“I want to tell you something, and it’s going to make you mad.” It was my mother on the line. Moments before, I had been cheerfully ensconced in my sunny cubicle at the Wall Street Journal, where I worked as a reporter, but the sight of my childhood number flashing on the screen caused — as it always did when my mother called — a moment of pulse-quickening indecision. Answer it. Don’t answer it. Answer it. Decades of experience assured me that this conversation, in all likelihood, would go badly. And yet. At 36, I continued to hope for a happy ending.

“If it’s going to make me mad, then why even say it?” I responded, trying to keep my tone neutral.

Mom powered ahead. She had been to her hairdresser that morning, she told me. The two of them had gotten to talking. They had decided that it might be time to lighten my hair a shade or two, to something closer to blonde. And while I was at it (here was the real message), I might want to think about getting rid of the skunk stripe of gray hair that had characterized my “look” for the past five years. Her exact words escape me now, but the implication was clear. At the time, I was extremely single, a condition that had become nearly intolerable to her. Together with her hairdresser, my mother had finally uncovered the reason for my failure to wed, mate, and produce for her a grandbaby or two. No right-thinking man wanted a wife with weird hair. Luckily, there was an easy fix to my sad plight: ash blonde, with lowlights.

My mother and I were fundamentally very different. Her disapproval of my hair, a long-standing conflict between us, was merely a proxy, I felt, for her disapproval of me. My mother was graceful, old-fashioned, feminine. She had married at 24, had her first baby (me) at 25, and proceeded to follow my father, the doctor, around the country, sending him off to the hospital each day with a packed gourmet lunch.

I, on the other hand, was messy. Striving and ambitious and perpetually heartbroken. I came home from college cursing and smoking, hell-bent on establishing my independence. So I scoffed, uncharitably, at the more domestic path she had chosen. My mother’s hair was short and chic, like Audrey Hepburn or Shirley MacLaine. Mine was long and wild, snarled in childhood and spotted with paint or bubblegum, tied up in later years with shreds of an old T-shirt.

“Do you have to wear that rag on your head?” she would ask. “Do you think if you bug me about it enough I’ll actually stop?” I’d respond.

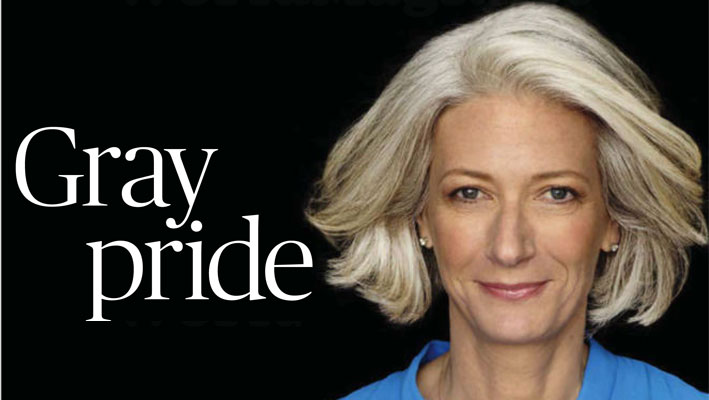

Unspoken between us was this undeniable fact: We had the same hair. Brunettes from birth, we started to gray in our 20s. By 30, the tinsel-like threads were abundant enough to be called “striking”; by 35, the right descriptors for our hair could be found among the metals and ores: pewter, silver, platinum, steel. Our hair — if I do say so myself — grayed beautifully, retaining a silky, glossy texture. My mother chose not to dye hers. She wore her silver hair with a shrug, like a pair of satin shoes with the heels worn down, the sign of a woman so beautiful she could afford to be careless about it. I have many memories of her, returning home from the grocery store or dinner out with my father, hooting with glee as she recounted the unexpected (but expected, somehow) compliment. “I was standing in line at the check-out and some woman behind me asked me for the name of my colorist. Ha!”

We tacitly agreed on one thing: My mother could afford to be gray at 30, whereas I could not. At 30, she was safely married with children. I, on the other hand, was still on the market, a cruel and intolerant place. This point came home to me during a blind date when I was 31 or so. We were watching the sun set over the Hudson River when the man sipping wine across the table from me guessed my age to be 37. I immediately called my hairstylist, a longtime friend, and she mixed for me a batch of deep-auburn-colored dye.

I expressed my ambivalence about this capitulation by refusing to color my hair completely. My hairdresser would always leave a portion, a streak, of my hair undyed. This would allow us to track the progress of the graying, and, like a well-placed tattoo, it would give me some versatility in my “look.” On late nights out, I could be a hipster, revealing the gray streak in my side-parted hair like Susan Sontag or Morticia Addams. At work, or on blind dates, I could deploy a center part and thus keep it under wraps, looking for all the world like a nice Jewish girl with a good job. I flipped my hair back and forth — stripe, no stripe — which attracted attention, and a fair amount of interest. In this way, I was like my mother. I was the girl with the remarked-upon hair. That day at the office, I hung up on my mother in a hot white rage, jumped up from my seat, and cruised the news- room seeking allies in my fury. How dare she dwell, shallowly, on the insufficiencies of my appearance. I was obviously doing well otherwise, with a great job, friends who loved me, steadiness, purpose. How could she let her anxiety about my love life occupy her so thoroughly that she would call me — at work, in the middle of the afternoon—to confront me with her darkest fear (which was also mine): that I would end up alone?

My coworkers were appropriately outraged, and together we cooked up a revenge plot. I would ask every male friend I knew to send my mother a postcard, telling her how gorgeous he found my hair. “Dear Mrs. Miller, I work with Lisa at the Journal, and I want you to know that I think her skunk stripe is very cool and sexy.” “Dear Mrs. Miller, I have never dated Lisa because I’m happily married, but I want you to know how awesome her hair is.” “Dear Mrs. Miller, Love Lisa’s hair.” Thus bombarded with male approval of me, she might finally shut up about my hair, and perhaps also relax a little bit about my attractiveness to the opposite sex.

The plan worked. My mother got a bunch of those postcards. She called me when each one arrived to read it aloud, laughing with delight. She stopped bugging me about my hair, she really did. Though her anxiety did not abate entirely, I like to think that my ploy helped her to rein it in, at least in my presence.

That all happened more than 10 years ago. At 38, I finally met a man who would love me even if I went bald, and on the day he proposed, I stopped my appointments with the colorist. For so it goes with mothers: As much as you resist them, their influence permeates you to your very core — and in my case, to every hair on my head. It’s obvious we both wanted the same thing, which was for me to be married, and a mother myself. But what I did not realize, and what I wish I could tell her now, is that all my rebellions (hair and otherwise) masked a deeper yearning, which was to have her kind of beauty — the natural and incontrovertibly feminine kind. Because of my mother, the confidence to wear a full head of gray hair is, to me, the mark of true beauty.

My mother died two years ago, but not before she walked me down the aisle, and not before she called me (repeatedly) in the labor and delivery room to ask how it was going, and not before she grew to know my daughter and adore in her all the sass and independence that infuriated her in me. Now she is gone and I am the one walking around in the world with hair that sets me apart from the other moms in the school yard and with a child who has to use the silver crayon in the Crayola box to draw pictures of her family. And when people stop me on the street to compliment my hair, this is what I always say: “Thank you. I got it from my mother.”