. The genteel conservatism in which he was nurtured and raised was morphing into something craven, naked, and raw. Lonely and living alone in an apartment in Washington, D.C., Brooks, 52 at the time, took stock and saw that in his rise to the pinnacle of American punditry, he had failed to make or keep meaningful friendships. And what was happening to him, Brooks writes in his new book, The Second Mountain, was happening on a nationwide scale. “The crisis in our politics is created by the crisis in our sociology and in our relationships — and in our morals,” he told me, looking preppy, eager, and somewhat slighter than I’d imagined, as we sat drinking coffee at a chain restaurant near Carnegie Hall.

It was 2013,and David Brooks was in the wilderness. Not the literal desert or jungle or anything like that, but the emotional wilderness of an accomplished man who, in midlife, has discovered a deep emptiness at his core. His marriage of 27 years was falling apart. The genteel conservatism in which he was nurtured and raised was morphing into something craven, naked, and raw. Lonely and living alone in an apartment in Washington, D.C., Brooks, 52 at the time, took stock and saw that in his rise to the pinnacle of American punditry, he had failed to make or keep meaningful friendships. And what was happening to him, Brooks writes in his new book, The Second Mountain, was happening on a nationwide scale. “The crisis in our politics is created by the crisis in our sociology and in our relationships — and in our morals,” he told me, looking preppy, eager, and somewhat slighter than I’d imagined, as we sat drinking coffee at a chain restaurant near Carnegie Hall.

But Brooks picked himself up. He landed a gig at — where else? — Yale, teaching a class about — what else? — humility, with a syllabus including works by Edmund Burke, Reinhold Niebuhr, and himself. His emotionally arid existence bloomed again, thanks to the loving presence of a woman — Anne Snyder, his researcher at the New York Times and23 years his junior. After years of chaste but charged email exchanges on subjects such as Dorothy Day and St. Augustine, Snyder agreed to go on a date with Brooks in 2016. They married in 2017. And while The Second Mountain purports to describe the hyperindividualism of American politics and society as a disease and wonkily offers cures that fans of Oprah absorbed long ago, it would not be hyperbole to say that it is also, both explicitly and between the lines, a gushing paean to romance from a gobsmacked man happily rediscovering sex. As such, it is full of cringeworthy aphorisms. “Love,” writes Brooks, “plows open the hard crust of our personality and exposes the fertile soil below.”

Brooks won’t talk about what went down between him and his ex-wife, but he holds up his current romantic situation as a kind of standard: “There was a period when I was dating” — including a “deeply thoughtful” woman in New York — “and nothing felt like this. I can only report the truth. I am very definitely in love.”

The Second Mountain is a “wisdom” book that collects and reflects on fortune-cookie insights drawn from the Great White Male Thinkers (though he mentions a smattering of others, including yours truly on page 23), largely about the importance of self-sacrifice and community. “I think I have a bias — because I’m decent with words — toward glibness and shallowness, and I’ve tried to struggle against that through writing,” he tells me. “Like, to write my way to a better person.”

Brooks worries, a little, that his new book will be considered “woo-woo,” but he also knows that his base — the senior executives who hear him speak at the end of a three-day retreat on corporate health-care costs — will “eat it up more than any other audience. They have nobody in their lives who talks this way. I’m exaggerating, but the country is hungry for ‘How do you do relationship?’ ‘How do you lead a good life?’ ”

I ask Brooks whether he can see the irony: the pundit preaching on holiness, the public intellectual holding forth on humility, the middle-aged divorcé lecturing on love, the defender of the Republican aristocracy writing a book about the sacred poor. But self-knowledge has never been Brooks’s particular strength — or rather, in its mix of self-mocking, striving, and naïveté, his view of himself can fail to come into focus. “I don’t see myself as a privileged person,” he says, hesitating. “I make more than people — well, maybe I should take that back. Yeah, I do take that back.”

He works on the editorial page of the New York Times, I point out. “Yeah, but what is that? A lot of people work at the New York Times with a lot of different views. You work at New York Magazine.”

Brooks says he doesn’t read his negative press. In recent years, there has been quite a lot. The Never Trump League, of which he is a member, has evolved from a passionate Republican resistance movement to a small, ineffectual band of complainers. Critics on the left charge that Brooks’s professorial pose has turned tone-deaf. The more damning critique is that Brooks refuses to own up to his part in the current political crisis — that his defense of previous Republican administrations and Establishment ideals, and his continued support of conservatism in the tea-party era, contributed to the election of Trump himself. Since Brooks is at a moment of self-interrogation, the question presents itself. What does he think now of his boosterism of, say, George W. Bush?

“The question is, how boosterish was I?” parries Brooks.

“You were pretty boosterish.”

“I supported the war, which was obviously the biggest judgment error of my career,” he concedes. And now that he’s thinking back on it, he’d like to mention other regrets. In 2008, when Sarah Palin was John McCain’s running mate, “I called her a cancer. I should not have called a person a cancer.” Anything else? “There was a column I wrote about weed.”

What about his years of antagonism toward Barack Obama? “There are certainly things I got wrong,” Brooks answers. “I opposed the Detroit bailout. It was a clear win. That was good policy. In retrospect, everything is better if Trump is your vantage point.” Here Brooks displays his infamous elasticity, reminding me that at the start of the 2016 primary race, he wrote a mournful column called “I Miss Barack Obama.” “I certainly do,” he says now. “What’s happened to the Republican Party is cataclysmic.” And though he’s watching the large Democratic field with fascination, he’s not up to making prognostications. So far, the technocrat Cory Booker appeals. “I like Biden, but apparently I’m not allowed to do that,” he says. “I think he’s a good man, a genuinely good man — and he touches me a lot, too.”

These are not exactly the views of someone who has been “radicalized,” but Brooks presses on. What he really wants to talk about is Weave, the nonprofit he started with his friends at the Aspen Institute, which shines a light on community builders far from the “inner rings”: the teachers and coaches and protectors of refugees and domestic-violence victims who are motivated to do their work by a sense of necessity, vocation, and love. Brooks has met hundreds of these community leaders on his travels — “23 states over the past year,” he says proudly — and heard so much fury at racial injustice he was moved to write a column supporting reparations for slavery, five years after Ta-Nehisi Coates.

“Maybe racial injustice is at the core of everything,” he says. “I’ve had that thought.”

“Would you say that you got woke?” I ask. “Woke?” he says. He looks surprised at the word. “I guess that is the dictionary definition.” He puts up little air quotes with his fingers. “David Brooks Gets Woke,” he says. Then he laughs a little.