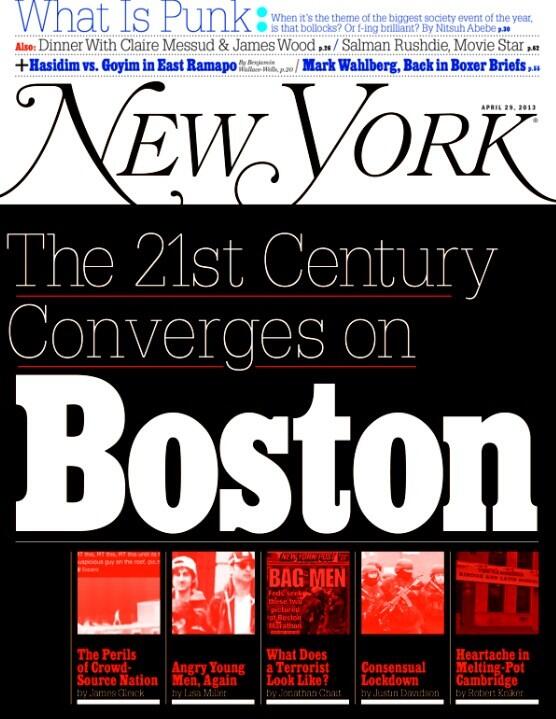

The older one looks like some kind of loser, a boxing maniac with a love for trashy Euro style. But Dzhokhar, the younger brother, well, he seems like a sweetie pie, with those moony eyes and that fuzzy halo of hair. Robin Young, a radio personality in Boston, threw a prom party in her backyard for her nephew, and Dzhokhar, a classmate, was there. He was “the light of the party,” she remembered on air. “A beautiful, beautiful boy.”

Which just goes to show that evil may not have a single face, but it can be reliably found within one kind of body: that of an angry man in his late teens or twenties. Three days before they killed twelve classmates, one teacher, and themselves at their Colorado high school in 1999, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris partied on prom night, looking outwardly “like normal young boys about to graduate,” Dave Cullen wrote in his 2009 book Columbine. “They were testing authority, testing their sexual prowess—a little frustrated with the dumbasses they had to deal with, a little full of themselves.” Adam Lanza, Timothy McVeigh, Jared Lee Loughner, James Eagan Holmes, Seung-Hui Cho—some of these villains were afflicted with mental illness, some of them drawn to extremist ideologies. It was easy to distance ourselves from each of them with a variety of alienating labels: autistic gun nut, domestic terrorist, sociopath, embittered immigrant loser. But they have three things indisputably in common. Their gender. Their youth. And a willingness to hate, which forensic psychiatrist Michael Welner distinguishes from simple anger. “You have to be hateful of everyone to kill anyone,” he says. “A person who will undertake a spectacle crime or a mass killing, that is one of the defining qualities: They don’t care that anyone can be killed.”

Angry. Young. Men. The description doesn’t explain the motivations behind every notorious bloodbath, but it’s a place to start—perhaps the only place to start. Men have testosterone, an aggression drug, coursing through their veins; levels rise under stress, and young men have more of it than older ones. (Give testosterone to female rats, and they will become uncharacteristically violent.) Moral development isn’t complete in humans until about age 21—“This is why we don’t put the 14-year-olds in charge,” says Sam Harris, a neuroscientist and moral philosopher. And men are likelier than women to act out vengeance, partly because their brains do not propel them to seek help, to pick up the phone or see a shrink, when enraged. And that male proclivity to assert power through violence has been true for males, and not for females, for millions of years, which is why when you give your 4-year-old daughter a toy sword to play with, she may just turn it into a fairy wand and go on with her day.

The willingness of men to imagine themselves as warriors is rooted in a protective impulse that can get distorted through culture and especially trauma, says family therapist Michael Gurian, and the resulting mental illnesses caused by trauma too often go untreated in men. These criminals have broken selves, says Gurian, and their culture abets their appetite for violence. The terrorist or the mass murderer believes, because his white-supremacist or Islamist or boxing world tells him so, that he can fill his emptiness with a sensationally violent act. “These crimes are very much about the evolution of masculine identity,” says Welner. Gurian explains the mind-set like this: “I develop a self by destroying. I will now go destroy. That will hopefully create in me enough of a self that I will have some power. I will have some status. I will show people.”

But what do they show? All these murderous men have something they want to prove: a devotion to Allah, a fuck-you to the world, a dexterity with explosives, a political objection or a nationalist passion. But the more of them we meet, the less they seem to be fringe ideological actors and more like various avatars of a single type. Dzhokhar, so far, is a puzzle. A look at the horrifying and banal Twitter feed reported to be his shows a boy who liked Breaking Bad and followed college basketball, listened to Eminem and Dr. Dre and knew a song from Rent, who was passingly familiar with the works of the political theorist Edmund Burke. “Dzhokhar is a sweet boy, innocent. He was always smiling, friendly, and happy,” a man describing himself as a cousin told the Boston Globe last week. “I don’t know how he is involved in this.” The boy who spent hours Friday night hiding in a boat in Watertown could have been one of the charming 19-year-olds at your last backyard party.